Tracklist

Bible - Old Testament - Lyricist

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Boer, Michele de (soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Mahon, Peter (counter-tenor)

Tomkins, Giles (bass-baritone)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Krause, Anita (mezzo-soprano)

Brown, Nils (tenor)

Aradia Chorus (Choir)

Aradia Ensemble (Ensemble)

Mallon, Kevin (Conductor)

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s parents stood squarely in the German professional middle class, whose values permeated the lives of the family members: his father, a classical scholar, was the principal of a secondary school and his mother was a teacher. His grandmother on his father’s side was a member of the von Dieskau family, for one of whom J.S. Bach had written his Peasant Cantata of 1742. Initially Fischer-Dieskau studied piano, both with his mother and while at school; but having also sung as a child, at sixteen he commenced formal vocal study in Berlin with Professor Georg Walter.

In 1943, after completing one semester at the Berlin Conservatory, Fischer-Dieskau joined the Wehrmacht; but after capture by the Allies in Italy spent two years as an American prisoner of war, during which he would often sing to his fellow prisoners. He returned to Berlin in 1947, studied briefly with Professor Hermann Weissenborn at the Conservatory, and soon was singing professionally. As he has commented about this period, ‘I passed my final exam in the concert hall.’

His first major professional engagement was in 1947 as a last-minute substitute for another singer in a performance at Badenweiler, given without rehearsal, of Brahms’s Ein Deutsches Requiem. In the autumn of that year Fischer-Dieskau gave his first lieder recital in Leipzig, soon followed by his first, very successful, Berlin concert at the Titania Palast. During the following year he broadcast Schubert’s Winterreise on Berlin radio and joined the Städtische Oper (Municipal Opera) in Berlin as a principal lyric baritone, making his debut in the autumn of 1948 as Posa / Don Carlo, with Ferenc Fricsay conducting. This company, which became the Deutsche Oper in 1961, was to be his artistic home until his retirement from opera in 1978.

Fischer-Dieskau quickly made his mark internationally, appearing as a guest at the Bavarian State Opera, Munich, the Hamburg State Opera and the Vienna State Opera, and from 1949 undertaking concert tours across France, Italy, Holland and Switzerland. He first appeared at the Salzburg Festival in 1951, singing Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden gesellen with Furtwängler conducting, and returned regularly from 1956 until 1973, appearing as the Count / Le nozze di Figaro (1960–1964), Verdi’s Macbeth (1965), and Don Alfonso / Così fan tutte (1972–1973) as well as giving numerous song recitals. Also in 1951 he made his London debut at the Royal Albert Hall, singing in Delius’s A Mass of Life with Sir Thomas Beecham conducting. Fischer-Dieskau returned to the UK frequently: highlights included the first performances of Britten’s War Requiem (1962, Coventry Cathedral) and his Songs and Proverbs of William Blake (composed for the singer) (1965, Aldeburgh Festival); and two notable appearances at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden: as Mandryka / Arabella, with Georg Solti conducting (1965) and as Verdi’s Falstaff (1967). His debut at the Bayreuth Festival came in 1954 with Wolfram / Tannhäuser (1954–1955, 1961) and the Herald / Lohengrin (1954), followed by Amfortas / Parsifal (1955–1956) and Kothner / Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1956). His first concert tour of the United States was in 1955, singing both in concert and in lieder recitals, including a complete Winterreise without intermission in New York accompanied by Gerald Moore.

In opera, Fischer-Dieskau’s repertoire was extensive. It included, in addition to the roles already mentioned, Jochanaan (Salome, 1952), Don Giovanni (1953), Busoni’s Faust (1955), Renato / Un ballo in maschera (1957), Hindemith’s Mathis (1959), Wozzeck (1960), Eugene Onegin (1961), Barak / Die Frau ohne Schatten (1963), Sachs / Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1975) and the title role in the premiere of Reimann’s Lear (1978). On record his roles included both Olivier and the Count in different recordings of Capriccio, Papageno / Die Zauberflöte (Böhm), Kurwenal / Tristan und Isolde (Furtwängler), the Dutchman (Konwitschny), Wotan / Das Rheingold (Karajan) and Rigoletto (Kublelík). An ardent advocate of contemporary music, Fischer-Dieskau performed works by many living composers including Samuel Barber, Hans Werner Henze, Karl Amadeus Hartmann, Ernst Krenek, Witold Lutosławski, Siegfried Matthus, Gottfried von Einem and Winfried Zillig. He made a vast number of recordings, especially of lieder, committing to disc virtually the entire repertoire of German Romantic songs appropriate for a male singer by Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Brahms, Loewe, Richard Strauss and Wolf.

Having retired from opera in 1978, Fischer-Dieskau made his last public appearance as a singer aged sixty-seven in a gala concert on New Year’s Eve 1992 at the Bavarian State Opera. Subsequently he devoted himself to teaching, painting and writing books. Possessed of a beautiful natural voice, Fischer-Dieskau also had the consummate ability to communicate meaning through vocal inflection, posture, gesture, facial expression and eye contact, making him one of the most complete singers of the twentieth century. In an interview with the English journalist Martin Kettle, Fischer-Dieskau revealed that the greatest influence upon him was the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler: ‘He once said to me that the most important thing for a performing artist was to build up a community of love for the music with the audience, to create one fellow feeling among so many people who have come from so many different places and feelings. I have lived with that ideal all my life as a performer.’

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Singers, Naxos 8.558097-100).

Maurizio Pollini’s parents were both artistically inclined. His mother was a singer, whilst his father Gino Pollini not only played the violin, but was in the forefront of contemporary architectural design in Italy. Pollini’s early studies were with Carlo Lonati and then with Carlo Vidusso at the Milan Conservatory from the age of thirteen. At fourteen, Pollini played the complete Chopin études in public, and when he was fifteen he won second prize at the Geneva International Piano Competition in a year where no first prize was awarded. Two years later he won the Ettore Pozzoli International Piano Competition and in 1960 won the prestigious International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw. However, at eighteen years old he was not fully equipped to take on a huge workload of concerts, nor did he want to become known only as a Chopin player. A planned tour of America was cancelled, and his advertised London debut was twice postponed. It is not true however, as some sources state, that Pollini practically retired from public life for almost seven years, reappearing in 1968; in fact he made his London debut in April 1963 (when he did not receive good reviews for his rushed performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the London Symphony Orchestra and Colin Davis). The critic of The Times noted that ‘…his only concern seemed to be getting the notes over and done with as soon as possible.’

Pollini took a few lessons from Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli in 1961, but also acknowledges pianists of his youth including Wilhelm Backhaus, Clara Haskil, Edwin Fischer, Alfred Cortot and Arthur Rubinstein. When he did resume touring in 1968 he was a finished artist who took his place at the forefront of the world’s great pianists, playing and touring in Britain, Europe, America and Japan.

Pollini became an advocate of contemporary music and performed works by Schoenberg and Webern as well as Stockhausen, Nono, Manzoni and Sciarrino. His analytical approach to music is ideal for these works, but for the more Romantic repertoire, Pollini has been accused, more so now than at the beginning of his career, of a coldness and aloofness in his interpretations. In 1984 Nicholas Kenyon asked why at times Pollini’s playing sounded ‘blank, rather clamourous and uninvolved’. In January 2000 Tim Parry began his review of Pollini’s disc of Chopin’s ballades with the words, ‘Wherever you stand on the “great Pollini debate”…’, whilst Michael Glover in 1998 wrote of his dislike of Pollini in no uncertain terms. Referring to a recent recital at London’s Royal Festival Hall he wrote of ‘…the Italian’s faceless, four-square Chopin and pedestrian Debussy’. He describes Pollini’s playing as ‘…that of an artist who has internalised his music-making to such an extent that a nullifying block has arisen between the emotions he is experiencing whilst playing and any communication of these forces at the keyboard’.

However, Pollini has his admirers, and audiences are eager to hear his Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin and Debussy: all composers who feature prominently in his repertoire. Pollini also plays Schubert and Brahms and has an inherent sense of formal structure, where each work he performs is built on salient architectural lines. For all the controversy Pollini generates in the press and amongst record collectors, he is not an artist of wayward intentions; his style may have changed over the years, but Pollini can still be classed as one of the great pianists of his era.

Pollini recorded his prize-winning performance of Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor Op. 11 in 1960 for EMI in London. It is still one of the best recordings of this work. In 1968 he recorded some solo works of Chopin for EMI in Paris, but from 1971 Pollini has recorded exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. His output over the past thirty years has not been a large one, yet it covers the major areas of his repertoire. Some of his recordings have attained almost legendary status, such as Stravinsky’s Three Movements from Petrushka, Boulez’s Piano Sonata No. 2, Prokofiev’s Piano Sonata No. 7 Op. 83 and Chopin’s twenty-four études. In these recordings Pollini’s superb technique gets ample display, and live performances of the same works have had just as much adrenalin, excitement and accuracy. Excellent recordings of Chopin from the mid-1970s include a selection of the polonaises and a disc of the twenty-four Préludes Op. 28.

Pollini has recorded core repertoire including Schubert’s ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy D. 760 and Piano Sonata in B flat D. 960, Schumann’s Fantasie Op. 17, Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor, and the last five of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. He has recorded both Brahms’s piano concertos, Bartók’s Piano Concertos Nos 1 and 2 and Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto, as well as all five of Beethoven’s concertos twice, the second time with Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. His important interpretations of contemporary music include recordings of Boulez’s Piano Sonata No. 2, a disc of works by Luigi Nono, and the complete piano music of Arnold Schoenberg. Recent recordings of Chopin’s ballades and scherzos and Debussy’s préludes have received mixed reviews. Bryce Morrison thought that Pollini had ‘…lost contact with the central qualities of Debussy’s sound world’. Although he performed the first book of Bach’s Das wohltemperierte Klavier in public during Bach’s tercentenary year, so far Pollini has not recorded it, but he is continuing a long-term project to record the complete Beethoven piano sonatas.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).

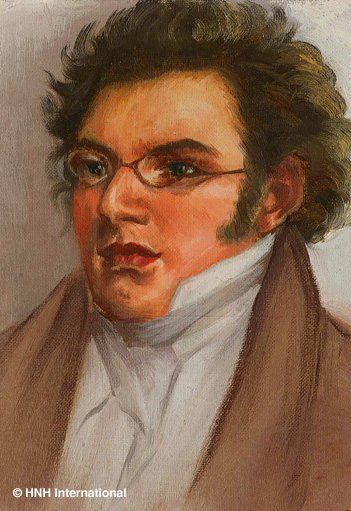

The son of a schoolmaster who had settled in Vienna, Franz Schubert was educated as a chorister of the imperial court chapel. He later qualified as a schoolteacher, briefly and thereafter intermittently joining his father in the classroom. He spent his life largely in Vienna, enjoying the company of friends but never holding any position in the musical establishment or attracting the kind of patronage that Beethoven had 20 years earlier. His final years were clouded by illness as the result of a syphilitic infection, and he died aged 31, leaving much unfinished. His gifts had been most notably expressed in song, his talent for melody always evident in his other compositions. Schubert’s compositions are generally numbered according to the Deutsch catalogue, with the letter D.

Stage Works

Schubert wrote operas, Singspiel and incidental music for the theatre. His best-known compositions of this kind include the music for the unsuccessful play Rosamunde, Fürstin von Zypern (‘Rosamunde, Princess of Cyprus’), mounted at the Theater an der Wien in December 1823. The ballet music and entracte from Rosamunde are particularly well-known.

Church Music

Among the various works Schubert wrote for church use, particular mention may be made of the second of his six complete settings of the Mass. He completed his final setting of the Mass in the last year of his life, and it was first performed the following year.

Choral and Vocal Music

Schubert wrote for mixed voices, male voices and female voices, but by far the most famous of his vocal compositions are the 500 or so songs—settings of verses ranging from Shakespeare to his friends and contemporaries. His song cycles published in his lifetime are Die schöne Müllerin (‘The Fair Maid of the Mill’) and Die Winterreise (‘The Winter Journey’), while Schwanengesang (‘Swan Song’) was compiled by a publisher after the composer’s early death. Many songs by Schubert are very familiar, including ‘Der Erlkönig’(‘The Erlking’), the ‘Mignon’songs from Goethe and the seven songs based on The Lady of the Lake by Sir Walter Scott.

Orchestral Music

The ‘Unfinished’ Symphony of Schubert was written in 1822, but no complete addition was made to the two movements of the work. Other symphonies of the eight more or less completed include the ‘Great’ C major Symphony and the Classical and charming Fifth Symphony. His various overtures include two ‘in the Italian style’.

Chamber Music

Of Schubert’s various string quartets the Quartet in A minor, with its variations on the well-known Rosamunde theme and the Quartet in D minor ‘Death and the Maiden’, with variations on the song of that name, are the most familiar. The Piano Quintet, ‘Die Forelle’ (‘The Trout’), includes a movement of variations on that song, while the great C major String Quintet of 1828 is of unsurpassable beauty. The two piano trios and the single-movement Notturno date from the same year. Schubert’s Octet for clarinet, horn, bassoon, two violins, viola, cello and double bass was written early in 1824. To the violin sonatas (sonatinas) of 1816 may be added the more ambitious ‘Duo’ Sonata for violin and piano, D. 574, of the following year and the Fantasy, D. 934, published in 1828, the year of Schubert’s death. The ‘Arpeggione’ Sonata was written for a newly devised and soon obsolete stringed instrument, the arpeggione. It now provides additional repertoire for the cello or viola.

Piano Music

Schubert’s compositions for piano include a number of sonatas, some left unfinished, as well as the Wanderer Fantasy and two sets of impromptus, D. 899 and D. 935. He also wrote a number of dances for piano—waltzes, Ländler and German dances. His music for piano duet includes a Divertissement à l’hongroise, marches and polonaises largely written for daughters of a member of the Esterházy family, for whom he was for a time employed as a private teacher.