Not available in the United States due to possible copyright restrictions

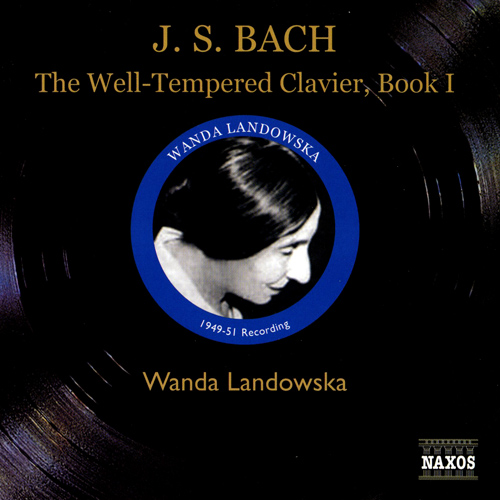

BACH, J.S.: Well-Tempered Clavier (The), Book 1 (Landowska) (1949-1951)

Wanda Landowska, who continued to perform and record up to her death in 1959, was renowned as the greatest harpsichordist of the first half of the twentieth century, resurrecting the instrument and taking a scholarly approach to the performance of music from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This recording of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, made between 1949 and 1954, was begun to commemorate the bicentenary of the death of Bach in 1750. As with all of Landowska’s recordings, what strikes the listener most is her vitality, her musical integrity, and her total commitment to the music she is playing. A contemporary reviewer noted at the time, “All such features of her playing should be studied and pondered, for here is a great musician interpreting in the light of long and fruitful experience and study. Those who know the score best should forget their theories and listen to what she has to say.”

Wanda Landowska came from a cultured background. Her father was an amateur musician and lawyer in Warsaw and her mother, who spoke six languages, was the first to translate the works of Mark Twain into Polish and founded the first Berlitz School in Warsaw. Landowska began to play the piano at the age of four. Her first teacher was Jan Kleczyński and she continued her tuition at the Warsaw Conservatory with Aleksander Michałowski. At seventeen Landowska went to Berlin to complete her studies, in piano with Moritz Moszkowski and in composition with Heinrich Urban.

Having moved to Paris, Landowska married Henri Lew whom she had met in Berlin; he encouraged her to explore music from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. She was introduced to Vincent d’Indy, Charles Bordes and Alexandre Gilmant who founded the Schola Cantorum in order to promote ancient music, as well as to Albert Schweitzer. Between 1905 and 1909 Landowska wrote a number of scholarly articles which were published in book form as Musique Ancienne in 1909. She performed as a pianist, but from 1903 began to appear in public as a harpsichordist, and it is with this instrument that her name is usually connected. Landowska visited Russia twice at this time with her harpsichord and on the second visit played for Leo Tolstoy. She toured throughout Europe as a harpsichordist and just before the outbreak of World War I taught at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin. Landowska and her husband remained in Berlin, but as civil prisoners on parole since they were French citizens. After the war, Landowska taught harpsichord at the Conservatory in Basle for a short period and then returned to Paris, teaching at the Sorbonne and École Normale de Musique. Her husband was killed in a road accident in 1919.

A few years after her first visit to America, which came in 1923 at the invitation of Leopold Stokowski, Landowska founded the École de Musique Ancienne near Paris at Saint-Leu-la-Forêt where she had settled. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s she continued to tour and perform on both the harpsichord and piano, often playing works specially written for her to perform on the harpsichord such as the Concert champêtre by Poulenc and the Concerto by Manuel de Falla. At the Nazi invasion of Paris, Landowska escaped with her pupil and companion Denise Restout whom she had met in 1933. They went first to a town on the Spanish border, then to New York. In 1947 Landowska settled with Restout in Lakeville, Connecticut, and remained there for the rest of her life. She continued to perform into the 1950s and became renowned not only as the most eminent harpsichordist of the first half of the twentieth century, but also as the individual responsible for resurrecting both the instrument and a scholarly approach to the performance of music from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, fashions in performance of music from this period change rapidly, and comparisons of a recording of a work of Bach by Landowska on her custom-built Pleyel harpsichord with a piano recording by Glenn Gould, or even a modern harpsichord performance, show how wide these changes can be. Landowska’s first records were made for Victor during her first visit to America in 1923. She recorded Bach’s Das wohltemperierte Klavier between 1950 and 1954 at her home in Lakeville, completing it at the age of seventy-five. These were recordings where she played the harpsichord. However, Landowska also made recordings on the piano of works by Mozart. The first were made in London for HMV in March 1937, when she was asked to record the ‘Coronation’ Concerto K. 537 in celebration of the coronation of George VI. In this and other Mozart concerto recordings Landowska plays her own cadenzas and applies tasteful decoration. A filler for the last side of the 78rpm set of discs was the Fantasy in D minor K. 397 of which Landowska gives a pure, controlled and exquisite performance. Back in Paris in January 1938 Landowska recorded five of Mozart’s piano sonatas for French HMV. The outbreak of World War II prevented their issue, and apparently the matrices were destroyed, but the recordings of K. 332 in F major, K. 576 in D major and an incomplete K. 311 in D major have been issued on compact disc from surviving test pressings. Landowska always makes the listener aware of the structure of the works by underlining salient structural points. She combines this with a pure tone, exemplary articulation and clarity. The slow movement of the Sonata in F major is a model of taste and distinction with beautifully executed ornaments.

In 1956 Landowska recorded four of Mozart’s piano sonatas, the Rondo in A minor K. 511 and German Dances K. 606 for RCA Victor who took their recording equipment to her home in Lakeville. At the age of eighty, in the spring of 1959 shortly before her death, Landowska recorded Haydn’s Variations in F minor and his Sonatas in E minor and E flat major on the piano as well as some sonatas on the harpsichord.

A few recordings of Landowska in live performances as pianist have appeared, most notably in Mozart’s Piano Concerto in E flat K. 482. It is a broadcast from New York in 1945 when she performed with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and Artur Rodzinski. In the following year the Concerto in C major K. 415 was broadcast with the same forces.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).

Johann Sebastian Bach belonged to a dynasty of musicians. In following inevitable family tradition, he excelled his forebears and contemporaries, although he did not always receive in his own lifetime the respect he deserved. He spent his earlier career principally as an organist, latterly at the court of one of the two ruling Grand Dukes of Weimar. In 1717 he moved to Cöthen as Court Kapellmeister to the young Prince Leopold and in 1723 made his final move to Leipzig, where he was employed as Cantor at the Choir School of St Thomas, with responsibility for music in the five principal city churches. In Leipzig he also eventually took charge of the University Collegium musicum and occupied himself with the collection and publication of many of his earlier compositions. Despite widespread neglect for almost a century after his death, Bach is now regarded as one of the greatest of all composers. Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis numbers, abbreviated to BWV, are generally accepted for convenience of reference.

Choral and Vocal Music

Bach wrote a very large amount of choral music, particularly in connection with his employment at Leipzig. Here, he prepared complete cycles of cantatas for use throughout the church year, in addition to the larger-scale settings of the Latin Mass and the accounts of the Passion from the gospels of St Matthew and of St John. These works include the Mass in B minor, BWV 232, St Matthew Passion, BWV 244, St John Passion, BWV 245, Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248, Easter Oratorio, BWV 249, and the revised setting of the Magnificat, BWV 243. Cantatas include, out of over 200 that survive, Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben, BWV 147 (from which the pianist Dame Myra Hess took her piano arrangement under the title Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, making this the most popular of all), Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80, Ich habe genug, BWV 82, Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 358, Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut, BWV 199, Wachet auf, BWV 140, and Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen, BWV 51, for soprano, trumpet, strings and basso continuo. The rather more formal half dozen or so motets include a memorable version of Psalm CXVII, Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden, BWV 230.

Secular cantatas include the light-hearted Coffee Cantata, BWV 211 (a father’s attempt to stem his daughter’s addiction to the fashionable drink), the Peasant Cantata, BWV 212 (in honour of a newly appointed official), and two wedding cantatas, Weichet nur, BWV 202, and O holder Tag, BWV 210. Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd, BWV 208, was written in 1713 to celebrate the birthday of the hunting Duke Christian of Saxe-Weissenfels and later reworked for the name day of August III, King of Saxony, in the 1740s. The Italian Non sa che sia dolore, BWV 209, apparently marked the departure of a scholar or friend from Leipzig.

Organ Music

Much of Bach’s organ music was written during the earlier part of his career, culminating in the period he spent as court organist at Weimar. Among many well-known compositions we may single out the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue in D minor, BWV 903, the Dorian Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 538, the Toccata, Adagio and Fugue, BWV 564, Fantasia and Fugue in G minor, BWV 542, Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582, Prelude and Fugue “St Anne”, BWV 552 (in which the fugue theme resembles the well-known English hymn of that name), Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565, and the Toccata and Fugue in F, BWV 540.

Chorale preludes are compositions for organ that consist of short variations on simple hymn tunes for all seasons of the church year. Better-known melodies used include the Christmas In dulci jubilo, BWV 608, Puer natus in Bethlehem, BWV 603, the Holy Week Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 625, and the Easter Christ ist erstanden, BWV 627, as well as the moving Durch Adam’s Fall ist ganz verderbt, BWV 637, and the familiar Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 645, and Nun danket alle Gott, BWV 657.

Other Keyboard Music

Important sets of pieces are the six English Suites, BWV 806–11, the six French Suites, BWV 812–17, the ‘Goldberg’ Variations, BWV 988 (written to soothe an insomniac patron), the ‘Italian’ Concerto, BWV 971, the six partitas, BWV 825–30, and the monumental two books of preludes and fugues in all keys, The Well-Tempered Clavier, BWV 846–93—the so-called ‘48’.

Chamber Music

During the period Bach spent at Cöthen he was able to devote his attention more particularly to instrumental composition for solo instruments, for smaller groups or for the small court orchestra.

Particularly important are the three sonatas and three partitas for unaccompanied violin, BWV 1001–6, works that make great technical demands on a player, and the six suites for unaccompanied cello, BWV 1007–12. There are six sonatas for violin and harpsichord, BWV 1014–19, and an interesting group of three sonatas for viola da gamba and harpsichord, sometimes appropriated today by viola players or cellists, BWV 1027–9. The Musical Offering resulted from Bach’s visit in 1747 to the court of Frederick the Great, where his son Carl Philipp Emanuel was employed. From a theme provided by the flautist king he wrote a work that demonstrates his own contrapuntal mastery and includes a trio sonata for flute, violin and continuo. Bach had earlier in his career written a series of flute sonatas, as well as a partita for unaccompanied flute.

Orchestral Music

The six ‘Brandenburg’ Concertos, BWV 1046–51, dedicated to the Margrave of Brandenburg in 1721, feature a variety of forms and groups of instruments, while the four orchestral suites or overtures, BWV 1066–1069, include the famous ‘Air on the G String’, a late-19th-century transcription of the Air from the Suite in D major, BWV 1068.

Concertos

Three of Bach’s violin concertos, written at Cöthen between 1717 and 1723, survive in their original form, with others existing now only in later harpsichord transcriptions. The works in original form are the Concertos in A minor and in E major, BWV 1041 and 1042, and the Double Concerto in D minor for two violins, BWV 1043.

Bach wrote or arranged his harpsichord concertos principally for the use of himself and his sons with the Leipzig University Collegium musicum between 1735 and 1740. These works include eight for a single solo harpsichord and strings, BWV 1052–9, and others for two, three and four harpsichords and strings. It has been possible to provide conjectural reconstructions of lost instrumental concertos from these harpsichord concertos, including a group originally for oboe and the oboe d’amore and one for violin and oboe.