Tracklist

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

Brandt, Matthias (Reader)

Hobmeier, Brigitte (Reader)

Lückenhaus, Benedict (Reader)

Tregor, Michael (Reader)

Albus, Thomas (Reader)

Baumann, Christian (Reader)

Dücker, Folkert (Reader)

Himmelstoß, Beate (Reader)

May, Jerzy (Reader)

Schild, Katja (Reader)

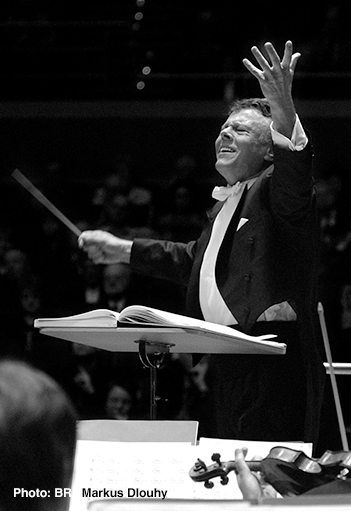

Jansons, Mariss (Conductor)

Jansons, Mariss (Conductor)

Jansons, Mariss (Conductor)

Jansons, Mariss (Conductor)

Jansons, Mariss (Conductor)

Founded in Munich in 1949 under Eugen Jochum, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra quickly won an international reputation, collaborating with leading conductors and contemporary composers, the latter notably under the Musica Viva programme. Jochum was succeeded by Rafael Kubelík, who held the position of principal conductor until 1979, to be followed by Colin Davis until 1992, and Lorin Maazel. In 2003 Mariss Jansons became principal conductor. Under successive conductors the repertoire of the orchestra has been widened, as well as under many other distinguished guest conductors. In addition to its broadcasts the orchestra gives regular concerts in Munich and elsewhere, and has participated in numerous festivals and recordings.

Mariss Jansons’s earliest memories were of his father, the conductor Arvid Jansons, conducting opera and ballet: ‘As a very small boy, three years old, I was always observing… I went to my father’s rehearsals. When I came home, I put my book on the table and started to conduct. I changed my trousers because they were for rehearsal, not for concert. I played at being artistic director, drawing up programmes for subscription seasons.’ He learned to play the violin in Riga, and in 1957 entered the Leningrad Conservatory, where he studied conducting with Rabinovich, as well as the piano and violin. He made his public conducting debut prior to graduating with honours and then studied with Hans Swarowsky at the Vienna Academy of Music from 1969 to 1972. Having been assistant to Herbert von Karajan at Salzburg in 1969 and 1970, Jansons took first prize at the International von Karajan Foundation Conducting Competition in 1971 and in the same year was appointed associate conductor of the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, working with the orchestra’s distinguished chief conductor Evgeny Mravinsky. The influence of this period in his career was great, especially in terms of standards and expectations. ‘The atmosphere was so pressured,’ he has recalled. ‘Mravinsky demanded such high standards, everybody was afraid to fall below. There was Richter, Gilels, (David) Oistrakh—such quality.’

In 1979 Jansons was appointed to his first chief conductorship, taking charge of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, whose standards he raised significantly. With this orchestra he made many recordings including a highly praised cycle of the Tchaikovsky symphonies, and toured extensively throughout Europe (including appearances at the Salzburg Festival and at the Promenade Concerts in London) and the Far East, both activities greatly enhanced the reputations of conductor and orchestra. He became the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra’s associate principal conductor in 1985, a position which he retained until 1999. In addition to his work in the USSR and Norway, Jansons was also active during this time in Great Britain, conducting the BBC National Symphony Orchestra of Wales frequently, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, of which he was principal guest conductor from 1992 to 1997. As with most conductors of Jansons’s calibre, the work involved with these permanent positions was combined with guest appearances with most of the major European and American orchestras, such as the Berlin Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Royal Amsterdam Concertgebouw and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestras. He also maintained the distinguished Russian tradition of teaching conducting when in 1995 he became professor of conducting at the St Petersburg Conservatory, as his father had been before him.

Jansons’s career took a decisive step forward in 1997 when he became the chief conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in succession to Lorin Maazel. Here too he dramatically improved the standards of the orchestra, an achievement which was acknowledged on its numerous foreign tours even though the orchestra had to work hard at home to increase audience levels. In 1996 Jansons suffered a heart attack while conducting a performance of La Bohème in Oslo and as a result had to take more care of his health. In 2002 he therefore decided not to renew his contract with the Pittsburgh Orchestra after the end of the 2003–2004 concert season and reduced his work in North America, thus cutting down considerably on travelling. He accepted instead the appointments of chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, once again in succession to Maazel, with effect from the autumn of 2003, and of chief conductor of the Royal Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra from the autumn of 2004.

In style, Jansons’s conducting was a powerful combination of discipline and inspiration. At his best, he had the ability to invest scores with a range of colour and timbre achieved by very few other conductors. He was extremely demanding of orchestral players without being autocratic or overbearing and tried many different approaches to interpretation. Intensive rehearsal produces readings in which the level of musical nuance and subtlety is unusually high: at the same time Jansons was not wholly predictable in performance and often used the inspiration of the moment to make fresh demands upon his players. The associate concert-master of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra has commented on this: ‘Mariss expects intuitive playing and aspires to changing the playing nightly. He expects a kind of musical intuition and a personal involvement.’ The purpose of this approach is to go beyond the notes to a deeper experience: to quote Jansons himself, ‘Imagination is what players expect from a conductor. You must give them what is behind the notes—which is atmosphere, imagination and content. To play the notes is not interesting. But what it means, the cosmic level at which they are detached from problems of playing, that is my job as a conductor.’ The results of this approach are performances that are spontaneous, imaginative and at best very moving, while at the same time being technically highly assured. Jansons himself was clear about his overall objective in performance: ‘Most important for me is that during a performance there is a temperature, because then the public will jump from their seats and after the concert will say, “It was a great experience.” If they come and hear nice tunes but are not touched and excited by the performance, this is very dangerous.’

Jansons’s early recordings appeared mainly on the Chandos label, but he signed an exclusive contract with EMI in 1986 and had since recorded an extensive repertoire with several different orchestras for this company. Highlights of his discography include the complete Tchaikovsky symphonies with the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, the complete Rachmaninov symphonies with the St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, and several notable readings of the Shostakovich symphonies with various orchestras. Several of his recordings have received international awards: that of Shostakovich’s Symphony No 7 with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra won an Edison Award in 1989 and his interpretation of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra won the Dutch Luister Award.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).

The son of a bookseller, publisher and writer, Robert Schumann showed early abilities in both music and literature, the second facility used in his later writing on musical subjects. After brief study at university, he was allowed by his widowed mother and guardian to undertake serious study of the piano with Friedrich Wieck, whose favourite daughter Clara was later to become Schumann’s wife. His ambitions as a pianist were thwarted by a weakness in the fingers of one hand, but the 1830s nevertheless brought a number of compositions for the instrument. The year of his marriage, 1840, was a year of song, followed by attempts in which his young wife encouraged him at more ambitious forms of orchestral composition. Settling first in Leipzig and then in Dresden, the Schumanns moved in 1850 to Düsseldorf, where Schumann had his first official appointment, as municipal director of music. In 1854 he had a serious mental breakdown, followed by two years in the asylum at Endenich before his death in 1856. As a composer Schumann’s gifts are clearly heard in his piano music and in his songs.

Orchestral Music

Symphonies

Schumann completed four symphonies, after earlier unsuccessful attempts at the form. The first, written soon after his marriage and completed early in 1841, is known as ‘Spring’ and has a suggested programme. His Second Symphony followed in 1846, and the Third Symphony, ‘Rhenish’, a celebration of the Rhineland and its great cathedral at Cologne, was written in Düsseldorf in 1850. Symphony No. 4 was in fact an earlier work, revised in 1851 and first performed in Düsseldorf in 1853. The Overture, Scherzo and Finale, Op. 52 was described by the composer as a ‘symphonette’.

Concertos

Schumann’s only completed piano concerto was started in 1841 and finished in 1845. The Cello Concerto of 1850 was first performed four years after Schumann’s death, while the 1853 Violin Concerto had to wait over 80 years before its first performance in 1937. The Konzertstück for four French horns is an interesting addition to orchestral repertoire, and his Introduction and Allegro for piano and orchestra was completed in 1853.

Overtures

Schumann’s only completed opera, Genoveva, was unsuccessful in the theatre, but its overture holds a place in concert-hall repertoire, along with an overture to Byron’s Manfred, again first intended for the theatre. Concert overtures include Die Braut von Messina (‘The Bride from Messina’), based on Schiller’s play of that name; Julius Cäsar, based on Shakespeare; and Hermann und Dorothea, based on Goethe. A setting of scenes from Goethe’s Faust also includes an overture.

Chamber Music

Schumann wrote three string quartets in 1842, a fertile period that also saw the composition of a piano quintet and a piano quartet. Other important chamber music by Schumann includes three piano trios, three violin sonatas, and a number of shorter character pieces that include the Märchenbilder for viola and piano, collections of Phantasiestücke with alternative instrumentation, the Fünf Stücke im Volkston for cello (or violin) and piano, and other short pieces generally suggesting a literary or otherwise extra-musical programme.

Choral and Vocal Music

Schumann wrote a number of part-songs for mixed voices, for women’s voices and for men’s voices, including four collections of Romanzen und Balladen and two of Romanzen for women’s voices. His choral works with orchestra include Scenes from Goethe’s Faust; Das Paradies und die Peri, based on Thomas Moore’s poem Lalla Rookh; and Requiem for Mignon, based on Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister. In his final years he wrote a Mass and a Requiem. The solo songs of Schumann offer a rich repertoire and are an important addition to the body of German Lieder. From these many settings mention may be made of the collections and song cycles Myrthen, Op. 25, Liederkreis, Op. 39, Frauenliebe und -leben, Op. 42, and Dichterliebe, Op. 48, all written in the ‘Year of Song’, 1840.

Piano Music

The piano music of Schumann, whether written for himself, for his wife, or, in later years, for his children, offers a wealth of material. From the earlier period comes Carnaval—a series of short musical scenes with motifs derived from the letters of the town of Asch; this was the home of a fellow student of Friedrich Wieck called Ernestine von Fricken, to whom Schumann was briefly engaged. The same period brought the Davidsbündlertänze (‘Dances of the League of David’), a reference to the imaginary league of friends of art against the surrounding Philistines. This decade also brought the first version of the monumental Symphonic Studies (based on a theme by the father of Ernestine von Fricken) and the well-known Kinderszenen (‘Scenes of Childhood’). Kreisleriana has its literary source in the Hoffmann character Kapellmeister Kreisler, Papillons (‘Butterflies’) has a source in the work of the writer Jean Paul, and Noveletten has a clear literary reference in the very title. Later piano music by Schumann includes the Album für die Jugend (‘Album for the Young’) of 1848, Waldszenen (‘Forest Scenes’) of 1849, and the collected Bunte Blätter (‘Coloured Leaves’) and Albumblätter (‘Album Leaves’) drawn from earlier work.