Tracklist

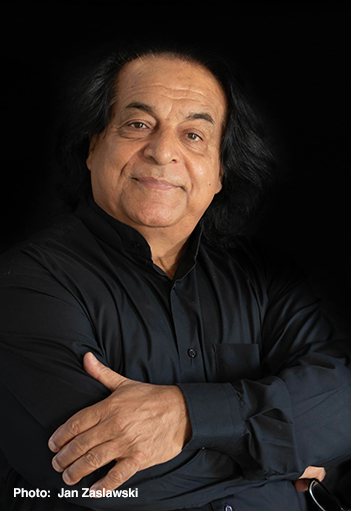

Rahbari, Alexander (Conductor)

Rahbari, Alexander (Conductor)

Rahbari, Alexander (Conductor)

Rahbari, Alexander (Conductor)

Rahbari, Alexander (Conductor)

Rahbari, Alexander (Conductor)

Rahbari, Alexander (Conductor)

Entremont, Philippe (Conductor)

Entremont, Philippe (Conductor)

Entremont, Philippe (Conductor)

Entremont, Philippe (Conductor)

Entremont, Philippe (Conductor)

Philippe Entremont had his first lessons in music from his parents; his father was a conductor of the Strasbourg Opera orchestra, and his mother a pianist and teacher. From the age of eight he studied privately with the retired Marguerite Long, a period of teaching which he found ‘oppressive’, as well as with Rose Aye. At the age of twelve Entremont won the Harriet Cohen International Piano Medal and began lessons at the Paris Conservatoire with Jean Doyen. Whilst at the Paris Conservatoire he won a premier prix for both piano and chamber music. Entremont made his public debut at the age of sixteen in Barcelona while continuing his studies at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1951 he entered the Marguerite Long–Jacques Thibaud International Competition where he won fifth prize and the following year he gained a disappointing tenth placing at the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Belgium. However, a year after that, at the age of nineteen, Entremont won the Marguerite Long–Jacques Thibaud International Competition which led to him being selected to tour America on an exchange programme organised by the Jeunesses Musicales de France. In fact, the first prize at the Marguerite Long–Jacques Thibaud International Competition was not awarded in the piano class of 1953, and Entremont tied for second place with Eugene Malinin.

Entremont made his recital debut in the USA at the National Gallery in Washington, and the following day performed in New York’s Carnegie Hall with the National Orchestral Association and Leon Barzin, giving the American première of the Piano Concerto by André Jolivet. He toured America again in 1955, and in 1956 made his debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy, a partnership that was to prove particularly fruitful. They gave over one hundred concerts together and the best of Entremont’s recordings are with these forces. From the start Entremont was popular in the United States, and the numerous recordings he made for Columbia/CBS helped his career immeasurably.

Although Entremont was building his reputation on the virtuoso Romantic works for piano and orchestra, for his London debut, made at the age of twenty-three, he chose to play Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major Op. 58. He received good reviews, summed up by one critic as, ‘All in all, it was a performance rich in promise.’

Entremont spent the 1960s and 1970s performing and recording, but from the mid-1970s he concentrated more on conducting. He has been guest conductor with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Orchestre National de France, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and many of the other American orchestras. Entremont now performs at many of the summer festivals as a conductor, including the Mostly Mozart Festival at Avery Fisher Hall and those at Santander and Schleswig-Holstein. He has been music director of orchestras in many parts of the world including New Orleans, Israel, Vienna, Denver and Holland.

Entremont spent the 1960s and 1970s performing and recording, but from the mid-1970s he concentrated more on conducting. He has been guest conductor with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Orchestre National de France, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and many of the other American orchestras. Entremont now performs at many of the summer festivals as a conductor, including the Mostly Mozart Festival at Avery Fisher Hall and those at Santander and Schleswig-Holstein. He has been music director of orchestras in many parts of the world including New Orleans, Israel, Vienna, Denver and Holland.

At the beginning of his career Entremont’s repertoire was based around the virtuoso Romantic concertos by composers such as Liszt, Grieg, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev and Saint-Saëns. His American connections also led him to play works by Gershwin, Stravinsky, Bernstein and Jolivet whose Piano Concerto he promoted. Being French, he played a good deal of Satie, Debussy and Ravel, but also Dohnányi, Richard Strauss, César Franck and Bartók. In 1980 he was reported as wishing to play more Schumann, but said, ‘I hate Scriabin – he bores me. I call it “piano music for the deaf!” ’ Throughout his career Entremont has played the music of Mozart, and as early as 1962 played two of the piano concertos in London with Harry Blech and the London Mozart Players.

Entremont recorded a large amount for Columbia from the late 1950s onwards, including much of the solo output of Chopin, Debussy and Ravel. Concerto recordings include the complete piano concertos by Saint-Saëns with the Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse and Michel Plasson made in the late 1970s. Earlier recordings with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy include excellent performances of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concertos No. 1 in F sharp minor Op. 1, No. 4 in G minor Op. 40 and the Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini Op. 43, as well as Saint-Saëns’s Piano Concertos No. 2 in G minor Op. 22 and No. 4 in C minor Op. 44. Less successful are the Liszt concertos, recorded in 1959, where Entremont is rather brash and matter-of-fact, but he has fun with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in their 1967 recording of Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 2. Again with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Entremont recorded Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor Op. 18 and the Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini Op. 43 as well as Bernstein’s own Symphony No. 2 ‘The Age of Anxiety’. Entremont recorded the Piano Concerto by Stravinsky with the composer conducting, and with the Cleveland Orchestra and Pierre Boulez recorded both concertos by Ravel in the early 1970s. From the late 1970s comes an interesting recording of Saint-Saëns’s Le Carnaval des Animaux, where Entremont is joined by pianist Gaby Casadesus and the other instrumental parts are played by soloists with a single cello, viola and two violins forming the string section.

Later recordings show Entremont as conductor, but for Teldec in 1981 he recorded ten piano concertos by Haydn plus two divertimenti for piano and strings with his Vienna Chamber Orchestra.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).

Persian-Austrian conductor and composer Alexander Rahbari studied in Vienna with Hans Swarovsky and Gottfried von Einem. At the age of 23 his violin concerto, Nohe Khan, received the special prize of the Academy of Music in Vienna and was performed in the Vienna Concert Hall. He wrote the following pieces in parallel with his conducting career: Persian Mysticism, Music for Human Rights (Hunger in Africa), Beirut for nine flutes, Half Moon, Musical Sister Angelica Extasy 1 and Mr. Gianni Extasy 2, 154 songs on the complete sonnets of Shakespeare, La Fuerza Flamenca (ten pieces for men’s choir and orchestra) and My Mother Persia.

Having been made chief conductor of the Jeunesses Musicales Orchestra in Teheran at a very young age, he won the Gold Medal at the international conducting competition in Besançon in 1977 and the Silver Medal the following year in Geneva. This led to the start of his international career.

Herbert von Karajan took note of the young artist and invited him to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic as guest conductor in 1979. It was to be the first of a series of such invitations; in 1980 Karajan invited him to be his assistant and substitute at the Salzburg Easter Festival. Rahbari has served as principal guest conductor of the Belgian Radio And Television Philharmonic Orchestra, the Czech Philharmonic and the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra, and music director of the Brussels, Málaga and Zagreb Philharmonic Orchestras, Virtuosi di Praga and the Tehran Symphony Orchestra.

He has conducted over 120 orchestras globally, and has worked with countless acclaimed soloists such as Mischa Maisky, Henryk Szeryng, Mstislav Rostropovitch, Radovan Vlatković, Leonid Kogan, Heinrich Schiff, Nigel Kennedy, Shlomo Mintz, Krystian Zimerman, Radu Lupu, Maurice André and Grace Bumbry.

Born in Hamburg, the son of a double bass player and his older seamstress wife, Brahms attracted the attention of Schumann, to whom he was introduced by the violinist Joachim. After Schumann’s death he maintained a long friendship with the latter’s widow, the pianist Clara Schumann, whose advice he always valued. Brahms eventually settled in Vienna, where to some he seemed the awaited successor to Beethoven. His blend of Classicism in form with a Romantic harmonic idiom made him the champion of those opposed to the musical innovations of Wagner and Liszt. In Vienna he came to occupy a position similar to that once held by Beethoven, his gruff idiosyncrasies tolerated by those who valued his genius.

Orchestral Music

Brahms wrote four symphonies, massive in structure, and all the result of long periods of work and revision. The two early serenades have their own particular charm, while Variations on a Theme by Haydn—in fact the St Anthony Chorale, used by that composer—enjoys enormous popularity, as it illustrates a form of which Brahms had complete mastery. A pair of overtures—the Academic Festival Overture and the Tragic Overture—and arrangements of his Hungarian Dances complete the body of orchestral music without a solo instrument. His concertos consist of two magnificent and demanding piano concertos, a violin concerto and a splendid double concerto for violin and cello.

Chamber Music

Brahms completed some two dozen pieces of chamber music, and almost all of these have some claim on our attention. For violin and piano there are three sonatas, Opp 78, 100 and 108, with a separate Scherzo movement for a collaborative sonata he wrote with Schumann and Dietrich for their friend Joachim. For cello and piano he wrote two fine sonatas: Opp 38 and 99. There are two late sonatas, written in 1894, for clarinet/viola and piano, Op 120, each version deserving attention, as well as the Clarinet Trio, Op 114, for clarinet, cello and piano, and the Clarinet Quintet, Op 115, for clarinet and string quartet, both written three years earlier. In addition to this, mention must be made of the three piano trios, Opp 8, 87 and 101; the Horn Trio, Op 40 for violin, horn and piano; three piano quartets, Opp 25, 26 and 60; the Piano Quintet, Op 34; and three string quartets, Opp 51 and 67. Two string sextets, Opp 18 and 36, and two string quintets, Opp 88 and 111, complete the list.

Piano Music

If all the chamber music of Brahms should be heard, the same may be said of his music for piano. Brahms showed a particular talent for the composition of variations, and this is aptly demonstrated in the famous Variations on a Theme by Handel, Op 24, with which he made his name at first in Vienna, and the ‘Paganini’ Variations, Op 35, based on the theme of the great violinist’s Caprice No. 24. Other sets of variations show similar skill, if not the depth and variety of these major examples of the art. Four Ballades, Op 10, include one based on a real Scottish ballad, Edward, a story of parricide. The three piano sonatas, Opp 1, 2 and 5, relatively early works, are less well known than the later piano pieces, Opp 118 and 119, written in 1892, and the Fantasias, Op 116, of the same year. Music for four hands, either as duets or for two pianos, includes the famous Hungarian Dances (often heard in orchestral and instrumental arrangement) and a variety of original compositions and arrangements of music better known in orchestral form.

Vocal and Choral Music

There is again great difficulty of choice when we approach the large number of songs written by Brahms, which were important additions to the repertoire of German Lied (art song). The Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op 52, for vocal quartet and piano duet are particularly delightful, while the solo songs include the moving Four Serious Songs, Op 121, reflecting preoccupations as his life drew to a close. ‘Wiegenlied’ (‘Cradle Song’) is one of a group of five songs, Op 49; the charming ‘Vergebliches Ständchen’ (‘Vain Serenade’) appears in the later set Five Romances and Songs, Op 84, and there are two particularly wonderful songs for contralto, viola and piano, Op 91: ‘Gestillte Sehnsucht’ (‘Tranquil Yearning’) and the Christmas ‘Geistliches Wiegenlied’ (‘Spiritual Cradle-Song’), Op 91, based on the carol ‘Josef, lieber Josef mein’(‘Joseph dearest, Joseph mine’).

Major choral works by Brahms include the monumental A German Requiem, Op 45, a setting of biblical texts; the Alto Rhapsody, Op 53, with a text derived from Goethe; the Schicksalslied (‘Song of Destiny’), Op 54 (a setting of Hölderlin); and a series of accompanied and unaccompanied choral works, written for the choral groups with which he was concerned in Hamburg and in Vienna.

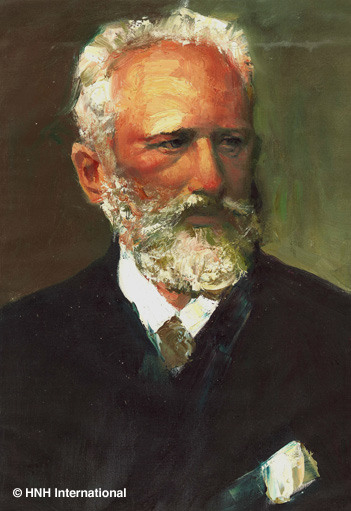

Tchaikovsky was one of the earlier students of the St Petersburg Conservatory established by Anton Rubinstein, completing his studies there to become a member of the teaching staff at the similar institution established in Moscow by Anton Rubinstein’s brother, Nikolay. He was able to withdraw from teaching when a rich widow, Nadezhda von Meck, offered him financial support; this support continued for much of his life, although, according to the original conditions of the pension, they never met. Tchaikovsky was a man of neurotic diffidence, his self-doubt increased by his homosexuality. It has been suggested by some that an impending scandal caused him to take his own life at a time when he was at the height of his powers as a composer, although others have found this improbable. His music is thoroughly Russian in character, but, although he was influenced by Balakirev and the ideals of the Russian nationalist composers ‘The Five’, he may be seen as belonging rather to the more international school of composition fostered by the Conservatories that Balakirev, leader of ‘The Five’, so much deplored.

Operas

Two above all of Tchaikovsky’s operas have retained a place in international repertoire. Eugene Onegin, based on a work by Pushkin, was written in 1877, the year of the composer’s disastrous and brief attempt at marriage. He returned to Pushkin in 1890 with his powerful opera The Queen of Spades.

Ballets

Tchaikovsky, a master of the miniature forms necessary for ballet, succeeded in raising the quality of the music provided for an art that had undergone considerable technical development in 19th-century Russia under the guidance of the French choreographer Marius Petipa. The first of Tchaikovsky’s full-length ballet scores was Swan Lake, completed in 1876, followed in 1889 by The Sleeping Beauty. His last ballet, based on a story by E.T.A. Hoffmann, was The Nutcracker, first staged in St Petersburg in December 1892.

Orchestral Music

Symphonies

Tchaikovsky wrote six symphonies. The First Symphony, sometimes known as ‘Winter Daydreams’, was completed in its first version in 1866 but later revised. No. 2, the so-called ‘Little Russian’, was composed in 1872 but revised eight years later. Of the other symphonies, No. 5, with its motto theme and waltz movement in the place of a scherzo, was written in 1888, while the last completed symphony, known as the ‘Pathétique’, was first performed under Tchaikovsky’s direction shortly before his death in 1893.

Fantasy Overtures and other works

Tchaikovsky turned to literary and dramatic sources for a number of orchestral compositions. Romeo and Juliet, his first fantasy overture after Shakespeare, was written in 1869 and later twice revised. Burya is a symphonic fantasia inspired by The Tempest, and the last of the Shakespearean fantasy overtures, Hamlet, was written in 1888. Francesca da Rimini translates into musical terms the illicit love of Francesca and Paolo, as recounted in Dante’s Inferno, and Manfred, written in 1885, draws inspiration from the poem of that name by Byron. The Voyevoda is described as a symphonic ballad and is based on a poem by Mickiewicz. Other, smaller-scale orchestral compositions include the Serenade for strings, the popular Italian Capriccio, and, rather less well known, four orchestral suites. Tchaikovsky thought little of his 1812 overture, with its patriotic celebration of victory against Napoleon 70 years before, while Marche slave had a topical patriotic purpose. Souvenir de Florence, originally for string sextet, was completed in 1892 in its final version.

Concertos

The first of Tchaikovsky’s three piano concertos has become the most generally popular of all Romantic piano concertos. The second is not so well known, while the third, started in 1893, consists of a single movement, Allegro de concert. Tchaikovsky’s single violin concerto, rejected as being too difficult by the leading violinist in Russia, Leopold Auer, later found a firm place in repertoire. For solo cello Tchaikovsky wrote the Variations on a Rococo Theme and the Pezzo capriccioso. Shorter pieces for violin and orchestra include the Sérénade mélancholique and the Valse-scherzo. Souvenir d’un lieu cher, written as an expression of gratitude for hospitality to Madame von Meck, was originally for violin and piano.

Chamber Music

Tchaikovsky’s chamber music includes three string quartets. The slow movement of the first of these has proved very popular both in its original form and in an arrangement by the composer for cello and string orchestra. The Andante funèbre of the third quartet also exists in an arrangement by the composer for violin and piano.

Piano Music

Tchaikovsky provided a quantity of music for the piano, particularly in the form of shorter pieces suited to the lucrative amateur market. Collections published by the composer include The Seasons, a set of 12 pieces (one for each month), and several sets of pieces with varying degrees of difficulty.

Vocal and Choral Music

Tchaikovsky wrote a considerable quantity of songs and duets, including settings of Goethe’s Mignon songs as well as of less distinguished verse by his contemporaries. His choral works include the 1878 Liturgy of St John Chrysostom and a number of other settings, many of them for unaccompanied voices, of sacred and secular texts.