Serkin’s father moved his family of eight children from Bohemia to Vienna in order that his talented son could gain a musical education. At the age of nine Serkin played for Alfred Grünfeld who suggested that young Rudolf should study with Richard Robert. Serkin made his Vienna debut at the age of twelve playing Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto in G minor Op. 25, a work he would play throughout his career, but his father forbade any concert tours and saw that his son continued studying with Robert and also with Joseph Marx and Arnold Schoenberg for composition.

At the end of his period of study with Robert, Serkin played for Ferruccio Busoni, whose opinion was that Serkin was too old to study with him and should rather play as many concerts as possible. It was in this same year of 1920 that Serkin met violinist Adolf Busch. Although Serkin was only seventeen, Busch asked him to accompany his chamber group on tour and meanwhile invited Serkin to live with his family. From this time onward the lives of the two musicians were intertwined, Serkin living with the Busch family and eventually marrying Busch’s daughter Irene in 1935. During the 1920s Serkin played recitals both solo and in partnership with Busch, gave concerts with the Busch Chamber Players and at his Berlin debut played Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5. The duo was unusual for its time in that both players were equals on the concert platform, not a star violinist with his accompanist. In 1933 Serkin played for the first time in America at a concert in Washington with Busch, and by 1936 was prominent enough to make his Carnegie Hall debut with Arturo Toscanini. He played two works, Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 Op. 58 and K. 595 in B flat by Mozart.

In 1939 Serkin and the Busch family moved to America to escape the Nazis even though they had already been living in Basle, Switzerland. Not long after he arrived in America, Serkin was asked to join the staff of the Curtis Institute of Music where he taught until 1975. It was in 1949 that the germ of an idea took shape as the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont. Busch was asked to organise a summer programme of chamber music at Marlboro College. In 1950 Busch got together a group of his musician friends: his cellist brother Hermann, Serkin, flautist Marcel Moyse, Moyse’s son Louis (a pianist), and his daughter-in-law Blanche (née Honegger), a violinist. Together they began an annual summer event of study groups and workshops for talented students. When Adolf Busch died in 1952, Serkin took over the helm until it was in turn passed to Richard Goode and Mitsuko Uchida in the 1990s. Serkin formed Marlboro into one of the world’s most prestigious music festivals where musicians gather to make chamber music together; there are no stars, but a community spirit where the experienced guest musicians coach the students.

Apart from his commitments at Curtis and Marlboro, Serkin continued to give many concerts throughout the world, touring Europe and North America every year. At his final Carnegie Hall recital in 1987 when he was eighty-four years old, Serkin played the last three sonatas by Beethoven.

Serkin practised incessantly at the piano, and at times gave the impression that in performance he and the piano were fighting a battle which he would ultimately win. A kind of gritty determination pervades his performances on record. Serkin’s son Peter Serkin said, ‘My dad hated to record. Absolutely hated it.’ All of Serkin’s earliest recordings were made with Busch for HMV and included works by Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Bach, Schumann, and Reger. The one solo work which Serkin recorded in 1936 was Beethoven’s ‘Appassionata’ Sonata Op. 57, a strong, dramatic, convincing performance showing Serkin’s affinity with the composer. One of the best of his chamber music recordings with Adolf and Hermann Busch is of Schubert’s Piano Trio No. 2 in E flat D. 929. Not only is it the finest recording of this work, it is one of the finest of chamber music recordings. During the 1930s and 1940s Serkin also recorded many of Brahms’s chamber works with the Busch Quartet. In 1938 Serkin made his first recording of a Mozart piano concerto, K. 449 in E flat, with the Busch Chamber Players, but it was not until the early 1950s that Serkin began to record for CBS; with George Szell and Alexander Schneider he recorded six of Mozart’s piano concertos. The 1950s also saw recordings of concertos by Schumann, Beethoven, Brahms, Reger, Prokofiev (No. 4, for left hand), and the Burleske by Richard Strauss. In 1960 Serkin made one of his most joyous of recordings: both piano concertos by Mendelssohn were recorded with Eugene Ormandy and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. He had played the G minor Concerto at his Vienna debut, and he championed these works throughout his life.

Although identified in the public eye with Beethoven (his 1962 recording of the ‘Pathétique’, ‘Moonlight’ and ‘Appassionata’ Sonatas was a best-seller), Serkin had never performed the complete cycle of sonatas in public, nor recorded all thirty-two. In 1970, he programmed the complete series at eight recitals in Carnegie Hall. However, around eighteen of them were not in his repertoire, and the task of preparing them along with many other responsibilities including his recent appointment as director of the Curtis Institute proved too much, resulting in the cancellation of the remainder of the series. He did, however, record some of them for CBS at this time, but never recorded all of the sonatas.

During the 1980s Serkin recorded a selection of Mozart piano concertos with the London Symphony Orchestra and Claudio Abbado. In the same decade he recorded all the Beethoven concertos with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Seiji Ozawa, as well as the last three piano sonatas. These were recorded live in Vienna in October 1987 when Serkin was eighty-four years old. These later recordings may have the weight of experience behind them, but even Serkin’s well-drilled fingers had slowed down by this time. Earlier recordings of these works exist, and it should be noted that Serkin recorded many concertos up to three times.

As well as attaining a successful life as a pianist and chamber musician, Serkin left a valuable legacy in the Marlboro Festival in Vermont and in his achievement, with Busch, of putting violinist and pianist on an equal standing in performance.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10)

Founded in Munich in 1949 under Eugen Jochum, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra quickly won an international reputation, collaborating with leading conductors and contemporary composers, the latter notably under the Musica Viva programme. Jochum was succeeded by Rafael Kubelík, who held the position of principal conductor until 1979, to be followed by Colin Davis until 1992, and Lorin Maazel. In 2003 Mariss Jansons became principal conductor. Under successive conductors the repertoire of the orchestra has been widened, as well as under many other distinguished guest conductors. In addition to its broadcasts the orchestra gives regular concerts in Munich and elsewhere, and has participated in numerous festivals and recordings.

Rafael Kubelík was the sixth of the eight sons of the distinguished Czech violinist Jan Kubelík and the Hungarian-born Countess Marianne Csaky-Szell. Between 1921 and 1929 he studied the orchestral repertoire daily by playing four-hand piano arrangements with his uncle František Kubelík, prompting this comment from his father in 1926: ‘He could realise great things. He is eleven, plays splendidly violin, piano, sight-reading scores and has a good knowledge of the orchestra. Some time ago he had a look to one of my orchestral works and asked me to add a horn to a particular part: he was right!’ He entered the Prague Conservatory in 1929 where for the next four years he studied piano, violin and composition.

At the beginning of 1934, Kubelík made his first appearance as a conductor with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, in a programme that included his own Fantasy Op. 2, played by his father, and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4. He accompanied his father at the piano on recital tours through Romania, Italy and America during 1935 and 1936, appeared with the Czech Philharmonic playing a Mozart violin concerto himself, and was appointed as a conductor with the orchestra in 1936. Václav Talich, the orchestra’s chief conductor, sent him on tour with the orchestra to the United Kingdom in 1937 and 1938, and he also appeared as a guest conductor in America during 1937, turning down the offer of a permanent position there. Kubelík was the chief conductor of the Brno Opera between 1939 and 1941, staging the first Czech performances of Berlioz’s Les Troyens there, but after the National Socialist administration closed the theatre, he returned to Prague, where he held the position of chief conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra from 1941 to 1948 in succession to Talich.

Resisting political interference in the orchestra’s affairs, Kubelík conducted a wide repertory with it that included much Czech music. At the end of World War II he led the orchestra in a performance of Smetana’s My Country in Prague’s Old Town Hall Square, supported the nationalisation of the orchestra in 1945 and assisted with the establishment of the Prague Spring Festival; but following the establishment of the Communist regime in what was to become Czechoslovakia he decided to defect while conducting Mozart’s Don Giovanni with the Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the Edinburgh Festival in 1948. Kubelík commented about working under extreme political conditions: ‘I am an anti-communist and anti-fascist. I do not think that artistic freedom can cope with a totalitarian regime. Individuals cannot do anything in a totalitarian country; people who think they can – from their own merits – are really naïve.’ He accepted engagements with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, and also appeared in South America and England, where he was much admired by the members of the BBC Symphony and Philharmonia Orchestras.

Kubelík first appeared at the head of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1949 and made such a positive impression that he was invited to be the orchestra’s chief conductor with effect from 1950, but after three seasons with the orchestra he resigned in 1953 as a result of virulent press attacks from the critic Claudia Cassidy, who disliked the number of contemporary works which he programmed and the employment of black musicians. Having enjoyed great success conducting Janáček’s Kát’a Kabanová with the Sadler’s Wells opera company in London in 1954, Kubelík was appointed chief conductor of the Covent Garden opera company at the Royal Opera House in 1955. Here he conducted the first complete performance in the United Kingdom of Les Troyens as well as legendary stagings of Verdi’s Otello and Janáček’s Jenůfa; and also vigorously promoted the idea of a resident company of permanent singers, which lasted more or less intact until the end of Sir Georg Solti’s regime. Once again however he reacted strongly to personal attacks, which this time came from a former director of opera at Covent Garden, Sir Thomas Beecham, who criticised the employment of foreign conductors: ironically Kubelík was to make some very successful recordings with Beecham’s own post-war orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic.

After resigning from Covent Garden in 1958 Kubelík concentrated on recording and working with many of the finest orchestras in the world, such as those of Berlin and Vienna. Following the death of his first wife as a consequence of a car accident, he married the Australian soprano Elsie Morison, who may be heard in his recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Kubelík had first conducted this orchestra in 1960, in a concert of music by Martinů, Mozart and Beethoven, and became its chief conductor the following year, remaining with it until 1979. These were to be highly productive years: the orchestra’s status as a radio orchestra allowed it to give Kubelík the extensive rehearsal time which had been the subject of criticism in Chicago and London; and freed from commercial constraints, its repertoire could be more adventurous than that of most rival orchestras. His programming was extremely original: for instance in individual seasons he would present religious pieces from Palestrina to Stravinsky (1967–1968); a symphony by Haydn in each concert (1970–1971); dedicate each concert to a single composer (1971–1972); or a complete season to twentieth-century music (1972–1973); or to symphonic poems (1973–1974). He conducted a wide range of operas with the orchestra, including Iphigénie en Tauride by Gluck, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Lohengrin and Parsifal by Wagner, Oberon by Weber, Dalibor by Smetana, Palestrina by Pfitzner, Mathis der Maler by Hindemith, Prometheus and Oedipus der Tyrann by Orff, and Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor by Nicolai. He made numerous recordings with the orchestra and toured with it often.

Kubelík took Swiss citizenship in 1967, becoming involved with the Lucerne Festival; and for a short period was chief conductor of the Metropolitan Opera in New York (1973–1974), an appointment made by a new general director, Goeran Gentele, who died before he was able to take up his post. During the 1970s and early 1980s Kubelík suffered increasingly from poor health, especially arthritis, and by 1985 had effectively ceased to conduct; but he returned to the podium in 1990 to celebrate the transition of his home country to democracy, and once again led the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in a performance of My Country at the Prague Spring Festival. A distinguished composer himself, he gave numerous first performances, including Martinů’s Three Frescoes of Piero della Francesca, Frank Martin’s Sechs Monologe aus ‘Jedermann’, Schoenberg’s Die Jakobsleiter, and Hartmann’s Symphony No. 8. He was critical of his own genius as a conductor, noting, ‘There has not been a single concert in my life of which I could say that every thing matched my hopes, and I gave thousands!’

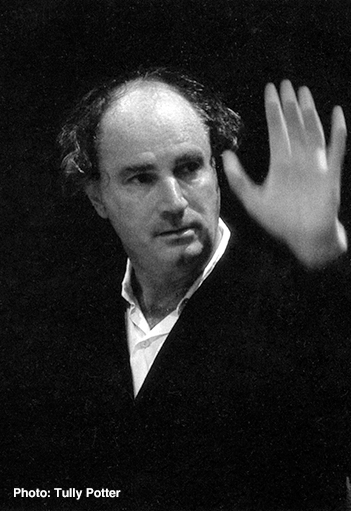

On the podium Kubelík conducted with great energy, ‘throwing the beat off himself’ to quote the graphic description of Sir Charles Mackerras. He was not a disciplinarian, and his style was aptly described as that of ‘the velvet hand in the velvet glove’. His flexibility was ideally suited to the music of late-Romantic composers such as Mahler, and expressiveness was occasionally achieved at the price of rhythmic drive. Kubelík was liked by orchestras across the world, which would all play for him in a heart-warming style that represented the absolute best of the Czech school of musicianship. His discography is large, extending across the whole of the era of the long-playing record, from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. After making a number of 78rpm recordings for EMI, he recorded an extensive repertoire with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for the American company Mercury from 1951 onwards. With the ending of his formal relationship with the Chicago orchestra and therefore with Mercury, he recorded for Decca, including a notable series of recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; and towards the end of the 1950s he returned to EMI, before moving to Deutsche Grammophon, the company which had the closest relationship at this time with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra through its founder and first chief conductor, Eugen Jochum.

Since Kubelík’s death a wide range of radio recordings has been released, which has further extended his already substantial recorded repertoire. Among the numerous highlights of his discography are the complete symphonies of Beethoven (each with a different orchestra), Brahms, Mahler and Schumann; Pfitzner’s Palestrina, Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder, Verdi’s Rigoletto, Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Lohengrin and Parsifal; together with individual works by Bartók, Dvořák, Janáček, Martinů, Mozart, and Smetana. Although he recorded relatively few concertos, those that stand out are Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with the British pianist Solomon; four of the Mozart piano concertos with Clifford Curzon, and Schoenberg’s Piano and Violin Concertos with Alfred Brendel and Zvi Zeitlin respectively.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).

Born in Bonn in 1770, the eldest son of a singer in the Kapelle of the Archbishop-Elector of Cologne and grandson of the Archbishop’s Kapellmeister, Beethoven moved in 1792 to Vienna. There he had some lessons from Haydn and others, quickly establishing himself as a remarkable keyboard player and original composer. By 1815 increasing deafness had made public performance impossible and accentuated existing eccentricities of character, patiently tolerated by a series of rich patrons and his royal pupil the Archduke Rudolph. Beethoven did much to enlarge the possibilities of music and widen the horizons of later generations of composers. To his contemporaries he was sometimes a controversial figure, making heavy demands on listeners by both the length and the complexity of his writing, as he explored new fields of music.

Stage Works

Although he contemplated others, Beethoven wrote only one opera. This was eventually called Fidelio after the name assumed by the heroine Leonora, who disguises herself as a boy and takes employment at the prison in which her husband has been unjustly incarcerated. This escape opera, for which there was precedent in contemporary France, ends with the defeat of the evil prison governor and the rescue of Florestan, testimony to the love and constancy of his wife Leonora. The work was first staged in 1805 and mounted again in a revised performance in 1814, under more favourable circumstances. The ballet The Creatures of Prometheus was staged in Vienna in 1801, and Beethoven wrote incidental music for various other dramatic productions, including Goethe’s Egmont, von Kotzebue’s curious The Ruins of Athens, and the same writer’s King Stephen.

Choral and Vocal Music

Beethoven’s most impressive choral work is the Missa solemnis, written for the enthronement of his pupil Archduke Rudolph as Archbishop of Olmütz (Olomouc) although finished too late for that occasion. An earlier work, the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, is less well known. In common with other composers, Beethoven wrote a number of songs. Of these the best known are probably the settings of Goethe, which did little to impress the venerable poet and writer (he ignored their existence), and the cycle of six songs known as An die ferne Geliebte (‘To the Distant Beloved’). The song ‘Adelaide’is challenging but not infrequently heard.

Orchestral Music

Symphonies

Beethoven completed nine symphonies, works that influenced the whole future of music by the expansion of the traditional Classical form. The best known are Symphony No. 3, ‘Eroica’, originally intended to celebrate the initially republican achievements of Napoleon; No. 5; No. 6, ‘Pastoral’; and No. 9, ‘Choral’. The less satisfactory ‘Battle Symphony’ celebrates the earlier military victories of the Duke of Wellington.

Overtures

For the theatre and various other occasions Beethoven wrote a number of overtures, including four for his only opera, Fidelio (one under that name and the others under the name of the heroine, Leonora). Other overtures include Egmont, Coriolan, Prometheus, The Consecration of the House and The Ruins of Athens.

Concertos

Beethoven completed one violin concerto and five piano concertos, as well as a triple concerto for violin, cello and piano, and the curious Choral Fantasy for solo piano, chorus and orchestra. The piano concertos were for the composer’s own use in concert performance. No. 5, the so-called ‘Emperor’ Concerto, is possibly the most impressive. The single Violin Concerto, also arranged for piano, is part of the standard violin repertoire along with two romances (possible slow movements for an unwritten violin concerto).

Chamber Music

Beethoven wrote 10 sonatas for violin and piano, of which the ‘Spring’ and the ‘Kreutzer’ are particular favourites with audiences. He extended very considerably the possibilities of the string quartet. This is shown even in his first set of quartets, Op. 18, but it is possibly the group of three dedicated to Prince Razumovsky (the ‘Razumovsky’ Quartets, Op. 59) that are best known. The later string quartets offer great challenges to both players and audience, and include the remarkable Grosse Fuge—a gigantic work, discarded as the final movement of the String Quartet, Op. 130, and published separately. Other chamber music includes a number of trios for violin, cello and piano, with the ‘Archduke’ Trio pre-eminent and the ‘Ghost’ Trio a close runner-up, for very different reasons. The cello sonatas and sets of variations for cello and piano (including one set based on Handel’s ‘See, the conqu’ring hero comes’ from Judas Maccabaeus and others on operatic themes from Mozart) are a valuable part of any cellist’s repertoire. Chamber music with wind instruments and piano include the Quintet, Op. 16, for piano, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon. Among other music for wind instruments is the very popular Septet, scored for clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello and double bass, as well as a trio for two oboes and cor anglais, and a set of variations on a theme from Mozart’s Don Giovanni for the same instruments.

Piano Music

Beethoven’s 32 numbered piano sonatas make full use of the developing form of the piano, with its wider range and possibilities of dynamic contrast. Other sonatas not included in the 32 published by Beethoven are earlier works, dating from his years in Bonn. There are also interesting sets of variations, including a set based on ‘God Save the King’and another on ‘Rule, Britannia’, variations on a theme from the ‘Eroica’ Symphony, and a major work based on a relatively trivial theme by the publisher Diabelli. The best known of the sonatas are those that have earned themselves affectionate nicknames: the ‘Pathétique’, ‘Moonlight’, ‘Waldstein’, ‘Appassionata’, ‘Les Adieux’ and ‘Hammerklavier’. Less substantial piano pieces include three sets of bagatelles, the all too well-known Für Elise, and the Rondo a capriccio, known in English as ‘Rage Over a Lost Penny’.

Dance Music

Famous composers like Haydn and Mozart were also employed in the practical business of providing dance music for court and social occasions. Beethoven wrote a number of sets of minuets, German dances and contredanses, ending with the so-called Mödlinger Dances, written for performers at a neighbouring inn during a summer holiday outside Vienna.