Not available in the United States, Australia and Singapore due to possible copyright restrictions. Exclusively available for streaming and download. Not available on CD.

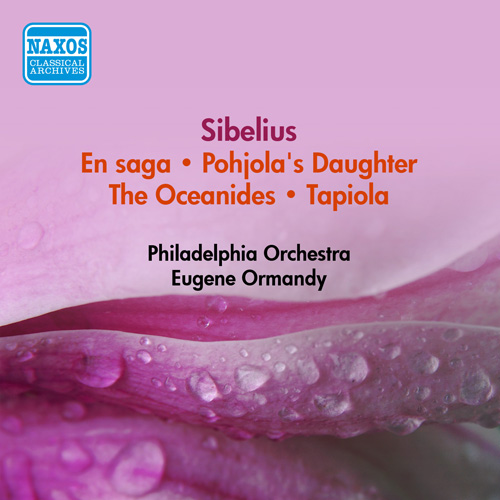

SIBELIUS, J.: Saga (En) / Pohjola's Daughter / The Oceanides / Tapiola (Ormandy) (1955)

Tracklist

Blau, Edouard - Lyricist

Hartmann, Georges - Lyricist

Milliet, Paul - Lyricist

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Colaianni, Domenico (baritone)

Cordella, Salvatore (tenor)

Cappelluti, Gianfranco (baritone)

Voci Bianche Chorus (Choir)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Ramini, Rosita (soprano)

Spina, Gabriele (baritone)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

| 2 | Act I Scene 1: Ma, no, non va … (Bailiff, Children) - Scene 2: Oh come (Johann, Schmidt, Children, Bailiff) - Scene 3: Buon di (Schmidt, Sofia, Johann, Bailiff) - Scene 4: Andiam (Bailiff) | 06:25 |

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Colaianni, Domenico (baritone)

Cordella, Salvatore (tenor)

Cappelluti, Gianfranco (baritone)

Voci Bianche Chorus (Choir)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

| 4 | Act I Scene 4: Oggi Cristo e nato (Children, Werther) - Scene 5: Carlotta! (Children, Carlotta, Bailiff) - Scene 6: Ah, siete (Bailiff, Bruhlmann, Katchen, Carlotta, Werther, Sofia) | 05:28 |

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Colaianni, Domenico (baritone)

Voci Bianche Chorus (Choir)

| 5 | Act I Scene 6: O immagine ideale d'amore e d'innocenza (Werther, Bailiff, Carlotta) - Scene 7: A Bacco viva (Bailiff, Sofia) | 03:06 |

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Colaianni, Domenico (baritone)

Ramini, Rosita (soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Spina, Gabriele (baritone)

Ramini, Rosita (soprano)

| 7 | Act I Scene 10: Lento, calmo, contemplativo - Scene 10: Dividerci dobbiam, signore (Carlotta, Werther) | 03:21 |

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

| 8 | Act I Scene 10: Ma che sapete voi di me? (Carlotta, Werther) - Scene 11: Carlotta … (Bailiff, Carlotta, Werther) | 07:07 |

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Colaianni, Domenico (baritone)

Cappelluti, Gianfranco (baritone)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

| 10 | Act II Scene 2: Così tre mesi gia che uniti siam passar! (Alberto, Carlotta) - Scene 3: Un altro ella sposo (Werther) | 03:45 |

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Spina, Gabriele (baritone)

Cordella, Salvatore (tenor)

Cappelluti, Gianfranco (baritone)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Spina, Gabriele (baritone)

| 13 | Act II Scene 6: Mira, fratel, oh mira il mazzolino! (Sofia, Werther, Alberto) - Scene 8: Ho detto (Werther, Carlotta) | 04:53 |

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Spina, Gabriele (baritone)

Ramini, Rosita (soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

| 14 | Act II Scene 7: Oh, quel soave di dove mai se ne ando (Werther, Carlotta) - Scene 8: Per lei ch'e (Werther) | 06:47 |

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Spina, Gabriele (baritone)

Ramini, Rosita (soprano)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Ramini, Rosita (soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

| 6 | Act III Scene 2: Ah, sorella, no, no! (Sofia, Carlotta) - Scene 3: Ah! Che il coraggio (Carlotta) | 02:25 |

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Ramini, Rosita (soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Spina, Gabriele (baritone)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

Grassi, Luca (baritone)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Voci Bianche Chorus (Choir)

Tufano, Eufemia (mezzo-soprano)

Voci Bianche Chorus (Choir)

Orchestra Internazionale d'Italia (Orchestra)

Tingaud, Jean-Luc (Conductor)

| 18 | Act II: Ma come dopo il nembo so placa il mar fremente (historical recording featuring Mattia Battistini, 1911) | 02:21 |

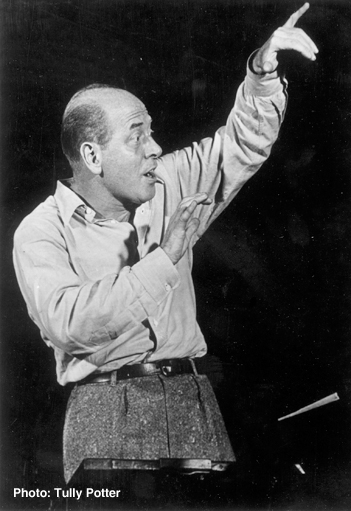

Eugene Ormandy was born Jenő Blau into a musical Jewish family: his father, a dentist, was an amateur violinist, and he named his son after the Hungarian violin virtuoso Jenő Hubay. The boy soon showed signs of musical ability and from an early age was encouraged by his father to practise the violin. He studied at the Royal State Academy of Music in Budapest from the age of five, and with Hubay himself from the age of nine; other teachers included the composers Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály and Leo Weiner. Ormandy was the youngest-ever graduate of the Royal Academy when he received his diploma at the age of fourteen, going on to study philosophy at the University of Budapest from which he graduated when he was twenty, meanwhile also himself teaching at the Royal State Academy of Music from the age of seventeen. During 1917 he toured Hungary and Germany as soloist with the Blüthner Orchestra, and during 1920 France and Austria as a recitalist. Determined to do the same in America, Ormandy arrived there in 1921, only to find that a promised series of concerts had vanished. Down to his last twenty dollars, he auditioned for a place as a violinist in the orchestra of the Capitol Theatre in New York, which showed silent films, and within a year had been promoted to the position of leader of the orchestra. Ormandy’s first experience of conducting came at the Capitol Theatre when in 1924 he substituted for an ailing staff conductor. He continued in this role, for which he clearly had a gift, conducting the same work as often as twenty times in a single week; and became the theatre’s associate music director in 1926, the year in which he became an American citizen, exactly five years and ninety days (the minimum waiting time) after his arrival in the USA. He later remarked in interview that he was ‘…born in New York City at the age of twenty-two’.

Ormandy was spotted at the Capitol Theatre in 1927 by the music agent and orchestral manager Arthur Judson, who took him under his wing and secured guest engagements for him, mainly for radio broadcasts and often for the CBS radio network. During this period Ormandy attended the rehearsals of several of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra’s major conductors, including Mengelberg and Toscanini, and conducted the orchestra himself during 1930 in some of its Lewisohn Stadium concerts. In 1931 he began his association with the Philadelphia Orchestra after Judson booked him as a last-minute replacement for Toscanini, who was incapacitated by bursitis. The unknown conductor proved to be a more than acceptable alternative and as a result he was engaged to substitute for the conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, Henri Verbrugghen, being appointed soon thereafter as that orchestra’s chief conductor. Ormandy proved to be a vigorous programmer of contemporary music: works by composers such as Berg, Krenek, Schoenberg, Shostakovich and Sibelius featured in his programmes. At the same time the unusual orchestral contract then in operation in Minneapolis allowed the orchestra to be recorded at no extra cost, with the result that RCA Victor, which was keen to develop its catalogue of recordings of classical music, recorded Ormandy and the orchestra in an extensive repertoire which featured several of the then-modern works which had appeared in concert performances. These included such pieces as Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht and Sibelius’s Symphony No. 1, as well as large-scale works such as Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 ‘Resurrection’, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7: both the Bruckner and the Schoenberg were receiving their first recordings. Ormandy quickly became one of the most-recorded American conductors of the period, and thereafter proved to be highly conscious of the importance of recordings in maintaining and broadcasting a reputation.

When Leopold Stokowski decided to reduce his commitment to the Philadelphia Orchestra, Ormandy left the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1936 to become co-conductor with him of the Philadelphia; two years later he was appointed as sole chief conductor, remaining in this position until 1980 and touring often within the USA and abroad with the orchestra (for instance to the United Kingdom in 1949, Japan in 1967 and China in 1973). In addition he accepted guest conducting engagements in Europe. After his retirement from the post of chief conductor in 1980 Ormandy was made the Philadelphia’s conductor laureate, a position which he held until his death, marking the hitherto longest unbroken association between a conductor and a major orchestra. His last concert was with the Philadelphia Orchestra at Carnegie Hall on 10 January 1984.

With the Philadelphia Orchestra, Ormandy maintained Stokowski’s emphasis upon richness of tone within the string sections, while gradually returning the orchestra to uniform bowing and traditional seating arrangements in contrast to Stokowski’s enthusiasm for free bowing and experiments with layout. He also developed a more conservative approach to repertoire, which often reflected plans for future recordings. Ormandy continued to record with RCA Victor until 1943, after which both he and the Philadelphia entered into a long-term agreement with the American Columbia label, which lasted until 1968. This relationship proved to be extraordinarily productive and it was through their numerous recordings for Columbia that Ormandy’s international fame and that of the Philadelphia Orchestra was developed and maintained. At the same time the inevitable commercial pressures for numerous popular titles, and Ormandy’s willing acceptance of such repertoire ideas, also created an impression of a conductor whose performances at times lacked insight and depth, preferring surface polish to imagination. Although this impression did contain an element of truth, it was not wholly justified, since by contrast Ormandy programmed a significant amount of contemporary American music, by composers such as Barber, Diamond, Hanson, Piston, Schuman, Sessions and John Vincent, and was quite assiduous in performing recently-edited music such as Deryck Cooke’s completion of Mahler’s Symphony No. 10 and Bogatirev’s of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 7. After 1968 Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra returned to record for RCA Victor, but not so prolifically as had been the case with Columbia. At the very end of his career Ormandy also recorded for several different labels, such as Delos, EMI and Telarc. His discography was vast: it covered much of the late-Romantic orchestral repertoire and reflected his skill as an accompanist. Contained within it were a relatively large number of notable recordings, some of which are listed above.

Ormandy stands within the group of Hungarian conductors who strongly influenced orchestral life during the twentieth century: other notable representatives of this school included Antal Dorati, Fritz Reiner, Georges Sébastian and Georg Solti. Strongly influenced by Bartók and Kodály, all favoured an interpretational approach that emphasised rhythmic drive and orchestral transparency. The major influence was that of Toscanini and its antithesis was Furtwängler. Ormandy was a shrewd observer and had this to say about his and others’ conducting: ‘My conducting is what it is because I was a violinist. Toscanini was always playing the cello, Koussevitzky the double-bass, Stokowski the organ. The conductors who were pianists nearly always have a sharper, more percussive beat, and it can be heard in their orchestras.’

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).

Jean Sibelius grew to maturity at a time of fervent Finnish nationalism, as the country broke away from its earlier Swedish and later Russian overlords. Brought up in a Swedish-speaking family, Sibelius acquired a knowledge of Finnish language and traditional literature at school; early Finnish sagas proved a strong influence on his subsequent work as a composer. After early training in Helsinki and later in Berlin, he made his career in Finland, where he was awarded a state pension. Although he lived until 1957, he wrote little after 1926, feeling out of sympathy with current trends in music.

Stage Works

Sibelius wrote incidental music for Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande, Procopé’s Belshazzar’s Feast and Shakespeare’s The Tempest. His well-known Karelia Suite was derived from incidental music for a pageant. His popular Valse triste was originally written for Järnefelt’s play Death to accompany a deathbed scene.

Orchestral Music

Symphonies

Sibelius wrote seven symphonies, an additional eighth apparently completed but destroyed. The first two of these enjoy particular popularity.

Symphonic Poems etc.

Symphonic poems by Sibelius, their inspiration usually from ancient Finnish legend, include En saga, the Lemminkäinen Suite, of which ‘The Swan of Tuonela’ and ‘Lemminkäinen’s Return’ form a part, Pohjola’s Daughter and Tapiola. Finlandia was adapted from music provided for Press Pension celebrations in 1899.

Concertos

Sibelius was trained as a violinist. His Concerto for the instrument was, however, a technically more demanding work than he could have tackled himself. Sibelius made a revised version, which now has a place in standard solo violin repertoire and still makes considerable demands on the performer.

Chamber Music

Chamber music by Sibelius includes the String Quartet ‘Voces intimae’, a Sonatina for violin, and a number of short pieces for violin and piano.

Piano Music

Although the musical achievement of Sibelius may be regarded as largely orchestral, he did also write a number of shorter piano pieces for which there was always a market.

Songs

Although he wrote some hundred songs over a period of more than 30 years, mainly settings of Swedish texts (eight in German and only a handful in Finnish), they have suffered comparative neglect by the side of his larger-scale orchestral and choral music. Sibelius regarded many of them as representative of his inner self.