|

Oops! Something went wrong!

The application has encountered an unhandled error.

Our technical staff have been automatically notified and will be looking into this with the utmost urgency.

|

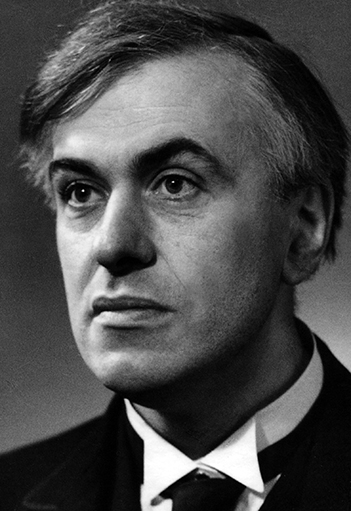

Eduard Erdmann was the youngest of four brothers and began his piano lessons at around the age of eight. A year later Erdmann’s father, who was a lawyer, moved the family to Riga and in 1912 Erdmann began to study with Bror Möllesten, a pupil of Leschetizky. He then had lessons from Jean du Chastain and also received tuition in theory and harmony from the organist of Riga cathedral, Harald Creutzberg. The following year Erdmann’s father died, and his mother moved to Berlin where Eduard studied composition with Heinz Tiessen and piano with Liszt pupil Conrad Ansorge at summer master-classes in Koenigsberg, later becoming a full-time pupil. Erdmann made his debut in Berlin at one of Hermann Scherchen’s ‘Evenings of Contemporary Music’. He played Sechs kleine Klavierstücke Op. 19 by Schoenberg, the Piano Sonata Op. 1 by Alban Berg and his own Klavierstücke Op. 6. In Berlin Erdmann met and was invited to the homes of many prominent musicians including Arthur Nikisch, Ferruccio Busoni, Richard Strauss and Artur Schnabel whose compositions Erdmann championed, giving the first performance of Schnabel’s Piano Sonata. Almost from the first, Erdmann was taken seriously as pianist and composer and from 1921 to 1923 he took part in the Donaueschingen Festival of contemporary chamber music as a member of the jury.

In the early 1920s Erdmann made tours of Scandinavia and Spain and in 1925 was invited by conductor Hermann Abendroth to teach a piano master-class at the Cologne Conservatory. In December 1926 Erdmann played for the opening of the Bauhaus in Dessau and three years later began giving concerts with Walter Gieseking on two pianos, something they did for the next twenty years. In 1929 Otto Klemperer conducted the first performance of Erdmann’s Piano Concerto with its composer as soloist, and in April 1934 Erdmann appeared at London’s Wigmore Hall with violinist Alma Moodie. Moodie, an Australian musician and pupil of Carl Flesch who lived in Berlin, had played Busoni’s Violin Concerto at a Philharmonic Concert in London and now played his Violin Sonata in E minor with Erdmann. The two appeared regularly together from 1920 until Moodie’s death in 1943. In the same programme Erdmann played Bach’s ‘Goldberg’ Variations BWV 988, which was found to be ‘…a little disappointing when compared with his sensitive performance of Busoni and the ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata.’ From the outset, the critic of The Times did grant that Erdmann was ‘a pianist of the finest musical intelligence’. Erdmann was a champion of Busoni’s music and played both the mighty Piano Concerto Op. 39 and the Fantasia contrappuntistica in public.

Erdmann had been performing more abroad from 1936, but as a composer had to play down his image because his compositions were classed as ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis; hence his public activity as a composer was not visible from 1933 to 1945. He also resigned from the Cologne Conservatory when he witnessed Jewish colleagues being attacked by the Nazis. By the time World War II was over, Erdmann’s compositions already seemed dated, so he had to earn his living as a pianist. He retreated to his home at Langballigau, a house that he had purchased in 1923 near the Flensburg Bay not far from the Danish border, and lived there for the rest of his life.

After the war, when Erdmann gave his first concert in Germany, he played four evenings of works by Krenek, Hindemith, Berg and Schoenberg, composers who had been banned by the Nazis. Although he was offered faculty posts in Munich and Berlin, Erdmann declined; however, when asked by his friend Philip Jarnach to give master-classes at Hamburg Conservatory, he agreed. During the late 1940s and early 1950s Erdmann again played more public concerts, but in 1954 suffered his first heart attack. In June 1958 he gave his last concert (in honour of Clara Haskil), and died later that month from another heart attack.

Erdmann has been called ‘the pianist-philosopher’. He was a cultured man who read voraciously; his library was renowned and he had professional and personal relationships with many artists, scientists, writers and, among musicians, Artur Schnabel, Paul Hindemith and Ernst Krenek. Apparently, Erdmann even memorised Dante’s La divina commedia in Italian. He approached piano playing as a science and was analytical to the point of being pedantic in his interpretations. In fact, he did not believe in the artist’s personality being manifest; not a trace of his personality must enter into his performance. He attempted to strip away everything except the music of the composer. Never a Romantic player, Erdmann reveals everything from a studied point of view, delivered in a fashion as objectively as possible. As eclectic as he was in his reading, so he was in his choice of composers. He liked to juxtapose composers such as Bach and Mussorgsky, Schubert and Krenek, or Beethoven and Busoni. His repertoire was wide, and in Berlin between 1919 and 1925 he played, along with works by many then more famous composers, music by Froberger, Kuhnau, Alkan, Smetana, Rachmaninov, Nielsen, Scriabin, Bartók, Schnabel and Jarnach. With Schnabel, Erdmann was one of the few pianists to play the piano sonatas by Schubert from the 1920s onwards. Towards the end of his life he played these sonatas regularly and became associated particularly with Schubert’s last few great works in this form.

In 1928 Erdmann recorded for Polydor in Berlin. All the titles he recorded are of twentieth-century music and include works by Krenek, Smetana, Debussy, Tiessen and Erdmann himself. On 6 September 1935 he performed Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor Op. 37 with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Henry Wood at London’s Queen’s Hall. The following day he recorded some short works by Beethoven and Brahms for Parlophone in London, and when he returned to Berlin recorded the same Beethoven concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and Artur Rother on 17 November 1935. It is a fine performance displaying Erdmann’s solid and unsentimental playing. More recordings were made for Polydor in Berlin in November 1940 including Haydn’s Variations in F minor and Schubert’s twelve German Dances D. 790: many of these 78s have been reissued on two compact discs by the German company Bayer. A large number of Erdmann’s radio broadcasts have survived in German radio archives, and performances from the 1950s of the last great sonatas by Schubert have been issued. Also in the late 1950s EMI Electrola issued some of this material on LP including Schumann’s Fantasiestücke Op. 12 and Schubert’s Impromptus D. 899. Since 1996 the French label Tahra has issued three two-disc sets of Erdmann. The first includes the Beethoven concerto from 1935 already mentioned, as well as broadcasts of a Handel suite, an excellently compelling version of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Debussy’s Fantaisie for piano and orchestra and Schumann’s Konzertstück Op. 92. Volume two contains the last four of Schubert’s piano sonatas, whist the third volume contains different recordings of the same Beethoven concerto, some Mozart, and the last two Schubert sonatas as well as Liszt’s Valse oubliée and Mephisto Polka. It is thanks to this material being issued that it is possible to assess Erdmann’s art by having a much broader view of his work.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).

Reger enjoys a particularly high reputation among organists, to whose repertoire he made important additions. Born in Bavaria, he was a pupil of the important theorist Hugo Riemann and taught at the University of Leipzig before his appointment as conductor of the Meiningen Court Orchestra in 1911. In addition to his activities as a teacher, conductor and composer, he was also a pianist and organist.

Orchestral Music

Among a variety of orchestral works, including a Piano Concerto and a Violin Concerto, Reger’s Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Mozart, an arrangement of his work of the same title for two pianos, shows, typically, a resourceful and sometimes complex use of the theme on which it is based.

Chamber Music

Reger wrote a considerable amount of chamber music of all kinds, including a number of violin sonatas and other duo sonatas, as well as string quartets and works for other groups of players. While of interest, nothing of this has become a part of popular repertoire, either for players or audiences.

Vocal and Choral Music

Among choral compositions by Reger the eight Geistliche Gesänge (‘Spiritual Songs’), Op. 138 have proved particularly moving. Once again, however, his choral works and songs have failed to achieve any significant position in performing repertoire.

Piano Music

Reger wrote a number of short piano pieces. His Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Mozart, Op. 132a for two pianos, is probably the best known of his compositions for piano. Other sets of variations include Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Beethoven, Op. 86 for two pianos, and Variations and Fugue on a Theme of J.S. Bach, Op. 81 and Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Telemann, Op. 134 for one piano.

Organ Music

Reger’s organ music offers a considerable challenge to performers and some works are said to have been composed as just such a challenge to his friend, the organist Karl Straube. Notable organ works include chorale fantasias on Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott and other Lutheran chorale tunes. His compositions for organ include a Fantasia and Fugue on B-A-C-H.

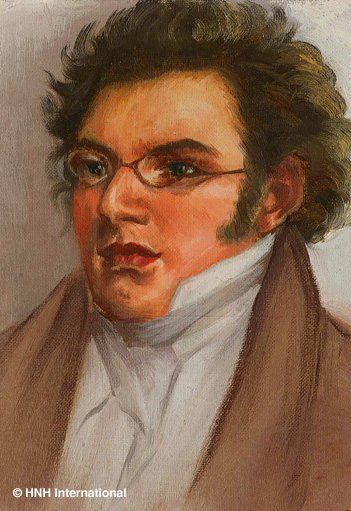

The son of a schoolmaster who had settled in Vienna, Franz Schubert was educated as a chorister of the imperial court chapel. He later qualified as a schoolteacher, briefly and thereafter intermittently joining his father in the classroom. He spent his life largely in Vienna, enjoying the company of friends but never holding any position in the musical establishment or attracting the kind of patronage that Beethoven had 20 years earlier. His final years were clouded by illness as the result of a syphilitic infection, and he died aged 31, leaving much unfinished. His gifts had been most notably expressed in song, his talent for melody always evident in his other compositions. Schubert’s compositions are generally numbered according to the Deutsch catalogue, with the letter D.

Stage Works

Schubert wrote operas, Singspiel and incidental music for the theatre. His best-known compositions of this kind include the music for the unsuccessful play Rosamunde, Fürstin von Zypern (‘Rosamunde, Princess of Cyprus’), mounted at the Theater an der Wien in December 1823. The ballet music and entracte from Rosamunde are particularly well-known.

Church Music

Among the various works Schubert wrote for church use, particular mention may be made of the second of his six complete settings of the Mass. He completed his final setting of the Mass in the last year of his life, and it was first performed the following year.

Choral and Vocal Music

Schubert wrote for mixed voices, male voices and female voices, but by far the most famous of his vocal compositions are the 500 or so songs—settings of verses ranging from Shakespeare to his friends and contemporaries. His song cycles published in his lifetime are Die schöne Müllerin (‘The Fair Maid of the Mill’) and Die Winterreise (‘The Winter Journey’), while Schwanengesang (‘Swan Song’) was compiled by a publisher after the composer’s early death. Many songs by Schubert are very familiar, including ‘Der Erlkönig’(‘The Erlking’), the ‘Mignon’songs from Goethe and the seven songs based on The Lady of the Lake by Sir Walter Scott.

Orchestral Music

The ‘Unfinished’ Symphony of Schubert was written in 1822, but no complete addition was made to the two movements of the work. Other symphonies of the eight more or less completed include the ‘Great’ C major Symphony and the Classical and charming Fifth Symphony. His various overtures include two ‘in the Italian style’.

Chamber Music

Of Schubert’s various string quartets the Quartet in A minor, with its variations on the well-known Rosamunde theme and the Quartet in D minor ‘Death and the Maiden’, with variations on the song of that name, are the most familiar. The Piano Quintet, ‘Die Forelle’ (‘The Trout’), includes a movement of variations on that song, while the great C major String Quintet of 1828 is of unsurpassable beauty. The two piano trios and the single-movement Notturno date from the same year. Schubert’s Octet for clarinet, horn, bassoon, two violins, viola, cello and double bass was written early in 1824. To the violin sonatas (sonatinas) of 1816 may be added the more ambitious ‘Duo’ Sonata for violin and piano, D. 574, of the following year and the Fantasy, D. 934, published in 1828, the year of Schubert’s death. The ‘Arpeggione’ Sonata was written for a newly devised and soon obsolete stringed instrument, the arpeggione. It now provides additional repertoire for the cello or viola.

Piano Music

Schubert’s compositions for piano include a number of sonatas, some left unfinished, as well as the Wanderer Fantasy and two sets of impromptus, D. 899 and D. 935. He also wrote a number of dances for piano—waltzes, Ländler and German dances. His music for piano duet includes a Divertissement à l’hongroise, marches and polonaises largely written for daughters of a member of the Esterházy family, for whom he was for a time employed as a private teacher.

The son of a bookseller, publisher and writer, Robert Schumann showed early abilities in both music and literature, the second facility used in his later writing on musical subjects. After brief study at university, he was allowed by his widowed mother and guardian to undertake serious study of the piano with Friedrich Wieck, whose favourite daughter Clara was later to become Schumann’s wife. His ambitions as a pianist were thwarted by a weakness in the fingers of one hand, but the 1830s nevertheless brought a number of compositions for the instrument. The year of his marriage, 1840, was a year of song, followed by attempts in which his young wife encouraged him at more ambitious forms of orchestral composition. Settling first in Leipzig and then in Dresden, the Schumanns moved in 1850 to Düsseldorf, where Schumann had his first official appointment, as municipal director of music. In 1854 he had a serious mental breakdown, followed by two years in the asylum at Endenich before his death in 1856. As a composer Schumann’s gifts are clearly heard in his piano music and in his songs.

Orchestral Music

Symphonies

Schumann completed four symphonies, after earlier unsuccessful attempts at the form. The first, written soon after his marriage and completed early in 1841, is known as ‘Spring’ and has a suggested programme. His Second Symphony followed in 1846, and the Third Symphony, ‘Rhenish’, a celebration of the Rhineland and its great cathedral at Cologne, was written in Düsseldorf in 1850. Symphony No. 4 was in fact an earlier work, revised in 1851 and first performed in Düsseldorf in 1853. The Overture, Scherzo and Finale, Op. 52 was described by the composer as a ‘symphonette’.

Concertos

Schumann’s only completed piano concerto was started in 1841 and finished in 1845. The Cello Concerto of 1850 was first performed four years after Schumann’s death, while the 1853 Violin Concerto had to wait over 80 years before its first performance in 1937. The Konzertstück for four French horns is an interesting addition to orchestral repertoire, and his Introduction and Allegro for piano and orchestra was completed in 1853.

Overtures

Schumann’s only completed opera, Genoveva, was unsuccessful in the theatre, but its overture holds a place in concert-hall repertoire, along with an overture to Byron’s Manfred, again first intended for the theatre. Concert overtures include Die Braut von Messina (‘The Bride from Messina’), based on Schiller’s play of that name; Julius Cäsar, based on Shakespeare; and Hermann und Dorothea, based on Goethe. A setting of scenes from Goethe’s Faust also includes an overture.

Chamber Music

Schumann wrote three string quartets in 1842, a fertile period that also saw the composition of a piano quintet and a piano quartet. Other important chamber music by Schumann includes three piano trios, three violin sonatas, and a number of shorter character pieces that include the Märchenbilder for viola and piano, collections of Phantasiestücke with alternative instrumentation, the Fünf Stücke im Volkston for cello (or violin) and piano, and other short pieces generally suggesting a literary or otherwise extra-musical programme.

Choral and Vocal Music

Schumann wrote a number of part-songs for mixed voices, for women’s voices and for men’s voices, including four collections of Romanzen und Balladen and two of Romanzen for women’s voices. His choral works with orchestra include Scenes from Goethe’s Faust; Das Paradies und die Peri, based on Thomas Moore’s poem Lalla Rookh; and Requiem for Mignon, based on Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister. In his final years he wrote a Mass and a Requiem. The solo songs of Schumann offer a rich repertoire and are an important addition to the body of German Lieder. From these many settings mention may be made of the collections and song cycles Myrthen, Op. 25, Liederkreis, Op. 39, Frauenliebe und -leben, Op. 42, and Dichterliebe, Op. 48, all written in the ‘Year of Song’, 1840.

Piano Music

The piano music of Schumann, whether written for himself, for his wife, or, in later years, for his children, offers a wealth of material. From the earlier period comes Carnaval—a series of short musical scenes with motifs derived from the letters of the town of Asch; this was the home of a fellow student of Friedrich Wieck called Ernestine von Fricken, to whom Schumann was briefly engaged. The same period brought the Davidsbündlertänze (‘Dances of the League of David’), a reference to the imaginary league of friends of art against the surrounding Philistines. This decade also brought the first version of the monumental Symphonic Studies (based on a theme by the father of Ernestine von Fricken) and the well-known Kinderszenen (‘Scenes of Childhood’). Kreisleriana has its literary source in the Hoffmann character Kapellmeister Kreisler, Papillons (‘Butterflies’) has a source in the work of the writer Jean Paul, and Noveletten has a clear literary reference in the very title. Later piano music by Schumann includes the Album für die Jugend (‘Album for the Young’) of 1848, Waldszenen (‘Forest Scenes’) of 1849, and the collected Bunte Blätter (‘Coloured Leaves’) and Albumblätter (‘Album Leaves’) drawn from earlier work.