Exclusively available for streaming and download.

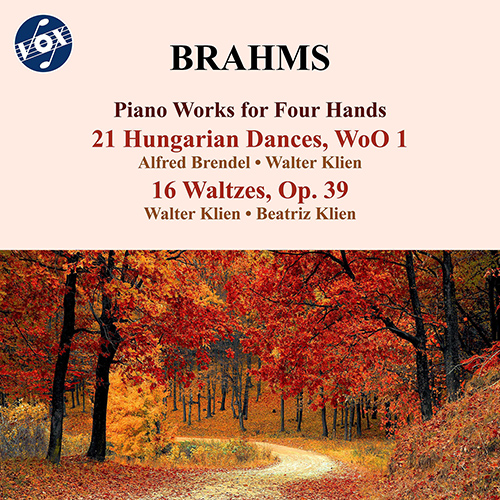

BRAHMS, J.: 21 Hungarian Dances, WoO 1 / 16 Waltzes, Op. 39 (version for piano 4 hands) (Brendel, W. Klien, B. Klien)

Tracklist

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Brendel, Alfred (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Walter (piano)

Klien, Beatriz (piano)

Klien, Beatriz (piano)

Alfred Brendel’s parents were not musical and he was not a child prodigy. Due to his father’s work, Brendel and his family moved around Yugoslavia and Austria, and whilst in Zagreb young Alfred began piano lessons with Sofia Dezelic. When the family then moved to Graz, Brendel enrolled at the Graz Conservatory and made his début in the city at the age of seventeen. He never studied with a famous teacher, and from the time he left the Graz Conservatory his only influence was the pianist Edwin Fischer.

His formative years were spent studying the lives of the great composers and listening to recordings, particularly those of Edwin Fischer, Alfred Cortot and Artur Schnabel. In 1949 he attended a master-class by Edwin Fischer in Lucerne and has always credited Fischer as the most important pianistic influence in his life. In the same year, he entered the Busoni Competition in Bolzano and was awarded third prize. During the 1950s Brendel had some success as a touring pianist in Europe but did not make his London début until 1958. However, during the 1950s he was working very hard at building repertoire, and by the early 1960s he was playing all the Beethoven piano sonatas in public. By playing the complete set across eight concerts in London’s Wigmore Hall in 1962, Brendel carved himself a niche; and his recordings for Vox made between 1958 and 1964, of all of Beethoven’s solo piano works, raised his profile immeasurably on the international scene. From then until the present day Brendel has been in demand throughout the world as a soloist, often performing the complete sonatas and concertos of Beethoven. He has lived in London since he moved there in 1972. In the early 1980s Brendel played the complete Beethoven sonatas in ten major European cities, and he has also given series of recitals devoted exclusively to Schubert throughout Europe, Japan, America and Canada. The centenary of Liszt’s death saw Brendel giving many recitals devoted to the music of this composer. He has received honorary degrees from the universities of Sussex, London and Oxford.

Although largely based around Beethoven and Schubert, Brendel’s repertoire also includes Bach, Liszt and Busoni. In fact, after Beethoven and Schubert, Liszt is the composer most associated with Brendel. Only early in his career did he play Chopin and virtuoso Russian works, such as Stravinsky’s Three Movements from Petrushka, Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, and Balakirev’s Islamey; and today he rarely performs French music and only a few contemporary works by Schoenberg and Berg. He knows what he does best and what his audiences want to hear from him, and in Beethoven and Schubert particularly Brendel is able to realise his belief that the music and message of the composer are the most important things: not the piano or the performer.

Brendel follows in the line of Schnabel and Fischer as a cerebral pianist rather than one whose playing is based solely on his emotions; but he takes this idea further, causing some critics to complain of a lack of tone, colour and emotional depth. He is, without doubt, an intelligent musician whose wit and humour is apparent in his writings Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts (1976) and Music Sounded Out (1990).

Brendel’s discography is huge. His first series of recordings was made for the American company Vox and recorded in Vienna. In the late 1950s he recorded both concertos by Liszt as well as his Totentanz, Malédiction and arrangement of Schubert’s ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy, all for piano and orchestra. In addition to Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor and operatic paraphrases and transcriptions, Brendel recorded some of the late piano pieces, which were even more rarely heard then than they are now.

Brendel excels in the larger works of Beethoven, such as the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata Op. 106 and ‘Diabelli’ Variations Op. 120.

Having recorded for Philips for more than thirty years, his catalogue with that company is large, and the recording of The Art of Alfred Brendel on twenty-five compact discs gives an excellent overview of his work. Included in the survey are five sets of works by Mozart and Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert and Liszt. The final set of five discs contains music by Brahms (both piano concertos) and Schumann (the Piano Concerto Op. 54 and many of the major works, including the Fantasie in C major Op. 17). Sometimes Brendel does not seem to reveal the conflicts and inner struggles inherent in Schumann’s music, where an academic approach can override the fantastical elements, but one is always aware that Brendel’s combination of intelligence and humour underlines everything he plays.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).

Son of a well-known artist, Erika Giovanna Klien, Walter Klien began playing the piano at the age of five. He first studied piano, composition and conducting in Frankfurt, then Graz. In 1946 he began studies with Josef Dichler at the Vienna Academy of Music and completed his piano studies with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. Klien also took lessons in composition from Paul Hindemith. During the early 1950s Klien participated in competitions, winning prizes at both the 1951 and 1952 Busoni Competitions in Bolzano.

By the time of his debuts in Britain and America, Klien was already known through his recordings. His London debut in February 1968, made in the Purcell Room, the smallest of the three concert halls on the South Bank, was a great success. ‘The Purcell Room can rarely have heard a finer recital than that given on Friday by the Austrian pianist Walter Klien.’ The critic of The Times went as far as to say, ‘Everything he played was marked by extreme refinement, profound intelligence, and near-perfect clarity—sustained by an impressive technique.’

During the 1960s and 1970s Klien toured the world playing in North and South America, Europe, the Far East, the Soviet Union and at most of the major musical festivals. In 1972 Rudolf Serkin made him a faculty member of the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont. Klien worked with violinists Wolfgang Schneiderhan and Edith Peinemann and singers Julius Patzak, Hans Hotter and Hermann Prey. Klien’s style was one of coolness and precision with a clarity of technique. As Donald Manildi described him, ‘Tonally and technically he left little to be desired, and the quiet authority of his approach did not preclude ample vitality and wit where needed.’ His repertoire was based around the Austro-German Classical works for which he became famous, but he also played twentieth-century music. From the mid-1960s he recorded for the American label Vox, and most of these recordings appeared on the Turnabout label in Britain. He was the first pianist to record the complete solo piano music of Brahms, and he also recorded the complete piano sonatas of Mozart for which he received the Wiener Flötenuhr Prize in 1969. Ten years later, in June 1979, Klien finished his recording of the complete piano sonatas of Schubert. He did not, however, attempt to complete the unfinished sonatas: ‘You do not write third and fourth movements for the C major. I studied composition and I wrote symphonies and operas but I would not like to finish a Schubert sonata.’ With fellow Vox artist Alfred Brendel, Klien recorded duets by Dvořák, Brahms and Mozart, but he never seemed to attain the public adulation that Brendel received. Also for Vox, Klien recorded major works by Schumann, some Haydn piano sonatas, and a selection of Grieg including the Ballade Op. 24. There are not many concerto recordings, but one Vox disc includes Stravinsky’s Concerto for Piano and Wind and Concertinos by Janáček and Honegger.

With Schneiderhan Klein recorded such works as Richard Strauss’s Violin Sonata and music by Schubert and Dvořák. In the early 1980s he recorded Mozart’s sonatas for violin and piano with Arthur Grumiaux for Philips.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).

Born in Hamburg, the son of a double bass player and his older seamstress wife, Brahms attracted the attention of Schumann, to whom he was introduced by the violinist Joachim. After Schumann’s death he maintained a long friendship with the latter’s widow, the pianist Clara Schumann, whose advice he always valued. Brahms eventually settled in Vienna, where to some he seemed the awaited successor to Beethoven. His blend of Classicism in form with a Romantic harmonic idiom made him the champion of those opposed to the musical innovations of Wagner and Liszt. In Vienna he came to occupy a position similar to that once held by Beethoven, his gruff idiosyncrasies tolerated by those who valued his genius.

Orchestral Music

Brahms wrote four symphonies, massive in structure, and all the result of long periods of work and revision. The two early serenades have their own particular charm, while Variations on a Theme by Haydn—in fact the St Anthony Chorale, used by that composer—enjoys enormous popularity, as it illustrates a form of which Brahms had complete mastery. A pair of overtures—the Academic Festival Overture and the Tragic Overture—and arrangements of his Hungarian Dances complete the body of orchestral music without a solo instrument. His concertos consist of two magnificent and demanding piano concertos, a violin concerto and a splendid double concerto for violin and cello.

Chamber Music

Brahms completed some two dozen pieces of chamber music, and almost all of these have some claim on our attention. For violin and piano there are three sonatas, Opp 78, 100 and 108, with a separate Scherzo movement for a collaborative sonata he wrote with Schumann and Dietrich for their friend Joachim. For cello and piano he wrote two fine sonatas: Opp 38 and 99. There are two late sonatas, written in 1894, for clarinet/viola and piano, Op 120, each version deserving attention, as well as the Clarinet Trio, Op 114, for clarinet, cello and piano, and the Clarinet Quintet, Op 115, for clarinet and string quartet, both written three years earlier. In addition to this, mention must be made of the three piano trios, Opp 8, 87 and 101; the Horn Trio, Op 40 for violin, horn and piano; three piano quartets, Opp 25, 26 and 60; the Piano Quintet, Op 34; and three string quartets, Opp 51 and 67. Two string sextets, Opp 18 and 36, and two string quintets, Opp 88 and 111, complete the list.

Piano Music

If all the chamber music of Brahms should be heard, the same may be said of his music for piano. Brahms showed a particular talent for the composition of variations, and this is aptly demonstrated in the famous Variations on a Theme by Handel, Op 24, with which he made his name at first in Vienna, and the ‘Paganini’ Variations, Op 35, based on the theme of the great violinist’s Caprice No. 24. Other sets of variations show similar skill, if not the depth and variety of these major examples of the art. Four Ballades, Op 10, include one based on a real Scottish ballad, Edward, a story of parricide. The three piano sonatas, Opp 1, 2 and 5, relatively early works, are less well known than the later piano pieces, Opp 118 and 119, written in 1892, and the Fantasias, Op 116, of the same year. Music for four hands, either as duets or for two pianos, includes the famous Hungarian Dances (often heard in orchestral and instrumental arrangement) and a variety of original compositions and arrangements of music better known in orchestral form.

Vocal and Choral Music

There is again great difficulty of choice when we approach the large number of songs written by Brahms, which were important additions to the repertoire of German Lied (art song). The Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op 52, for vocal quartet and piano duet are particularly delightful, while the solo songs include the moving Four Serious Songs, Op 121, reflecting preoccupations as his life drew to a close. ‘Wiegenlied’ (‘Cradle Song’) is one of a group of five songs, Op 49; the charming ‘Vergebliches Ständchen’ (‘Vain Serenade’) appears in the later set Five Romances and Songs, Op 84, and there are two particularly wonderful songs for contralto, viola and piano, Op 91: ‘Gestillte Sehnsucht’ (‘Tranquil Yearning’) and the Christmas ‘Geistliches Wiegenlied’ (‘Spiritual Cradle-Song’), Op 91, based on the carol ‘Josef, lieber Josef mein’(‘Joseph dearest, Joseph mine’).

Major choral works by Brahms include the monumental A German Requiem, Op 45, a setting of biblical texts; the Alto Rhapsody, Op 53, with a text derived from Goethe; the Schicksalslied (‘Song of Destiny’), Op 54 (a setting of Hölderlin); and a series of accompanied and unaccompanied choral works, written for the choral groups with which he was concerned in Hamburg and in Vienna.