Not available in the United States due to possible copyright restrictions

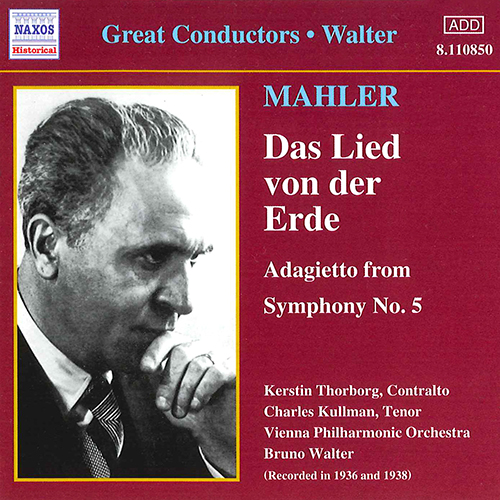

MAHLER: Lied von der Erde (Das) (Walter) (1936-1938)

Mahler composed Das Lied von der Erde in ill health towards the end of his life, and he died before the work’s première took place in 1911, conducted by his close friend Bruno Walter. Incredibly, it took another 25 years before the work was first recorded, once again conducted by Walter, with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, which in 1936 would have included musicians who had played under Mahler himself. Not since this recorded première from 1936 has the sophistication of Mahler’s visionary masterpiece been so closely preserved. To complete the programme Walter conducts the tender Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony, undoubtedly Mahler’s best-loved work.

|

Oops! Something went wrong!

The application has encountered an unhandled error.

Our technical staff have been automatically notified and will be looking into this with the utmost urgency.

|

At the age of nine Lovro von Matačič joined the Vienna Boys’ Choir, remaining a member for three years. He then entered the Vienna Academy of Music, where he studied piano, organ, composition and conducting, and where his teachers included Herbst and Nedbal. His first professional post was that of répétiteur and chorusmaster at the Cologne Opera, where he made his conducting debut in 1919; this was followed by a series of appointments as a conductor in various opera houses in the Balkan states: Osijek (1919–1920), Novi Sad (1920–1922), Ljubljana (1924–1926) and Belgrade (1926–1932). Matačič was first conductor at the Zagreb Opera from 1932 to 1938, the year in which he was appointed chief conductor of the Belgrade Opera and of the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra; during this period he was also a member of the music staff of the Salzburg Festival. He moved to Vienna as a conductor at the Vienna State Opera in1942, remaining there until the collapse of the Axis powers. From this period there exists a sizzling account of the final scene from Richard Strauss’s opera Salome with the Bulgarian soprano Ljuba Welitsch, in which Matačič conducts the Vienna Radio Orchestra.

After the end of World War II he returned to what was now Yugoslavia under the rule of Marshall Tito, playing a significant part in rebuilding musical life there: he helped to found the music festivals at Split and Dubrovnik, and was chief conductor at Skopje. Invited by Walter Legge to record for EMI in 1954, his first recording was of excerpts from Richard Strauss’s Arabella, with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and the Philharmonia Orchestra: a recording which has retained a prominent place in the catalogue for many years. Shortly afterwards he conducted the London Symphony Orchestra both in the studio and in concert in London. In 1956 Matačič succeeded Konwitschny as chief conductor in Dresden and of the Dresden Staatskapelle, and also during this period (1956–1958) shared with him the duties of the post of chief conductor at the Berlin State Opera. He developed a busy career as a guest conductor, appearing at La Scala, Milan, the Rome Opera, the Vienna State Opera, and the Chicago Lyric Opera; in 1959 he conducted a luminous reading of Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Bayreuth Festival. At the Frankfurt Opera he succeeded Solti as chief conductor in 1961, remaining there until 1966, and leading the company in performances of Salome and Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London in 1963. He first appeared in Japan in 1965, later becoming the honorary chief conductor of the NHK Symphony Orchestra of Japanese Radio and Television.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s Matačič made a number of fine operatic recordings for EMI and the German company Eurodisc: these included complete accounts of Puccini’s La fanciulla del West and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci with the forces of La Scala, Milan; Lehár’s Die lustige Witwe with the Philharmonia Orchestra; and Weber’s Der Freischütz and excerpts from Beethoven’s Fidelio, both with the Frankfurt Opera. He returned to Yugoslavia in 1970, holding the post of chief conductor of the Zagreb Philharmonic Orchestra until 1980, and from 1973 to 1979 he was in addition chief conductor of the Monte Carlo Opera Orchestra. At the very end of his life he returned to the podium in London, conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra in a series of concerts which have retained a considerable reputation.

Matačič was a survivor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and of its musical traditions; the soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf commented upon his old-fashioned courtesy, typical of the Hapsburg way of life. As a musician he preferred for instance to conduct Bruckner in the editions that were current at the beginning of the twentieth century, having little time for the scholarship of later eras. A man of considerable size, he brought to his performances a surprising degree of physical vitality, and his interpretations possessed the ebb and flow of tempi that were typical of performances before World War II. His recorded legacy may be most easily divided into studio and live recordings. Matačič’s operatic studio recordings, already mentioned, are uniformly excellent. The early recordings for EMI are all of considerable note, even though at the time of their original release they did not sell well. These include powerful performances of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 4, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade, Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet and the Theme and Variations from the Suite No. 3, as well as numerous shorter pieces from the Russian repertoire. He recorded a notable series of performances with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra for the Supraphon label, including readings of Bruckner’s Symphonies Nos 5 and 7 and of Tchaikovsky’s Symphonies Nos 5 and 6 which certainly represent him at both his best and his most typical stylistically. His few concerto recordings included the Violin Concertos No. 1 of both Bruch and Prokofiev with David Oistrakh, and both Grieg’s and Schumann’s Piano Concerto with Sviatoslav Richter.

Of the many live recordings published, several are outstanding: these include excellent accounts from the Vienna State Opera of Giordano’s Andrea Chénier, with Renata Tebaldi and Franco Corelli, and of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with Sena Jurinac, Anton Dermota and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. A highly characteristic reading of one of Matačič’s ‘signature’ works, Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3, has appeared from his late period with the Philharmonia Orchestra, and a concert of works by Haydn, Schubert and Gottfried von Einem, with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, has also been published. Recordings of Matačič, especially those of live performances, remain important sound documents, containing as they do a style of interpretation characteristic of the earlier part of the twentieth century, which unexpectedly lived on through such recordings until the late years of that century.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).

Richard Strauss enjoyed early success as both conductor and composer, in the second capacity influenced by the work of Wagner. He developed the symphonic poem (or tone poem) to an unrivalled level of expressiveness and after 1900 achieved great success with a series of impressive operas, at first on a grand scale but later tending to a more Classical restraint. His relationship with the National Socialist government in Germany was at times ambiguous, a fact that protected him but led to post-war difficulties and self-imposed exile in Switzerland, from which he returned home to Bavaria only in the year of his death, 1949.

Operas

Richard Strauss created an immediate sensation with his opera Salome, based on the play of that name by Oscar Wilde. Collaboration with Hugo von Hofmannsthal followed, resulting in the operas Elektra and the even more effective Der Rosenkavalier in 1911, followed by Ariadne auf Naxos. Der Rosenkavalier (‘The Knight of the Rose’) remains the best known of the operas of Richard Strauss, familiar from its famous concert waltz sequence. From Salome comes the orchestral ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’, which occurs at an important moment in the drama. The late opera Die Liebe der Danae (‘The Love of Danae’), completed in 1940, may also be known in part from orchestral excerpts. Other operas are Die Frau ohne Schatten (‘The Woman Without a Shadow’), Die ägiptische Helena, Arabella, Intermezzo, Daphne and finally, in 1941, Capriccio.

Orchestral Music

Symphonic Poems

In the decade from 1886 Strauss tackled a series of symphonic poems, starting with the relatively lighthearted Aus Italien (‘From Italy’) and going on to Don Juan, based on the poem by Lenau; the Shakespearean Macbeth; Tod und Verklärung (‘Death and Transfiguration’); Till Eulenspiegel, a study of a medieval prankster; Also sprach Zarathustra (‘Thus Spake Zarathustra’), based on Nietzsche; a series of ‘fantastic variations’ on the theme of Don Quixote; and Ein Heldenleben (‘A Hero’s Life’).

Concertos

Concertos by Strauss include two for the French horn, an instrument with which he was familiar from his father’s eminence as one of the leading players of his time. There is an early violin concerto, but it is the Oboe Concerto of 1945, revised in 1948, that has particularly impressed audiences.

Other Orchestral Works

Strauss wrote various other orchestral works, some derived from incidental music for the theatre, music for public occasions or his operas. The Symphonia domestica and An Alpine Symphony may rank among the symphonic poems, in view of their extra-musical content, while the poignant Metamorphosen for 23 strings, written in 1945, draws inspiration from Goethe in its lament for what has been lost.

Vocal Music

In common with other German composers, Strauss added significantly to the body of German Lieder. Most moving of all, redolent with a kind of autumnal nostalgia that is highly characteristic, are the Vier letzte Lieder (‘Four Last Songs’). He composed songs throughout his life, with a substantial body of such works written in adolescence.

Piano Music

Strauss’s piano music dates principally from his last years at school, illustrating both his precocity and his understanding of the instrument, which then became so apparent in his songs.