Tracklist

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

Rubinstein, Artur (piano)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

Rubinstein, Artur (piano)

Coates, Albert (Conductor)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

Coates, Albert (Conductor)

Coates, Albert (Conductor)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

Barbirolli, John (Conductor)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

Barbirolli, John (Conductor)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

Rubinstein, Artur (piano)

Rubinstein, Artur (piano)

London Symphony Orchestra (Orchestra)

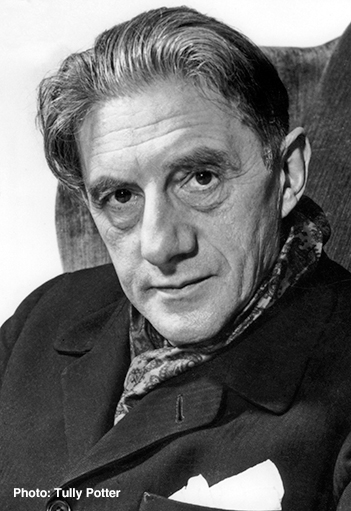

Arthur Rubinstein was the youngest of seven children, the sixth being born eight years before him. His musical talent was evident at a very early age, being musically tested at the age of four at Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik by Joseph Joachim. He was not exploited as a child prodigy, although he gave his first concert at age seven, and after some lessons from local teachers in Łódź and Warsaw returned to Berlin at the age of ten where Joachim supervised his musical training. He studied piano with Heinrich Barth and theory with Max Bruch and Robert Kahn. At twelve Rubinstein made his debut in Berlin playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto in A major K. 488 with Joachim conducting. Over the next few years he continued his education and played concerts in Warsaw, Hamburg and Dresden. The summer of 1903 was spent with Paderewski at his home in Morges and upon his return to Berlin, Rubinstein decided to finish his studies with Barth and go to Paris. His years from ten to seventeen were spent in Berlin, supported by patrons; he hardly ever saw his family.

At his Paris debut Rubinstein played Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor Op. 21 and Saint-Saëns’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor Op. 22 with the Lamoureux Orchestra and Camille Chevillard. Rubinstein was engaged by the Knabe piano company to tour America, giving forty concerts in three months; his debut was in Carnegie Hall where he played Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor Op. 22 with the Philadelphia Orchestra. By this time Rubinstein had already become popular in high society, and practising new repertoire and studying scores took second place to socialising. He relied on his talent to learn quickly, did not work at technically difficult passages and used the sustaining pedal as a camouflage. Reviews in America were not good, mainly commenting that Rubinstein was inexperienced and unprepared, but was clearly a talent that would mature.

Already living beyond his means, Rubinstein gave piano lessons and played orchestral and opera scores to whoever would pay him. He gave concerts in Poland and Russia and was then sponsored by Prince Lubomirski which enabled him to give concerts in Berlin, Rome, Vienna, Kraków and Lwów. In 1912 Rubinstein played Karol Szymanowski’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in Vienna, Leipzig and Berlin and then gave six concerts in London, some with instrumentalists Pablo Casals and Jacques Thibaud. When he returned to England in 1915 Rubinstein gave twenty concerts with violinist Eugène Ysaÿe. Because he spoke at least five languages, during World War I Rubinstein was based in Paris acting as an interpreter. He then toured Spain and South America, where he was extremely popular. This was the beginning of his lifelong association with the music of Spain.

Once the war was over, Rubinstein continued the life of performer and socialite, but after his marriage, at the age of forty-five, he stopped appearing in public because he was not satisfied with his playing, describing himself as ‘an unfinished pianist who played with dash’. He worked on his technique, studied scores in more detail than before and returned to the concert stage with immediate success, continuing a career well into his eighties. Not simply a solo pianist with a large repertoire, Rubinstein also played chamber music with violinist Jascha Heifetz and cellist Emanuel Feuermann (and later with Gregor Piatigorsky). Rubinstein loved to play the piano and would think nothing of performing two concertos in one concert, even when in his seventies. In the mid-1950s he played seventeen works for piano and orchestra in five concerts, and in 1961, already in his mid-seventies, he played ten recitals at Carnegie Hall. He gave his final recital in London’s Wigmore Hall in June 1976 at the age of eighty-seven. He lived on with failing eyesight until the age of ninety-five, completing two volumes of entertaining autobiography entitled My Young Years (1973) and My Many Years (1980).

Rubinstein’s recording career lasted from 1927 to 1976. He recorded much of his repertoire, including the complete works of Chopin, and many other works more than once, including Beethoven’s piano concertos three times. In 1999 RCA/BMG issued his complete authorised recordings on ninety-four compact discs. From the early years come compelling accounts of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor Op. 23 with the London Symphony Orchestra and John Barbirolli made in 1932, and Saint-Saëns’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor Op. 22 with the Orchestre de la Société du Conservatoire and Philippe Gaubert from 1939. The Tchaikovsky is regal and expansive, with drama when needed, but the Saint-Saëns was not issued at the time, perhaps because of a few inaccuracies. It is a wonderfully vibrant and exciting recording of this work, only made available in 1998 by Testament, and then included in the RCA/BMG set. Another highly enjoyable concerto recording is of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major Op. 58, a favourite work of Rubinstein. Made in 1947 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Thomas Beecham it has a buoyancy and character all its own with Rubinstein playing cadenzas by Saint-Saëns.

Rubinstein’s first recording of the complete Chopin mazurkas, made in the late 1930s, has more infectious charm and style than the later recording from the mid-1960s. The 1932 recording of Chopin’s complete scherzos captures Rubinstein before he took himself too seriously, with quicksilver performances caught as if on the wing. Indeed, the 78rpm-era recordings, before editing was possible, are often preferable, as many of the later discs lack a certain spontaneity and sometimes sound as if they were recorded in a vacuum. However, from the LP era comes his greatest recording of Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor Op. 15 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Fritz Reiner made in 1954. Rubinstein had great stage presence, and although there are few live recordings, a Chopin recital given in Moscow in October 1964 captures the excitement of such an event. When RCA/BMG reissued this they unnecessarily tried to patch a slight memory lapse in the Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 35. Rubinstein’s series of ten recitals at New York’s Carnegie Hall in 1961 was recorded, and some of the material was issued. Again, we hear Rubinstein where he preferred to be, in the concert hall with an audience, rather than in the recording studio. Here can be found wonderful performances of works by Debussy, Villa-Lobos, Szymanowski and Schumann.

Of his chamber music recordings, those with violinist Jascha Heifetz and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky are the finest. They were popularly known as The Million Dollar Trio, and their recordings of piano trios by Tchaikovsky, Ravel and Mendelssohn are particularly fine.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — Jonathan Summers (A–Z of Pianists, Naxos 8.558107–10).

The London Symphony Orchestra was established in 1904. It is resident orchestra at the Barbican in the City of London, and reaches international audiences through touring, residencies and digital partnerships. Through a world-leading learning and community program, LSO Discovery, the LSO connects people from all walks of life to the power of great music.

Based at LSO St Luke’s, the Orchestra’s community and music education center and a leading performance venue, LSO Discovery’s reach extends across East London, the UK and the world through both in-person and digital activity.

In 1999, the LSO formed its own recording label, LSO Live, with over 150 recordings released so far. Overall, the LSO has made more recordings than any other orchestra, with 2,500 recordings to its name. The orchestra has collaborated with a genre-busting roster of world-class artists through its work in film, video games and bespoke audio-only experiences.

In addition to entertaining and inspiring millions of listeners, the LSO’s performances have been decorated with multiple honours from the GRAMMY Awards, Oscars, Golden Globes, BAFTAs, and BRITs, not to mention three Mercury Music Prize album nominations.

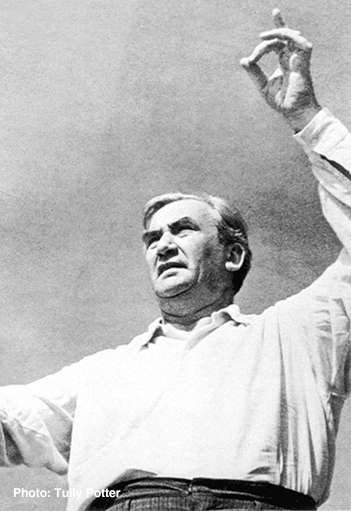

Both John Barbirolli’s father and his grandfather were Italian violinists of note. As members of the orchestra of La Scala, Milan, they had both played in the first performance of Verdi’s Otello (1887), as had Toscanini. Barbirolli’s mother was a native of the southwest region of France. He was born in London and not surprisingly was taught to play music as a very young child. Initially he learnt the violin but at the age of seven he switched to the cello. Three years later he entered Trinity College of Music, transferring after two years to the Royal Academy of Music. His first recordings were made for the Edison Bell Company in 1911, with his sister accompanying him on the piano. He started to play in Sir Henry Wood’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra during 1916, and made his recital debut at the Aeolian Hall the following year. Between 1917 and 1919 he served in the British army, where he had the opportunity to conduct a voluntary orchestra.

On returning to civilian musical life Barbirolli played with many different musical groups, from the London Symphony Orchestra and Sir Thomas Beecham’s Covent Garden Orchestra to cinema and dance bands. He gave the second performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in 1921. Three years later he became a member of the Music Society (later known as the International) and Kutcher String Quartets, both of whom in 1925 and 1926 recorded for the National Gramophonic Society, an early record club run by Sir Compton Mackenzie’s magazine The Gramophone. In 1924 Barbirolli also fulfilled his early ambition to conduct by forming his own chamber orchestra. In 1926 Frederic Austin, the director of the British National Opera Company, invited him to conduct the company on tour, and he made his operatic debut directing Gounod’s Romeo et Juliette at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as well as performances of Aida and Madama Butterfly. He was to conduct the BNOC and Covent Garden Opera Company frequently over the next six years. Also in 1926 Barbirolli deputised at short notice for Beecham, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in a highly-praised performance of Elgar’s Symphony No. 2. It was this performance which brought him to the attention of Fred Gaisberg, of HMV.

In 1927 Barbirolli started to conduct orchestral music for recordings, firstly with the National Gramophonic Society and soon after for the Edison Bell label. In 1928 he commenced his long association with the HMV label, recording a wide range of the shorter pieces that were the staple of the 78rpm record catalogue. He was particularly successful as an accompanist, recording with international instrumentalists of the calibre of Kreisler, Elman, Heifetz, Rubinstein and Backhaus, as well as many singers. In 1933 he took up the post of conductor of the Scottish Orchestra in Glasgow, where he had the opportunity to conduct many major orchestral works for the first time. In addition he conducted the Northern Philharmonic Orchestra, based in Leeds, and appeared as a guest with the newly formed London Philharmonic and BBC Symphony Orchestras as well as with the London Symphony Orchestra.

Mainly as a result of the recommendations of some of the soloists with whom he had recorded, he was offered in 1936 the opportunity to conduct ten concerts over six weeks with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, which had just parted company with Toscanini. So successful were these that Barbirolli was offered the permanent conductorship of the orchestra for a period of three years, starting from the 1937–1938 season. During this time he earned the affection of the players, and audiences initially grew; in addition he made numerous recordings with the orchestra. However Barbirolli’s work in New York was increasingly belittled by critics enamoured of Toscanini, who continued to maintain a presence in the city with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble which had been especially created for the Italian maestro. Barbirolli’s contract was extended for a further two years to 1942, but he was offered only a handful of concerts for the following season, 1942–1943.

In 1942 he had made a hazardous wartime journey to England by sea to conduct the London orchestras, and thus when the invitation came to him to re-form Manchester’s Halle Orchestra in 1943 the time was ripe. Barbirolli immediately accepted and in only one month, through intensive auditioning, he completely re-created the orchestra with which he was to be indissolubly associated for the rest of his life. Initially (between 1943 and 1958) he was the Halle’s permanent conductor, directing it in an exhausting annual schedule of concerts both in Manchester and throughout the British Isles, as well as on tours abroad. Knighted in 1949, in 1958 he reduced his commitment to the orchestra to approximately seventy concerts each year and took the title of conductor-in-chief.

Barbirolli now began to establish a significant international career. He became an annual and respected guest conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, with whom he recorded at the orchestra’s request. Arguably the Berlin orchestra’s mastery of Mahler stems from its work during this period with Barbirolli, rather than from Herbert von Karajan. In 1961 Barbirolli was appointed chief conductor of the Houston Symphony Orchestra in succession to Leopold Stokowski, and stayed with that orchestra until 1967; in addition he toured abroad extensively with the Philharmonia and BBC Symphony Orchestras as well as with the Halle. In 1968 he became conductor laureate of the Halle, but his unremitting schedule of concerts and recordings was by now taking its toll. Barbirolli’s last public concert was given with the Halle Orchestra at the King’s Lynn Festival on 25 July 1970. Four days later he collapsed and died, while rehearsing the Philharmonia Orchestra for a tour of Japan.

Throughout the post-war era and right up to his death Barbirolli was active in the recording studio. He recorded with two main companies: EMI, conducting both the Halle and other orchestras; and during the late 1950s with Pye, again recording extensively with the Halle. Pye produced his first stereophonic recordings. Barbirolli’s discography was very large indeed. Among its highlights are a superlative Madama Butterfly, recorded in Rome with the forces of the Rome Opera; a passionate The Dream of Gerontius; deeply-felt interpretations of the Symphonies Nos 5 and 9 of Mahler (the latter with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra), and of the Symphony No. 2 of Elgar, all on the EMI label. On Pye, of note are his recordings of Elgar’s Enigma Variations and Cello Concerto (with Navarra), and rich interpretations of Dvořak’s last three symphonies, as well as many shorter pieces, several with operatic links. Towards the end of his life he also recorded one of the finest readings in the catalogue of the Symphony No. 2 by Sibelius, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, for the Reader’s Digest organisation.

Barbirolli received no formal training in conducting. His musical response was instinctive and rooted in his experience as a string player. At the same time he was always extremely well prepared and a comparison of his conducting scores with his recorded performances demonstrates that he achieved all that he intended. His interpretations are notable for their spontaneity and lush orchestral tone. If at times he might linger over a particularly attractive phrase, the overall structure of a work remained intact. Barbirolli was not an orchestral disciplinarian: his relationship with his players was comradely. With his audiences he developed a natural bond that remains extraordinarily strong to this day: in the north of England his memory is recalled with an intense fervour. He was without question one of the finest British (and European) conductors of the twentieth century.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).

‘An enormous man, very tall, immensely broad shouldered, immensely genial, but also immensely powerful. One got a sort of radiant heat from him and the excitement he could create for orchestras and choir was simply wonderful’: a vivid description of Albert Coates by fellow-conductor Stanford Robinson. Coates was the seventh and youngest son of a Yorkshire-born Englishman who ran the Russian branch of Thornton Woollen Mills; his mother was the Russian-born daughter of English parents. He studied the cello, violin and organ as a child and received composition lessons from Rimsky-Korsakov; when he was six he unknowingly encountered Tchaikovsky while improvising on the piano at a party to which his mother had taken him and in 1893 he travelled through thick snow to attend Tchaikovsky’s funeral. After these early years in Russia, when Coates was twelve he was sent to school in England, where his first music teacher, Henry Riding, encouraged composition as well as a general love of music. After a year Coates was transferred to another school where one of his brothers was also studying, and where his subjects included the organ, harmony and composition; but when his brother died unexpectedly, the shock was so great that Coates gave up music temporarily and studied science at Liverpool University.

At the age of twenty Coates returned to his family in Russia, with the intention of working in his father’s business. However this was not to his liking and music was more attractive: in the same year he enrolled at the Leipzig Conservatory. Here he studied the cello once more with the Conservatory’s principal Julius Klengel, as well as the piano; and conducting with the charismatic Hungarian Arthur Nikisch, the chief conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and of the Leipzig Opera. Coates’s skill as a pianist was to be a useful introduction to the Leipzig Opera where, after only one year as a conducting student of Nikisch, he was appointed as a répétiteur. Here he made his conducting debut with Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann in 1904, replacing a sick colleague. His success led to many more conducting opportunities during the following two years, and Nikisch, impressed by Coates’s unusually high levels of energy, remarked, ‘The conductor’s stick seems insufficient for your feelings, Coates. You’d better take a whip!’

Nikisch recommended Coates for the post of chief conductor at the Elberfeld Opera, where between 1906 and 1908 he directed the traditional repertoire of opera by Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner and Richard Strauss. He then moved to Dresden, where he was assistant to the legendary Strauss conductor Ernst von Schuch, before progressing on to Mannheim for the following season (1909–1910), where he was first conductor to its chief, Artur Bodansky. Coates made his London debut in 1910, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, and the following year he was invited to conduct Siegfried at the Maryinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. So successful was this debut that he was engaged as a principal conductor at the Maryinsky and stayed there for a further five years. During this period he came into close contact with many major Russian musicians including Scriabin, of whom he was a consistent and energetic champion. He first appeared at Covent Garden during the 1914 season with Tristan und Isolde, and also shared performances of the Ring operas with Nikisch.

The outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917 was to change the direction of Coates’s career in several different ways. Initially the new Soviet government made him ‘President of all Opera Houses in Soviet Russia’ and he was based in Moscow. However by 1919 living conditions had become so bad that most of the orchestral musicians with whom he worked were starving, and some were even too ill to rehearse. Coates himself became seriously ill and with considerable difficulty left Russia with his family by way of Finland. He made his way to England, where the London Symphony Orchestra was seeking a conductor to help in its rebuilding process: its ranks had been severely depleted by war, with concerts even being suspended in 1917. In order to assist, Coates offered to conduct without fee for his initial six concerts with the orchestra, and he was duly appointed as chief conductor, leading all the concerts of the 1919–1920 season. With the LSO he went on to conduct the first performances of the revised version of Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No. 2 ‘London’, Bax’s Symphony No. 1 and the first complete public performance of Holst’s The Planets. Sir Thomas Beecham engaged him as artistic co-director and senior conductor for the first post-war season of the British Opera Company and in 1922 he conducted the Ring at Covent Garden, to be followed by Boris Godunov (1928), Siegfried (1935), and Tristan und Isolde (1937, 1938).

After the 1920–1921 season Coates ceased to be the LSO’s chief conductor but continued to work with the orchestra regularly, not least in the recording studios. After an initial period with Columbia, during which he and the LSO recorded amongst many titles Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy, for three years from the autumn of 1921 he led the orchestra in a number of significant acoustic recordings for HMV, including Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5, as well as excerpts from the Wagner operas. The introduction of the electrical recording process in 1925 rendered these obsolete and also greatly stimulated the demand for recordings in general: Coates and the LSO were well placed to respond. Up until 1932, when Beecham’s new London Philharmonic Orchestra became the preferred ‘house’ orchestra for both HMV and Columbia (these companies having merged to form EMI in 1931), Coates was extremely active in the recording studio, and it is through many of these recordings that he is largely remembered today.

Among the highlights of his extensive recordings from this period are Bach’s B minor Mass, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, Borodin’s Symphony No. 2 and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 3, Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with Horowitz, Stravinsky’s Petrushka, and numerous shorter pieces and operatic excerpts. Coates’s account of the love duet from Act 2 of Tristan und Isolde with Frida Leider and Lauritz Melchior, made in Berlin and London, has been described as unique for its ‘wild, surging, truly overwhelming passion’ (Dr John Barker). Frida Leider herself left a memorable account of this recording: ‘You know both Melchior and I were inspired by Albert Coates, we felt we had achieved one of the greatest performances of this music we ever gave together… and Coates was capable of generating considerable passion. I well remember that after the final note I was so carried away that my head reeled and I had to hold on to Melchior.’

Coates had made his New York debut in 1920 at the invitation of Walter Damrosch, and between 1923 and 1925 he was chief conductor of the Rochester Symphony Orchestra. Throughout the inter-war years he built up a significant international career that included appearances at the Paris Opera (1923), in Italian opera houses (1927 to 1929), at the Berlin State Opera (1931), with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (1935), and at Rotterdam, Stockholm and in the USSR which he visited three times. In 1936 he formed the short-lived British Drama Opera Company to perform his opera Pickwick, which was the first opera to be shown on television. During World War II, Coates was based in the USA, where as well as conducting he wrote the music for several films. After returning to England in 1944 he made several distinguished recordings during 1945 for Decca with the LSO and the National Symphony Orchestra, which contained a high proportion of musicians from the armed forces. Shortly afterwards he retired to South Africa, the home of his second wife, the soprano Vera de Villiers. Here Coates both composed and conducted the Cape Town Municipal Orchestra; he died in Cape Town at the end of 1953.

In general Coates’s recordings, like the man, are suffused with a tremendous sense of vitality. This ideally suited the Russian and Romantic repertoire that he preferred, and gave Coates’s recordings great character in an age when the current technologies of acoustic recording tended often to iron out differences of interpretation. Even today it is rare to encounter performances of the music of Wagner that possess such drive and energy: for instance his recording of the Prelude to Das Rheingold, made in 1926, has been described as one of the finest ever recorded. Occasionally Coates’s enthusiasm resulted in tempi that verged on the manic, for instance in his account of Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 ‘Jupiter’, but in general he served the music that he directed well. The ending of his relationship with HMV in 1932 effectively closed his recording career, but his final post-war Decca recordings show that he had lost none of his ability to realise to the full the great Romantic scores, such as Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 ‘Pathétique’, and where in addition he had the benefit of Decca’s new ‘Full Frequency Range Recording’ system. The gradual ending of copyright restrictions and the growth of interest in the great musicians of the past has done much to rehabilitate Albert Coates as a distinguished musician in the mould of Arthur Nikisch, the mentor for all twentieth-century conductors.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).

Born in Hamburg, the son of a double bass player and his older seamstress wife, Brahms attracted the attention of Schumann, to whom he was introduced by the violinist Joachim. After Schumann’s death he maintained a long friendship with the latter’s widow, the pianist Clara Schumann, whose advice he always valued. Brahms eventually settled in Vienna, where to some he seemed the awaited successor to Beethoven. His blend of Classicism in form with a Romantic harmonic idiom made him the champion of those opposed to the musical innovations of Wagner and Liszt. In Vienna he came to occupy a position similar to that once held by Beethoven, his gruff idiosyncrasies tolerated by those who valued his genius.

Orchestral Music

Brahms wrote four symphonies, massive in structure, and all the result of long periods of work and revision. The two early serenades have their own particular charm, while Variations on a Theme by Haydn—in fact the St Anthony Chorale, used by that composer—enjoys enormous popularity, as it illustrates a form of which Brahms had complete mastery. A pair of overtures—the Academic Festival Overture and the Tragic Overture—and arrangements of his Hungarian Dances complete the body of orchestral music without a solo instrument. His concertos consist of two magnificent and demanding piano concertos, a violin concerto and a splendid double concerto for violin and cello.

Chamber Music

Brahms completed some two dozen pieces of chamber music, and almost all of these have some claim on our attention. For violin and piano there are three sonatas, Opp 78, 100 and 108, with a separate Scherzo movement for a collaborative sonata he wrote with Schumann and Dietrich for their friend Joachim. For cello and piano he wrote two fine sonatas: Opp 38 and 99. There are two late sonatas, written in 1894, for clarinet/viola and piano, Op 120, each version deserving attention, as well as the Clarinet Trio, Op 114, for clarinet, cello and piano, and the Clarinet Quintet, Op 115, for clarinet and string quartet, both written three years earlier. In addition to this, mention must be made of the three piano trios, Opp 8, 87 and 101; the Horn Trio, Op 40 for violin, horn and piano; three piano quartets, Opp 25, 26 and 60; the Piano Quintet, Op 34; and three string quartets, Opp 51 and 67. Two string sextets, Opp 18 and 36, and two string quintets, Opp 88 and 111, complete the list.

Piano Music

If all the chamber music of Brahms should be heard, the same may be said of his music for piano. Brahms showed a particular talent for the composition of variations, and this is aptly demonstrated in the famous Variations on a Theme by Handel, Op 24, with which he made his name at first in Vienna, and the ‘Paganini’ Variations, Op 35, based on the theme of the great violinist’s Caprice No. 24. Other sets of variations show similar skill, if not the depth and variety of these major examples of the art. Four Ballades, Op 10, include one based on a real Scottish ballad, Edward, a story of parricide. The three piano sonatas, Opp 1, 2 and 5, relatively early works, are less well known than the later piano pieces, Opp 118 and 119, written in 1892, and the Fantasias, Op 116, of the same year. Music for four hands, either as duets or for two pianos, includes the famous Hungarian Dances (often heard in orchestral and instrumental arrangement) and a variety of original compositions and arrangements of music better known in orchestral form.

Vocal and Choral Music

There is again great difficulty of choice when we approach the large number of songs written by Brahms, which were important additions to the repertoire of German Lied (art song). The Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op 52, for vocal quartet and piano duet are particularly delightful, while the solo songs include the moving Four Serious Songs, Op 121, reflecting preoccupations as his life drew to a close. ‘Wiegenlied’ (‘Cradle Song’) is one of a group of five songs, Op 49; the charming ‘Vergebliches Ständchen’ (‘Vain Serenade’) appears in the later set Five Romances and Songs, Op 84, and there are two particularly wonderful songs for contralto, viola and piano, Op 91: ‘Gestillte Sehnsucht’ (‘Tranquil Yearning’) and the Christmas ‘Geistliches Wiegenlied’ (‘Spiritual Cradle-Song’), Op 91, based on the carol ‘Josef, lieber Josef mein’(‘Joseph dearest, Joseph mine’).

Major choral works by Brahms include the monumental A German Requiem, Op 45, a setting of biblical texts; the Alto Rhapsody, Op 53, with a text derived from Goethe; the Schicksalslied (‘Song of Destiny’), Op 54 (a setting of Hölderlin); and a series of accompanied and unaccompanied choral works, written for the choral groups with which he was concerned in Hamburg and in Vienna.

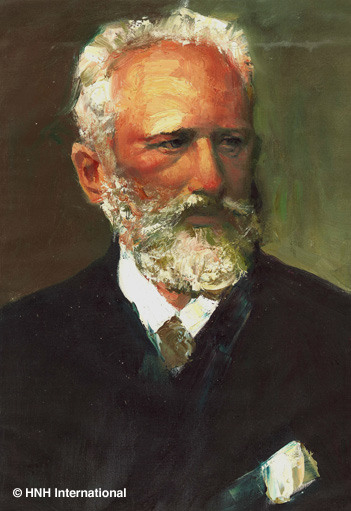

Tchaikovsky was one of the earlier students of the St Petersburg Conservatory established by Anton Rubinstein, completing his studies there to become a member of the teaching staff at the similar institution established in Moscow by Anton Rubinstein’s brother, Nikolay. He was able to withdraw from teaching when a rich widow, Nadezhda von Meck, offered him financial support; this support continued for much of his life, although, according to the original conditions of the pension, they never met. Tchaikovsky was a man of neurotic diffidence, his self-doubt increased by his homosexuality. It has been suggested by some that an impending scandal caused him to take his own life at a time when he was at the height of his powers as a composer, although others have found this improbable. His music is thoroughly Russian in character, but, although he was influenced by Balakirev and the ideals of the Russian nationalist composers ‘The Five’, he may be seen as belonging rather to the more international school of composition fostered by the Conservatories that Balakirev, leader of ‘The Five’, so much deplored.

Operas

Two above all of Tchaikovsky’s operas have retained a place in international repertoire. Eugene Onegin, based on a work by Pushkin, was written in 1877, the year of the composer’s disastrous and brief attempt at marriage. He returned to Pushkin in 1890 with his powerful opera The Queen of Spades.

Ballets

Tchaikovsky, a master of the miniature forms necessary for ballet, succeeded in raising the quality of the music provided for an art that had undergone considerable technical development in 19th-century Russia under the guidance of the French choreographer Marius Petipa. The first of Tchaikovsky’s full-length ballet scores was Swan Lake, completed in 1876, followed in 1889 by The Sleeping Beauty. His last ballet, based on a story by E.T.A. Hoffmann, was The Nutcracker, first staged in St Petersburg in December 1892.

Orchestral Music

Symphonies

Tchaikovsky wrote six symphonies. The First Symphony, sometimes known as ‘Winter Daydreams’, was completed in its first version in 1866 but later revised. No. 2, the so-called ‘Little Russian’, was composed in 1872 but revised eight years later. Of the other symphonies, No. 5, with its motto theme and waltz movement in the place of a scherzo, was written in 1888, while the last completed symphony, known as the ‘Pathétique’, was first performed under Tchaikovsky’s direction shortly before his death in 1893.

Fantasy Overtures and other works

Tchaikovsky turned to literary and dramatic sources for a number of orchestral compositions. Romeo and Juliet, his first fantasy overture after Shakespeare, was written in 1869 and later twice revised. Burya is a symphonic fantasia inspired by The Tempest, and the last of the Shakespearean fantasy overtures, Hamlet, was written in 1888. Francesca da Rimini translates into musical terms the illicit love of Francesca and Paolo, as recounted in Dante’s Inferno, and Manfred, written in 1885, draws inspiration from the poem of that name by Byron. The Voyevoda is described as a symphonic ballad and is based on a poem by Mickiewicz. Other, smaller-scale orchestral compositions include the Serenade for strings, the popular Italian Capriccio, and, rather less well known, four orchestral suites. Tchaikovsky thought little of his 1812 overture, with its patriotic celebration of victory against Napoleon 70 years before, while Marche slave had a topical patriotic purpose. Souvenir de Florence, originally for string sextet, was completed in 1892 in its final version.

Concertos

The first of Tchaikovsky’s three piano concertos has become the most generally popular of all Romantic piano concertos. The second is not so well known, while the third, started in 1893, consists of a single movement, Allegro de concert. Tchaikovsky’s single violin concerto, rejected as being too difficult by the leading violinist in Russia, Leopold Auer, later found a firm place in repertoire. For solo cello Tchaikovsky wrote the Variations on a Rococo Theme and the Pezzo capriccioso. Shorter pieces for violin and orchestra include the Sérénade mélancholique and the Valse-scherzo. Souvenir d’un lieu cher, written as an expression of gratitude for hospitality to Madame von Meck, was originally for violin and piano.

Chamber Music

Tchaikovsky’s chamber music includes three string quartets. The slow movement of the first of these has proved very popular both in its original form and in an arrangement by the composer for cello and string orchestra. The Andante funèbre of the third quartet also exists in an arrangement by the composer for violin and piano.

Piano Music

Tchaikovsky provided a quantity of music for the piano, particularly in the form of shorter pieces suited to the lucrative amateur market. Collections published by the composer include The Seasons, a set of 12 pieces (one for each month), and several sets of pieces with varying degrees of difficulty.

Vocal and Choral Music

Tchaikovsky wrote a considerable quantity of songs and duets, including settings of Goethe’s Mignon songs as well as of less distinguished verse by his contemporaries. His choral works include the 1878 Liturgy of St John Chrysostom and a number of other settings, many of them for unaccompanied voices, of sacred and secular texts.