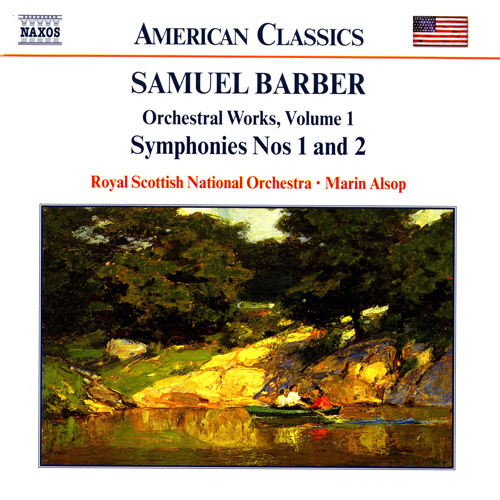

BARBER, S.: Orchestral Works, Vol. 1 - Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 / First Essay for Orchestra (Royal Scottish National Orchestra, M. Alsop)

Tracklist

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alsop, Marin (Conductor)

Alfred Cortot’s mother was Swiss and his father French. After music lessons in the company of his sisters, young Alfred moved with his family to Paris where he joined the Paris Conservatoire at the age of nine. There, he studied piano with Émile Descombes (1829–1912) and, at the age of fifteen, joined the class of Louis Diémer. After winning the premier prix in 1896, Cortot made his debut the following year with Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, and in piano duet recitals with Edouard Risler playing arrangements of Wagner. His enthusiasm for the music of Wagner led to his appointment as choral coach and then assistant conductor at Bayreuth, working under Felix Mottl and Hans Richter. Cortot’s experiences in Bayreuth left him eager to introduce Wagner’s music to French audiences. In 1902 he founded the Société des Festivals Lyriques and in May of the same year conducted the Paris première of Götterdämmerung and a successful Tristan and Isolde. The following year Cortot organised another society through which he gave performances of major works such as Brahms’s Ein Deutsches Requiem, Liszt’s St Elisabeth, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and Wagner’s Parsifal. A year later in 1904 Cortot became conductor of the Société Nationale, promoting works by contemporary French composers.

After all his conducting activities Cortot formed one of the most famous of piano trios with his friends Jacques Thibaud and Pablo Casals and also began to tour Europe as a solo pianist. Although appointed by Fauré to a teaching post at the Paris Conservatoire, Cortot had such an extensive career as a pianist that he was invariably away on tour. In 1918 he made his first tour of America, and over the next eleven years returned five more times. The following year he founded the École Normale de Musique for which he appointed a hand-picked staff, himself giving tuition there until 1961. Cortot’s most famous students include Magda Tagliaferro, Clara Haskil and Yvonne Lefébure.

A long and successful international career followed, blighted only by his behaviour during World War II. Unfortunately, during the German occupation of France, Cortot accepted appointments in the Vichy government and gave concerts in Germany: as a result, he was not popular in France immediately after the war and tried to restart his career in Europe, playing in Britain, Switzerland and Italy in 1946. In January 1947 he played Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor Op. 54 in Paris, not without problems with the orchestra, audience and press; however in October 1949 he returned to the Salle Pleyel in Paris for concerts to mark the centenary of Chopin’s death. He also played in Japan and South America in the early 1950s, and in 1956, with Wilhelm Kempff, Cortot inaugurated a summer course at Positano near Naples. His last concert was given in Prades on 10 July 1958.

Reference is often made to Cortot’s technical inaccuracy, and one eminent British critic dismissed him because he ‘…couldn’t play the notes.’ However, on his second tour of America in 1920 he played all five Beethoven piano concertos in two evenings and Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 3 Op. 30 with the composer present. For the Rachmaninov concerto Stokowski conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra and one reviewer passed a comment rarely heard in conjunction with this work, yet repeatedly used in descriptions of Cortot’s playing: ‘Alfred Cortot explores the spiritual depths of music. In the most genuine and unaffected way he is among the most poetic of pianists.’ In London a few years later Cortot was playing Liszt’s Mephisto-Waltz No. 1 where his ‘…wide range of tone colour and his remarkable leggierissimo playing were heard to great advantage.’

With a musical intellect of the stature of Cortot’s, wrong or missed notes seem irrelevant. References are often made to the fact that Cortot sounded as though he were improvising the music he was playing (a major factor in Liszt’s playing also). He was able to create such a grand vision and architecture in his conceptions of great works that minor irritations such as wrong notes are of little import. A perfect example of this is his recording of Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor. It may not have the adrenalin of Horowitz, but Cortot’s understanding of the structure makes for an organic, naturally-evolving reading of this masterpiece. Cortot also produced many study editions of the major piano repertoire and wrote La musique Française de piano, which was published in three volumes.

Cortot was one of the most prolifically-recorded pianists, re-recording some major works two or three times, and not necessarily just electric re-makes of acoustic recordings. All of Cortot’s recordings were made for HMV/Victor and the first discs were made while he was in America in January of 1919 when he was forty-two. From these sessions come some extraordinary discs including a stunningly delicate étude by Liszt, La Leggierezza, and a technically assured Étude en forme de valse by Saint-Saëns. In fact, Horowitz was so impressed by Cortot’s performance of this work, he asked his advice on the technical aspects of it. Also from this time come vivid interpretations of Albéniz, Debussy and Ravel and some excellent Chopin études. It should be noted that different takes of many of these works were issued. Many of the works recorded at the 1919 sessions were repeated in 1923 but issued under the same catalogue number. All these acoustic recordings (and four unpublished sides) were reissued by Biddulph in a handsome two-disc set in 1993, and many of these early Victor recordings are in excellent sound for their age. In England Cortot made recordings of Schumann, the composer probably closest to his heart. In 1923 he recorded his first version of the Piano Concerto Op. 54 and Carnaval Op. 9, as well as his first recording of Debussy Children’s Corner Suite.

During the electrical era of the 78rpm disc Cortot made a huge number of recordings. The most important of these are major works by Chopin, Schumann, Liszt and Franck. Of Chopin, the 1933–1934 recording of the Études Opp. 10 and 25 and Préludes Op. 28 are his best version; of Schumann there is his Carnaval Op. 9 and Études Symphoniques Op. 13 from 1928–1929, and Papillons Op. 2 and Kinderszenen Op. 15 from 1935. Cortot recorded both the Prélude, Choral et Fugue and the Prélude, Aria et Final of César Franck, the former being one of the best interpretations on disc. In addition to this he made two recordings of the Variations Symphoniques in 1927 and 1934. Cortot’s main Liszt recording is that of the Piano Sonata in B minor, and his version of the Légende depicting St Francis de Paul walking on the waters is also overpowering in its conception and grandeur. Less successful recordings include the Concerto for Left Hand by Ravel and some of the later live recitals that have appeared on certain labels.

A few weeks after World War II ended Cortot was writing to the Gramophone Company in London asking about making discs for them, in particular whether he could finish a recording of the complete works of Chopin that he had begun in France in 1942 for the centenary of Chopin’s death in 1949. Due to his wartime activities they were understandably cautious, but although a new contract was drawn up in 1946, things were very different at the Abbey Road Studios after the war. The old guard of Fred Gaisberg had gone and the new regime was not particularly interested in Cortot. He continued to record for HMV/EMI during the late 1940s and early 1950s but much of what he set down was never published. Of interest from these sessions are some Chopin nocturnes, works that Cortot had not previously recorded, and the Polonaise-Fantaisie, which at the time remained unpublished. Naxos has issued five compact discs of Cortot’s Chopin recordings. However, a recording of Schumann’s Kreisleriana Op. 16 from 28 June 1954 was accidentally published in the first pressings of Philips Great Pianists of the Twentieth Century Series (and quickly withdrawn), and when he was approaching eighty in 1956 Cortot again recorded Chopin’s complete ballades, préludes and études, none of which have been published. He also attempted to record Beethoven’s complete piano sonatas, with the exception of the ‘Hammerklavier’ Op. 106, but practically nothing from these sessions is of a standard to be issued. All these later recordings were on tape, of course, and one of the best from this time is the published version of the first book of Debussy’s préludes issued on a ten-inch LP. Sessions in Japan in December 1952 produced recordings of works which have not otherwise been released in performances by Cortot. These include two of Chopin’s scherzos and Schubert’s Moment Musical in F minor.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).