Available Worldwide

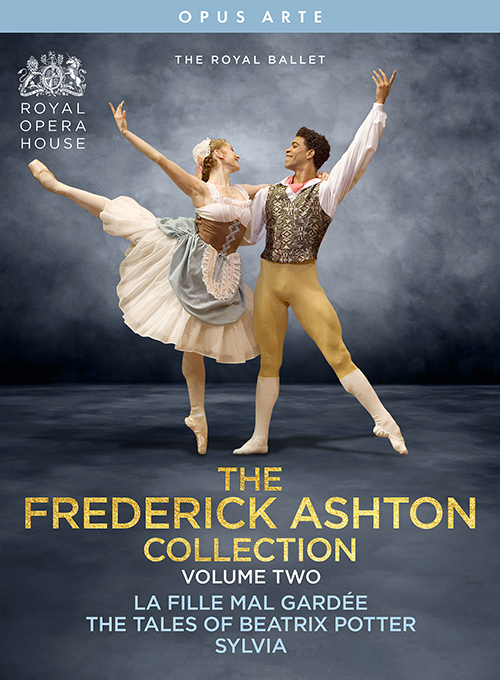

FREDERICK ASHTON COLLECTION (THE), Vol. 2 (Royal Ballet, 2005-2007) (3-DVD Box Set) (NTSC)

Tracklist

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Szilvay, Peter (Conductor)

Georg Solti studied as a pianist at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest, where his teachers included Bartók, Kodály, and Leo Weiner. Here he developed his fidelity to the tempo, rhythm and dynamic of the written text, using these as the starting points of interpretation throughout his life. Having decided at an early age to be a conductor, Solti became a répétiteur at the Budapest Opera, working there in this position from 1931 to 1939. During 1937 he was engaged to play for the rehearsals of Die Zauberflöte conducted by Toscanini at the Salzburg Festival; the Italian maestro’s impact upon Solti was great, reinforcing his deep respect for the written text, as well as his ethic of continuous work and study. He made his operatic debut as a conductor at the Budapest Opera leading Le nozze di Figaro on 11 March 1938, the day of the Anschluss or German annexation of Austria.

Soon a fascist regime was in place in Hungary and Solti, a Jew, was sacked by the Budapest Opera. In order to seek a recommendation to work in America Solti travelled to Switzerland in 1939 to visit Toscanini. However the attempt to reach America came to nothing, and so in conducting terms, Solti’s career was stalled for the six years of World War II while he was effectively trapped in Switzerland. Here, unable to conduct but wishing to do so, he developed great prowess as a pianist, winning the first prize in the piano section of the Geneva International Music Competition in 1942.

As a result of this enforced delay to the continuation of his chosen career, by the end of the war Solti was sufficiently desperate to conduct as to be prepared to travel to Munich on the off-chance that a fellow ex-pupil from the Franz Liszt Academy, Edward Kilenyi, now a major in the American army, might be able to find him a conducting position. Because of the de-Nazification procedures, there were no German conductors of note able to work in this part of the country; so Solti, following a successful debut in Stuttgart, was immediately offered the job of music director of the Bavarian State Opera: thus in one bound finding himself in a position which normally would be awarded only to a conductor with an extensive pedigree. At this time Solti also made a key contact, through the Swiss tenor Max Lichtegg, with Maurice Rosengarten, who was responsible for classical music at Decca Records. By convincing Rosengarten that he was a conductor to watch—and aided by the Munich appointment—Solti commenced a relationship with Decca in 1947 which continued virtually without interruption for fifty years.

An unusual characteristic of Solti’s conducting career, which was based very much on relationships, was his longevity in formal ‘command’ positions. Between 1946 and 1991, when he ended his tenure as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, he held only four appointments, all as music director of the following musical institutions: Bavarian State Opera, Munich (1946–1952), Frankfurt Opera (1952–1961), Covent Garden (later Royal) Opera Company, London (1961–1971); Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1969–1991). These posts covered a period of forty-five years, and they formed the bedrock upon which a highly active programme of recordings and international guest engagements was built.

Another key factor in the development of Solti’s recording career was his relationship with the record producer John Culshaw. Culshaw first heard Solti conduct in 1949, at a performance of Der Rosenkavalier in Munich, and that autumn he produced Solti’s first record with the London Philharmonic Orchestra for Decca, a disc of Haydn’s Symphony No 103. The following year Culshaw heard Solti again in Munich, this time conducting Die Walküre, and was sufficiently highly impressed to make Solti his first choice, after Knappertsbusch, to conduct the Ring on record. The Decca connection enabled Solti and Culshaw to keep their relationship in play, while the 1957 recordings of Arabella (with Solti substituting for Böhm) and of Act III of Die Walküre demonstrated Solti to be a conductor of consequence in both Strauss and Wagner. Decca’s 1958 decision to record Das Rheingold, the springboard to the later recording of the entire Ring cycle, gave Solti the platform from which to leap into the international musical firmament, a rise which the success of these recordings certainly facilitated. By 1959, the year of his Covent Garden debut and of the offer of the music directorship there, he had become established as a recording and opera conductor of the first rank.

Solti built the Covent Garden Opera, later renamed during his music directorship as the Royal Opera Company, into a company of the highest international quality. He introduced for the first time an uncompromising drive towards the best possible standards, replacing the repertoire with the stagione system, whilst also developing an ensemble of mainly British singers, most of whom went on to enjoy international careers. He expanded the repertoire by introducing works such as Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, and engaged outstanding theatrical directors such as Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn to deliver productions of high quality. Throughout the 1960s Decca sustained and developed this reputation by recording Solti in three key repertoire strands: Wagner, Richard Strauss and Mahler. By the time he came to take over the music directorship of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1969 Solti was firmly established internationally as a conductor to be mentioned in the same breath as Herbert von Karajan. By bringing together Decca and the Chicago orchestra he created a relationship which ensured a stream of recordings that ran up to and beyond his resignation as music director in 1991.

Solti’s years with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra may now be seen as a direct continuation of the musical standards and expectations created by his formidable predecessor, Fritz Reiner. The virtuosity achieved by Solti and this orchestra has rarely been equalled and never exceeded. During his time in Chicago Solti also accepted appointments as chief conductor of the Orchestre de Paris (1972–1975) and as principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (1979–1981) and conducted a new production of the Ring at the Bayreuth Festival in 1983. Knighted in 1971, Sir Georg maintained a programme of guest-conducting engagements throughout the world in both the opera house and the concert hall from 1991 to his death in 1997. His last public appearance was conducting at the Gala performance that marked the closure of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in the summer of 1997, prior to its renovation.

Solti was a most energetic conductor in both rehearsal and performance, with a frequently sharp and stabbing conducting style. At the same time he was also capable of producing the most beautiful legato playing. He insisted upon great rhythmic precision and tight ensemble, allied to the acute observation of dynamics and of course the highest technical standards of execution. The result in the works of the ‘two Richards’, Wagner and Strauss, was to present their music with a discipline which had rarely been encountered previously. His emphasis upon line and phrasing also paid great dividends in the music of Mozart and Verdi, whose works he conducted with complete mastery. His most enduring legacy is the vast catalogue of operatic and symphonic recordings which he made for Decca, in which pride of place must certainly go to his account of Der Ring des Nibelungen with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Other outstanding operatic recordings include, by Richard Strauss, Arabella, Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Der Rosenkavalier, Elektra and Salome; by Richard Wagner, Tannhäuser and Parsifal; by Verdi, Don Carlos, Rigoletto and Un ballo in maschera; and by Mozart the three da Ponte operas as well as Die Zauberflöte. Solti’s drive and precision are extremely well displayed in his account of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Eurydice. Of his orchestral recordings, particularly memorable are his accounts of works by his teachers Bartók and Kodály, together with the symphonies of Mahler and most notably those of Elgar. No Solti recording is without some point of interest: his stature as one of the most outstanding conductors of the twentieth century is fully confirmed through this legacy.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).

Wagner was a remarkable innovator in both the harmony and structure of his work, stressing his own concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the ‘total work of art’, in which all the arts were brought together into a single unity. He was prepared to sacrifice his family and friends in the cause of his own music, and his overt anti-Semitism has attracted unwelcome attention to ideas that are remote from his real work as a musician. In the later part of his career Wagner enjoyed the support of King Ludwig II of Bavaria and was finally able to establish his own theatre and festival at the Bavarian town of Bayreuth. He developed the use of the leitmotif (in German Leitmotiv – ‘leading motif’) as a principle of musical unity, his dramatic musical structure depending on the interweaving of melodies or fragments of melody associated with characters, incidents or ideas in the drama. His prelude to the love tragedy Tristan und Isolde led to a new world of harmony.

Operas and Music Dramas

Wagner won his first operatic success in Dresden with the opera Rienzi, based on a novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. This was followed a year later, in 1843, by Der fliegende Holländer (‘The Flying Dutchman’), derived from a legend recounted by Heine of the Dutchman fated to sail the seas until redeemed by true love. Tannhäuser, dealing with the medieval Minnesinger of that name, was staged in Dresden in 1845. Wagner’s involvement in the revolution of 1848 and subsequent escape from Dresden led to the staging of his next dramatic work, Lohengrin, in Weimar, under the supervision of Liszt. The tetralogy The Ring—its four operas Das Rheingold, Die Walküre (‘The Valkyrie’), Siegfried and Götterdämmerung (‘The Twilight of the Gods’)—is a monument of dramatic and musical achievement that occupied the composer for a number of years. Other music dramas by Wagner include Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (‘The Mastersingers of Nuremberg’), and his final work, Parsifal.

Orchestral Music

The best known of Wagner’s orchestral compositions is the Siegfried Idyll, an aubade written for the composer’s second wife, Cosima (illegitimate daughter of Liszt and former wife of Wagner’s friend and supporter Hans von Bülow). His early works also include a symphony.

Songs

At the root of Wagner’s drama of forbidden love, Tristan und Isolde, was his own affair with Mathilde Wesendonck, wife of a banker upon whose support he relied during years of exile in Switzerland. The five Wesendonck-Lieder are settings of verses by Mathilde Wesendonck.