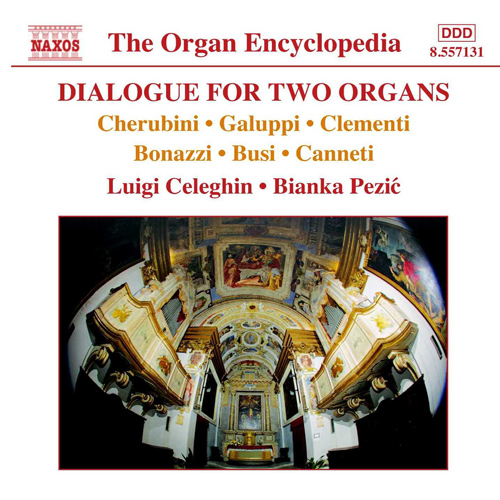

Dialogue for Two Organs

Tracklist

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Devreese, Frederic (Conductor)

Born into a poor Neapolitan family, Caruso was the third of seven children, of whom only three survived infancy. After receiving a basic education he studied technical draftsmanship and at the age of eleven was apprenticed to an engineer who made water fountains. Later he worked with his father, a mechanic and foundry worker, at the Meuricoffre factory in Naples. Meanwhile he sang in his local church choir and in 1889, after the death the year before of his mother, who had encouraged him to pursue his musical ambitions, he began to take singing lessons with Guglielmo Vergine.

To support his family, Caruso worked as a street singer from 1891, also performing in cafes and at soirées. After a short period of military service, completed in 1894, he made his operatic stage debut in 1895 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples, in the opera L’amico Francesco by the amateur composer Domenico Morelli. Further tuition followed with Vincenzo Lombardi, who also taught Antonio Scotti and Pasquale Amato: this improved Caruso’s range and vocal style. He secured engagements in several smaller Italian opera houses, appeared in Cairo in 1896, at Palermo’s Teatro Massimo in 1897 and sang in Russia during the 1897–1898 season.

In 1897 Caruso auditioned for Puccini for the part of Rodolfo / La Bohème in Livorno; after hearing him the composer is reputed to have exclaimed: ‘Who sent you to me? God himself?’ In the same year he created the role of Federico in Cilea’s L’Arlesiana at the Teatro Lirico, Milan. His breakthrough occurred in November 1898 when he sang Loris in the first performance of Giordano’s Fedora, also at the Teatro Lirico, Milan. The composer, who was conducting, left this vivid recollection of the audience response after Caruso’s singing of the aria ‘Amor ti vieta’: ‘The applause was not mere hand clapping, but it seemed to be explosions of passion. The cheers became overwhelming. Caruso encored the aria, as soon as I, surprised by that insistent, intoxicating storm, was able to calm down and start conducting again. The delirium was ecstatic and then there was a second encore and then another. The third act was a crescendo of enthusiasm… Fedora had been consecrated with the new star. Caruso’s voice had conquered everyone’s heart.’

The following year Caruso made his debut at the Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires and in 1900 returned to Russia, where in St Petersburg and Moscow he sang Rodolfo, Edgardo / Lucia di Lammermoor and Riccardo / Un ballo in maschera, opposite the baritone Mattia Battistini. In the same year he first sang at La Scala, Milan, making his debut as Rodolfo, followed by Nemorino / L’elisir d’amore and participation in the Milan premiere of Mascagni’s Le maschere during 1901. By now Caruso was singing in the major Italian opera houses. In June 1902 he created the role of Maurizio in Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, having already created the role of Federico Loewe in Franchetti’s Germania at La Scala in March 1902.

Fred Gaisberg, who had heard Caruso in Germania, engaged him to record ten discs for the young Gramophone Company (then called the Gramophone and Typewriter Company) for the huge (at that time) sum of one hundred pounds. These records rapidly became international best-sellers and swiftly introduced Caruso to London, where he was engaged to sing at the Royal Opera House during the summer of 1902 as the Duke / Rigoletto opposite Nellie Melba, with whom he sang in the same year at Monte Carlo. Other roles in his first season in London included Radamès / Aida and Don Ottavio / Don Giovanni.

Having essayed the title role in Lohengrin (to which he was never to return) in Buenos Aires in 1901, Caruso returned to South America in 1903 to sing in Rio de Janeiro, where he had to encore ‘La donna è mobile’ (Rigoletto) five times. In the autumn of 1903 he sailed to New York to make his first appearance at the Metropolitan Opera, once again as the Rigoletto Duke opposite Marcella Sembrich. As in Milan previously, following popular acclaim he signed an extraordinarily lucrative recording contract, this time with the Victor Company, whereby he was paid royalties on the sales of his recordings. This ensured an enormous income over time for him and his family.

The Met became the centre of Caruso’s operatic work. Here he sang the leading roles of the core Italian and French operatic repertoire, such as Radamès, Cavaradossi / Tosca, Rodolfo, Canio / Pagliacci, Enrico, the Rigoletto Duke, Nemorino, Alfredo / La traviata, Enzo / La Gioconda, Riccardo, Fernando / La favorita, Lionel / Martha (in Italian), Vasco de Gama / L’Africaine (in Italian), Raoul / Les Huguenots, Don José / Carmen and the title role in Gounod’s Faust, all undertaken during his first five seasons at the Met. In addition he sang the leading tenor roles in significant local premieres such as the first American performances of Fedora (1906), Manon Lescaut, Madama Butterfly, Adriana Lecouvreur, Mascagni’s Iris (all 1907) and Gustave Charpentier’s Julien (1914). In 1910 he created the part of Dick Johnson in the world premiere performances of Puccini’s La fanciulla del West. His performance schedules at the Met were extremely heavy and undoubtedly took an eventual toll upon his health: in total he was to sing thirty-seven roles there in over 600 performances.

Alongside his continuing appearances in New York, Caruso remained active in Europe. He made his debut in Germany in 1904 as the Rigoletto Duke at the Berlin Court Opera; sang at Covent Garden between 1904 and 1907 and in 1913 and 1914; at the Paris Opera in 1908 and 1910; with the Metropolitan Opera on tour in 1910 at the Théâtre Châtelet, Paris as des Grieux / Manon Lescaut; and returned to Paris in 1912 with the Monte Carlo Opera. During 1913 he appeared in the major German cities, as well as in Vienna and Prague, and returned to Italy to give benefit performances as Canio in Rome (1914) and Milan (1915).

From 1917 Caruso began to add heavier roles to his repertoire at the Met, notably Samson / Samson et Dalila (1917), John of Leyden / Le Prophète (1918), Don Alvaro / La forza del destino (1918) and Eléazar / La Juive (1919). He continued to sing his existing repertoire and created the role of Flammen in Mascagni’s Lodoletta (1918).

Following an extensive concert tour during 1920 however, Caruso’s wife noticed a decline in his health. He had undergone successful surgery on his vocal chords in 1909, but now he suffered a throat haemorrhage during a performance of L’elisir d’amore at the Met towards the end of 1920. Although the rest of the performance was cancelled, he returned to sing Eléazar, giving what was to be his last public performance on Christmas Eve, 1920. Clearly very unwell, he was eventually diagnosed as suffering from pleurisy and empyema, and underwent a series of operations. He returned to Naples to recuperate but died shortly afterwards, the likely cause of his death being peritonitis arising from a burst subrenal abcess following examination under unhygienic conditions.

The distinguished Italian critic Rodolfo Celletti has suggested that Caruso’s extraordinary success was based upon the unique ‘fusion of a baritone’s full, burnished timbre’ with ‘the tenor’s smooth, silken finish, by turns brilliant and affecting’. This combination allowed for ‘melting sensuality’ and ‘outbursts of fiery, impetuous passion’ in the middle range, as well as ‘clarion brilliance’ in his high notes. Thus his unique sound, allied to his mastery of phrasing and dynamics, enabled him to dominate the performance of Italian and French opera during his lifetime, and for many years afterwards through his recordings. As he himself said: ‘My recordings will be my biography.’

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Singers, Naxos 8.558097-100).

The daughter of a professional baseball player, Geraldine Farrar was strongly supported by her mother in her early desire to be an opera singer. When only fourteen she gave a recital in Boston; and encouraged by Jean de Reszke to pursue her vocal studies she moved to New York where she became a pupil of Emma Thursby. Although quickly offered a contract by the Metropolitan Opera, she and her mother instead left for Paris in 1898 for further study. Here she studied with Trabadello, but balked at Mathilde Marchesi’s traditional approach to operatic singing and acting, searching instead for greater realism. She sought the advice of Lilian Nordica who suggested she approach Lilli Lehmann in Germany.

Farrar and her mother therefore moved to Berlin, where she studied with Graziani. Through an introduction to the intendant of the Berlin Court Opera she was immediately offered a contract to sing there, making her debut as Marguerite / Faust in 1901. This was quickly followed by Violetta / La traviata, after which she was accorded star status. Further roles included Nedda / Pagliacci, Zerlina / Don Giovanni, Juliette / Roméo et Juliette, Elisabeth / Tannhäuser (1905, her only Wagnerian role) and the title role in Massenet’s Manon. In 1903 Lehmann agreed to take Farrar as a pupil, training her to express emotions through her eyes and face rather than by means of extravagant gestures.

Using Berlin as a springboard for her European career, Farrar appeared at Monte Carlo for three seasons from 1904. Here she first sang in La Bohème (1904) with Caruso, with whom she was to form a close artistic partnership, and replaced Calvé at short notice in the world premiere of Mascagni’s Amica (1905). Next she triumphed in Stockholm, Paris, Munich and Warsaw, before returning to America, where in 1906 she made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera, New York as Juliette.

During her sixteen-year reign at the Met Farrar gave more than 600 performances of thirty-four roles across twenty-nine operas, receiving higher fees and appearing in more first performances than any other rival soprano. Notable highlights included the title roles in the first Metropolitan Opera performances of Madama Butterfly (1907), Wolf-Ferrari’s Il segreto di Susanna (1911), Mascagni’s Lodoletta (1918) and Leoncavallo’s Zazà (1920), the Goose Girl in the first performance of Humperdinck’s Königskinder (1910) and the title roles in the world premieres of Giordano’s Madame Sans-Gêne (1915) and Puccini’s Suor Angelica (1918). Popular roles included the title parts in Carmen, Manon, Mignon, Thaïs and Tosca, as well as Cherubino / Le nozze di Figaro, Gilda / Rigoletto, and Zerlina. Farrar’s powerful stage presence and vivid acting won her numerous fans.

In 1922, by which time she was experiencing considerable vocal difficulties through over-work, Farrar gave her farewell performance at the Met as Zazà. However she continued to sing in concerts and recitals for a further ten years, making her final appearance in recital at Carnegie Hall in 1931.

She travelled widely and hosted the intermissions for the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts of the 1934–1935 season. Alongside her operatic work, Farrar also appeared in several silent films made between 1915 and 1920, including the title role in Cecil B. De Mille’s adaptation of Carmen (1915) and Joan of Arc in Joan the Woman (1917).

An artist of iron determination, driven by a greater interest in the emotional rather than the lyrical character of opera, Farrar worked with singers of the calibre of Amato, Caruso, Chaliapin, Eames, Lehmann, Martinelli and Stracciari, as well as with major conductors including Muck, Mahler, Richard Strauss and Toscanini. She recorded throughout her career, in Berlin for the Gramophone Company and later in America for Victor, who featured her extensively in their advertisements. However her recordings cannot give a complete idea of the extent of her very considerable art.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Singers, Naxos 8.558097-100).

Marcel Journet probably studied at the Paris Conservatoire for a short period, before studying singing privately with a teacher named Seghettini in Paris. The start of his operatic career is similarly obscure. While he may have made his stage debut at Béziers in 1891 or at Montpellier in 1893, he certainly first appeared at the Brussels opera house, La Monnaie, in 1894 and remained there until 1899, singing roles in traditional repertoire such as Samson et Dalila, Roméo et Juliette, Sigurd, Fidelio, Lohengrin, Faust and L’Africaine. In 1898 he sang Fasolt in the local premiere of Das Rheingold.

Between 1900 and 1907, Journet was a member of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, singing secondary bass roles while major parts were taken by rivals Édouard de Reszke and Pol Plançon. When these stalwarts retired, to be replaced not by Journet but by Chaliapin, who arrived to acclaim in 1907, Journet diplomatically departed. Similarly, at the Royal Opera House, London where Journet sang from 1897 until 1907 and then 1909, the major bass roles were often shared with de Reszke and Plançon and from 1905 with Vanni Marcoux. Journet’s repertoire in London was typical of the period: it included Italian operas such as Il barbiere di Siviglia, La Bohème, La Gioconda, Loreley, Lucia di Lammermoor and Rigoletto; French operas such as Carmen, Faust, Henry VIII, Les Huguenots, Manon, Messaline, La Navarraise, Philémon et Baucis and Roméo et Juliette, as well as Don Giovanni, Eugene Onegin, Tannhäuser and d’Erlanger’s Inès Mendo.

Journet finally made his debut at the Paris Opera in 1908 (as the King / Lohengrin), appearing in every subsequent season up to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. In Paris he was notably active in German opera, singing Hunding / Die Walküre and Fafner / Das Rheingold (1909), Wotan / Die Walküre (1910), Pogner / Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1911) and Klingsor / Parsifal (1914). During this period he was also a busy concert singer in Paris.

Between 1914 and 1920, Journet reigned supreme at the Monte Carlo Opera, where he appeared in a large repertoire, the highlights of which included Parsifal (Gurnemanz), La Vivandière, Aida, Rigoletto, Lucia di Lammermoor, Samson et Dalila, La Bohème, Ernani, Il barbiere di Siviglia, Platée, Manon, Saint-Saëns’s Étienne Marcel, Gunsbourg’s Maître Manole and Marchetti’s Ruy Blas as well as, unexpectedly and towards the end of this period, the baritone roles of Tonio / Pagliacci and Scarpia / Tosca. Victor Girard has suggested that during World War I Journet restudied his voice so as to completely integrate his three registers, thus giving himself an unexpected top register that enabled him to sing roles such as the latter two.

The benefit of this development was certainly seen in Journet’s subsequent career at La Scala, Milan where he was first bass from 1917 until 1928 and enjoyed the favour of Toscanini, with whom he sang Hans Sachs / Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg in 1922, 1925 and 1928. Other operas in which he appeared here included Lucrezia Borgia, Louise (the Father), Faust (Méphistophélès), Pelléas et Mélisande (Golaud), Carmen (Escamillo) and Khovanshchina (Dosifey). He created the role of Simon Mago in Boito’s Nerone at its premiere in1924 and repeated this role in 1926 and in 1927, all under Toscanini.

Journet returned to Covent Garden in 1927 and 1928 to appear in Carmen and Louise and sang several major roles at the Paris Opera between 1928 and 1930 including Wotan / Siegfried and Hagen / Götterdämmerung. He took major parts in the first Paris performances of Rabaud’s Mârouf (1928) and in two world premieres: Silvio Lazzari’s Le Tour de feu (1928) and Brunel’s La Tentation de St Antoine (1930). He was also active singing in other major opera houses, for instance those of Buenos Aires, Chicago, Madrid and Barcelona.

After 1930 Journet continued to record occasionally but appeared less frequently on stage, although his final appearance was at the Paris Opera as Wotan in 1933, prior to his unexpected death at the health spa of Vittel. He recorded prolifically and as, most unusually, his voice improved with age, his later electrical recordings are among his best. His voice has often been compared to a rare vintage wine that improves with age: certainly on record it has an undeniable attractiveness.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Singers, Naxos 8.558097-100).