|

Oops! Something went wrong!

The application has encountered an unhandled error.

Our technical staff have been automatically notified and will be looking into this with the utmost urgency.

|

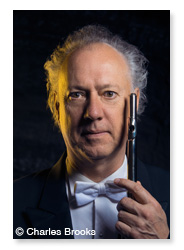

Uwe Grodd, New Zealand based German conductor and flautist, has performed and recorded internationally for over 25 years.

Uwe Grodd first gained worldwide recognition when he won First Prize at the Cannes Classical Awards 2000, for the ‘Best 18th Century Orchestral Recording’ with his CD of Symphonies by Johann Baptist Vaňhal conducting the Nicolaus Esterházy Sinfonia in Hungary. This was followed by a recording of Ignaz Pleyel’s Symphonies with the Capella Istropolitana from Slovakia. In 2002, this CD was one of three finalists in the Best 18th & 19th Century Orchestral Recording category at Cannes. It also reached the Critics’ Choice TOP 60 Discs of the recording year in the BBC Music Magazine.

His world première recording of the Missa Solemnis, by J.N. Hummel, with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and Tower Voices NZ, was voted Editor’s Choice by Gramophone magazine in May 2004.

2006–08 was a very creative and exciting season for Uwe. In less than two years and across four countries, he has produced seven different recordings for Naxos Records: four CDs as a conductor and three as a flautist, performing his own editions of quartets for flute and strings by Johann Baptist Vaňhal and a disc of flute music by Schubert which was released in January 2009. In addition to the many concerts and recordings Uwe was invited to take up the position as Music Director in July 2008 of New Zealand’s longest established choir, the Auckland Choral Society.

This period also marks the halfway point on the journey towards the complete recordings of the works for piano and orchestra by Beethoven’s longstanding friend and student, Ferdinand Ries. Uwe conducted volume three with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and volume four with the Bournemouth Symphony in June 2008 including a remarkable set of variations to ‘Rule Britannia’ for piano and orchestra.

Following the success of Ries’ Volume One, the second in this series of world première recordings was made in Sweden with the Gävle Symphony Orchestra and the same team of Grodd and Hinterhuber, which includes ‘Swedish National Airs and Variations’.

“Hinterhuber and Grodd are the ideal team for Ries’ (1784–1838) music…What an exciting start to this series!” Piano News (February 2006).

Uwe has made other interesting discoveries: previously unheard music by Johann Nepomuk Hummel and, in September 2006, music by the ‘Swedish Mozart’, Joseph Martin Kraus. Uwe Grodd and Takako Nishizaki, with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, recorded his violin concerto as well as the orchestral ballet score to Azire and the Incidental Music for Olympie.

Performance highlights in recent years include the final concerts of the 53rd and the 54th Handel Festival in Halle, Germany. This prestigious event—a televised open-air concert—involves a combined choir of 280 and the State Philharmonic Orchestra. The previous year Uwe conducted the gala opening night of the Halle Handel Festival with Le Choeur des Musiciens du Louvre from Grenoble, a number of front-line soloists and the Halle Opera Orchestra performing on original instruments. This was followed, in 2003 and 2004, by a highly successful season in the Halle Opera House of Handel’s recently re-discovered opera, Imeneo. The season marked the launch of a new performing edition, by Bärenreiter, the foremost European publishing house. The reputable German opera magazine, Opernwelt, nominated the performances as the ‘Rediscovery of the Year 2003’.

Uwe made his Mexican debut in March 2004, with the Mexico City Philharmonic, conducting Beethoven’s 1st Symphony, Liszt’s Mazeppa and Dvořák’s Czech Suite. This was followed by an immediate return invitation in June to conduct Bruckner’s Fourth and Mozart’s ‘Elvira Madigan’ Concerto. Subsequently, Uwe conducted a further eight concerts which included Ein Heldenleben by Richard Strauss, Beethoven’s and Schubert’s Fifth Symphonies and Haydn’s Sinfonia Concertante.

Other highlights have included the opening concerts of the Thüringen Philharmonic’s 2005/2006 season, in Gotha and Suhl, Germany, performing Schumann, Beethoven and Tchaikovsky. In the same month he appeared in the Auckland Town Hall, New Zealand, performing, with the Auckland University Symphony Orchestra, a programme entitled ‘Landscapes’, that included Copland’s Appalachian Spring, Douglas Lilburn’s Songs of Islands and Tchaikovsky’s symphony Winter Daydreams.

From 1998 until 2002, Uwe was Artistic Director of the International Music Festival New Zealand and has been conductor and Music Director of the Auckland University Symphony Orchestra from 1989–2004. In 1989, before an audience of 250,000, he appeared in Symphony Under the Stars with the Auckland Philharmonia.

In 1993 he was appointed Music Director of the Manukau Symphony Orchestra. In 2005, for the opening celebration of the new concert hall—the Genesis Energy Theatre—in Manukau City, a ceremony led by New Zealand’s Prime Minister, he combined five choirs with the MSO in a special project named "The Genesis". It included a world première for choir and orchestra, The Journey, written especially for Uwe Grodd and the MSO by Leonie Holmes.

An avid supporter of contemporary music of all genres, Uwe has been central to numerous commissions and given many first performances including, in 2002, conducting the premier season of the multi-media opera Galileo, with music by John Rimmer and libretto by Witi Ihimaera.

Uwe Grodd is the Founder and Artistic Director of the Flute Fest New Zealand (2001–2004), and an Associate Professor of Conducting and Flute at the University of Auckland. His reputation as an inspiring teacher is well documented by his students’ international performances and prizes. His editions of music by Vaňhal, Beethoven and Ries, published by Artaria Editions, are increasingly in demand.

A graduate of Mainz University, Germany, Uwe Grodd studied with teachers of international repute, including Manfred Schreier, André Jaunet and Werner Peschke. He attributes his major musical growth to the guidance of two of Europe’s finest musicians: Robert Aitken and Maestro Sergiu Celibidache.

For Uwe Grodd, conducting, a solo career, chamber music, teaching and music editing are complementary disciplines. Every aspect of music-making, each musical engagement, every activity makes a vital contribution to the development of the whole musician; and to the fascinating complexity of musical interpretation, that magical process of discovery that is a distillation of rigour and imaginative intuition. Uwe remarks: ‘And during the 18th century one would also have composed, and even made one’s own instruments! I hope that you will find my many different activities on these web pages stimulating and interesting.’

For more information, visit uwegrodd.com.

One of the most creative and versatile musicians of his generation, German-born Friedemann Eichhorn’s artistic activities range from performing early Baroque music on period instruments to classical and contemporary works with renowned orchestras and chamber music partners. Recent highlights include performances with the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Christoph Eschenbach, and the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia under Sir Antonio Pappano. Among many other works, Friedemann Eichhorn rediscovered and first recorded the complete violin concertos of French virtuoso Pierre Rode. He has also given the world premieres of Fazıl Say’s Violin Concerto No. 2, Violin Sonata No. 2 and Tristan und Isolde transcriptions.

Eichhorn is a founding member of the Gropius Quartett and the Phaeton Piano Trio. He studied with Valery Gradow at the University of Music and Performing Arts Mannheim, with Alberto Lysy at the International Menuhin Music Academy and with Margaret Pardee at The Juilliard School, and earned a PhD in musicology from the University of Mainz. Eichhorn holds a violin professorship at the University of Music Franz Liszt Weimar and is artistic director of the Kronberg Academy. He plays the ‘ex-Huberman’ violin by Jean Baptiste Vuillaume from 1856.

Austrian cellist Martin Rummel is far more than only a cellist: “Musician, cultural manager, academic, enjoying life”, is how he describes himself, albeit that playing the cello remains his “core business”. A growing number (currently more than 70) albums for various international labels result in ongoing praise from international press and audiences as well as his reputation as one of the leading cellists of his generation. Numerous premiere recordings and musical rediscoveries testify for Rummel’s belief that content is more important than packaging. “The big task for the next generation is to finally throw out the tuxedo, to focus on what and how music is made rather than on who plays where”, he says.

Martin Rummel is a regular guest of orchestras, festivals and venues across Europe, Asia, Oceania and the Americas, with conductors and chamber music partners of all generations. As a pedagogue, he has published a series of editions of all major cello etudes for Bärenreiter which have become standard worldwide. From 2015 to 2020, he was the Head of School at the University of Auckland’s School of Music and an honorary professor at the China Conservatory of Music. After one year as the CEO of Jam Music Lab, Europe’s only music university specialising in jazz and popular music, he has been President of the Anton Bruckner University in Linz since 2021. Being a passionate music communicator, he is a Founding Partner of HNE Rights (with five record labels and a publishing division), had his own radio shows since 2007, and writes and talks about music in many different formats.

Rummel is an alumnus of the Brucknerkonservatorium Linz and the Cologne Musikhochschule. His heart lies in a playing tradition that was conveyed to him during a decade of studies with the legendary William Pleeth, always focusing on the music, not the musician.

First Prize winner of the prestigious Concours de Genève in 2001, Roland Krüger has performed in venues such as the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels and the Kölner Philharmonie, and at the Schleswig-Holstein Musik, the Rheingau Musik and the Ravello festivals.

As a soloist, he has worked with the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, the Orchestre National de Belgique and the NDR Radiophilharmonie Hannover among others, with conductors such as Fabio Luisi, Eiji Oue and Marc Soustrot.

Krüger studied with Oleg Maisenberg and Karl-Heinz Kämmerling, and from 1999 to 2001 was one of a select group of students to study with Krystian Zimerman in Basel, Switzerland.

He has released albums on Ars Musici and paladino music, and recorded Merk’s cello works with Martin Rummel, and Hummel’s arrangements of Mozart’s Symphonies Nos. 35, 36 and 41 (8.572842) and Nos. 38–40 (8.572841) for Naxos. In 2007 Krüger became a professor at the Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover, and many of his students have been awarded prizes at prestigious competitions.

The youngest child and only surviving son of Leopold Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus was born in Salzburg in 1756, the publication year of his father’s influential treatise on violin playing. He showed early precocity both as a keyboard player and violinist, and soon turned his hand to composition. His obvious gifts were developed, along with those of his elder sister, under his father’s tutelage, and the family, through the indulgence of their then patron, the Archbishop of Salzburg, was able to travel abroad—specifically between 1763 and 1766, to Paris and to London. A series of other journeys followed, with important operatic commissions in Italy between 1771 and 1773. The following period proved disappointing to both father and son as the young Mozart grew to manhood and was irked by the lack of opportunity and lack of appreciation for his gifts in Salzburg, where a new archbishop was less sympathetic. A visit to Munich, Mannheim and Paris in 1777 and 1778 brought no substantial offer of other employment and by early 1779 Mozart was reinstated in Salzburg, now as court organist. Early in 1781 he had a commissioned opera, Idomeneo, staged in Munich for the Elector of Bavaria, and dissatisfaction after being summoned to attend his patron the Archbishop in Vienna led to his dismissal. Mozart spent the last 10 years of his life in precarious independence in Vienna, his material situation not improved by a marriage imprudent for one in his circumstances. Initial success with German and then Italian opera and a series of subscription concerts were followed by financial difficulties. In 1791 things seemed to have taken a turn for the better, despite a lack of interest from the successor to the Emperor Joseph II, who had died in 1790. In late November, however, Mozart became seriously ill and died in the small hours of 5 December. Mozart’s compositions were catalogued in the 19th century by Köchel, and they are now generally distinguished by the K. numbering from this catalogue.

Operas

Mozart was essentially an operatic composer, although Salzburg offered him no real opportunity to exercise his talents in this direction. The greater stage works belong to the last decade of his life, starting with Idomeneo in Munich in January 1781. In Vienna, where he then settled, his first success came with the German opera or Singspiel Die Entführung aus dem Serail (‘The Abduction from the Seraglio’), a work on a Turkish theme, staged at the Burgtheater in 1782. Le nozze di Figaro (‘The Marriage of Figaro’), an Italian comic opera with a libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte based on the controversial play by Beaumarchais, was staged at the same theatre in 1786, followed by Don Giovanni, with a libretto again by Da Ponte, in Prague in 1787. Così fan tutte (‘All Women Behave Alike’) was staged briefly in Vienna in 1790, its run curtailed by the death of the Emperor. La clemenza di Tito (‘The Clemency of Titus’) was written for the coronation of the new Emperor in Prague in 1791, no such commission having been granted Mozart in Vienna. His last stage work in order of performance, a Singspiel, was Die Zauberflöte (‘The Magic Flute’), mounted at the end of September at the Theater auf der Wieden, a magic opera that was running with success at the time of the composer’s death.

Church Music

As he lay dying, Mozart was joined by his friends to sing through parts of a work that he left unfinished. This was his setting of the Requiem Mass, commissioned by an anonymous nobleman who had intended to pass off the work as his own. The Requiem was later completed by Mozart’s pupil Süssmayr, to whom it was eventually entrusted, although other possible completions of the work have since been proposed. Mozart composed other church music, primarily for use in Salzburg. Settings of the Mass include the ‘Coronation’ Mass of 1779, one of a number of liturgical settings of this kind. In addition to settings of litanies and Vespers, Mozart wrote a number of shorter works for church use. These include the well-known Exsultate, jubilate written for the castrato Rauzzini in Milan in 1773 and the simple four-part setting of the Ave verum, written to oblige a priest in Baden in June 1791. Mozart’s Church or Epistle Sonatas were written to bridge the liturgical gap between the singing of the Epistle and the singing of the Gospel at Mass. Composed in Salzburg during a period from 1772 until 1780, the sonatas are generally scored for two violins, bass instrument and organ, although three of them, intended for days of greater ceremony, involve a slightly larger ensemble.

Vocal and Choral Music

In addition to a smaller number of works for vocal ensemble, Mozart wrote concert arias and scenes, some of them for insertion into operas by others. Songs, with piano accompaniment, include a setting of Goethe’s ‘Das Veilchen’(‘The Violet’).

Orchestral Music

Symphonies

Mozart wrote his first symphony in London in 1764–5 and his last in Vienna in August 1788. The last three symphonies, Nos. 39, 40 and 41, were all written during the summer of 1788, each with its own highly individual character. No. 39, in E flat major, using clarinets instead of the usual pair of oboes, has a timbre all its own, while No. 40 in G minor, with its ominous and dramatic opening, is now very familiar. The last symphony, nicknamed in later years the ‘Jupiter’ Symphony, has a fugal last movement, a contrapuntal development of what was becoming standard symphonic practice. All the symphonies, of course, repay listening. Of particular beauty are Symphony No. 29, scored for the then usual pairs of oboes and French horns with strings, written in 1774; the more grandiose ‘Paris’ Symphony, No. 31, written in 1778 with a French audience in mind; and the ‘Haffner’, the ‘Linz’ and the ‘Prague’, Nos. 35, 36 and 38. The so-called ‘Salzburg’ symphonies, scored only for strings and in three movements, on the Italian model, were probably intended for occasional use during one of Mozart’s Italian journeys. They are more generally known in English as Divertimenti, K. 136, 137 and 138. The symphonies are not numbered absolutely in chronological order of composition, but Nos. 35 to 41 were written in Vienna in the 1780s and Nos. 14 to 30 in Salzburg in the 1770s.

Cassations, Divertimenti and Serenades

The best-known serenade of all is Eine kleine Nachtmusik (‘A Little Night Music’), a charming piece of which four of the five original movements survive. It is scored for solo strings and was written in the summer of 1787, the year of the opera Don Giovanni and of the death of the composer’s father. The Serenata notturna, written in 1776 in Salzburg, uses solo and orchestral strings and timpani, while the Divertimento, K. 247, ‘Lodron Night Music’, dating from the same year, also served a social purpose during evening entertainments in Salzburg. Cassations, the word more or less synonymous with divertimento or serenade, again had occasional use—sometimes as street serenades, as in the case of Mozart’s three surviving works of this title, which were designed to mark end-of-year university celebrations. Generally music of this kind consisted of several short movements. Other examples of the form by Mozart include the so-called ‘Posthorn’ Serenade, K. 320, which uses the posthorn itself during its course, and the ‘Haffner’ Serenade, designed to celebrate an event in the Haffner family in Salzburg. The Serenade, K. 361, known as the ‘Gran Partita’, was written during the composer’s first years of independence in Vienna and scored for a dozen wind instruments and a double bass.

Dance Music

Mozart wrote a great deal of dance music both in Salzburg and in Vienna. His only court appointment under Emperor Joseph II was as a composer of court dance music, a position that, in his words, paid him too much for what he did and not enough for what he could have done. The dance music includes German dances, Ländler and contredanses—popular forms of the time.

Concertos

Mozart wrote some 30 keyboard concertos. The earliest of these are four arrangements of movements by various composers, made in 1767. In 1772 he arranged three sonatas by the youngest son of J.S. Bach, Johann Christian, although these three works are not generally included in the numbering of the concertos. Apart from these arrangements he wrote six keyboard concertos during his years in Salzburg. The more important compositions in this form, designed clearly for the fortepiano (an instrument smaller than the modern pianoforte and with a more delicately incisive tone), were written in Vienna between 1782 and 1791. They were principally for the composer’s use in subscription concerts with which he at first won success in the imperial capital. Of the 27 numbered concertos, particular mention may be made of No. 20 in D minor, K. 466, and No. 24 in C minor, K. 491. He completed his last piano concerto—No. 27, K. 595 in B flat major—in January 1791.

Mozart wrote a series of five concertos for solo violin, one in 1773 and four in 1775, at a time when he was concertmaster of the court orchestra in Salzburg. Of the last four, K. 216 in G major, K. 218 in D major and K. 219 in A major are the best known, together with the splendid Sinfonia concertante of 1779 for solo violin and solo viola. The Concertone for two solo violins, written in 1774, is less frequently heard.

Mozart’s concertos for solo wind instruments include one for bassoon, two for flute, one for oboe, and one for clarinet—his final concerto, written in October 1791. He wrote four concertos for French horn, principally for the use of his friend, the horn player Ignaz Leutgeb, and a Sinfonia concertante for solo wind instruments, designed for performance by Mannheim friends in Paris. During his stay in France in 1778 he also wrote a fine concerto for flute and harp, intended for unappreciative aristocratic patrons there.

Chamber Music

It was inevitable that Mozart should also show his mastery in music for smaller groups of instruments. With some reluctance he accepted a commission in Mannheim for a series of quartets for flute and string trio, two of which he completed during his stay there in 1777–8. A third flute quartet was completed in Vienna in 1787, preceded by an oboe quartet in Munich in 1781; a quintet the following year for French horn, violin, two violas and cello; and finally, in 1789, a clarinet quintet. The wind part of this last work was for Mozart’s friend Anton Stadler, a virtuoso performer on the newly developed clarinet and on the basset-clarinet, an instrument of extended range and of his own invention.

Mozart’s work for string instruments includes a group of string quintets written in Vienna in 1787, and, over the course of around 20 years, some 23 string quartets. Particularly interesting are the later quartets, a group of six dedicated to and influenced by Joseph Haydn, and three final quartets, the so-called ‘Prussian’ Quartets, intended for the cello-playing King of Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm II. Ein musikalische Spass (‘A Musical Joke’), K. 522, for two horns and solo strings, was written in 1787; the music is a recreation of a work played for and presumably composed by village musicians, including formal solecisms and other deliberate mistakes of structure and harmony.

There are other chamber-music compositions, principally written during the last 10 years of Mozart’s life in Vienna and involving the use of the piano, an instrument on which Mozart excelled. These later compositions include six completed piano trios, two piano quartets, and a work that Mozart himself considered his best: a quintet for piano, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and French horn, K. 452.

Mozart added considerably to the repertoire of sonatas for violin and piano, writing his first between the ages of six and eight, and his last in 1788, making up a total of some 30 compositions. On the whole, the later sonatas intended for professional players of a high order have more to offer than the sonatas written for pupils or amateurs, although there is fine music, for example, in the set of six sonatas written during the composer’s journey to Mannheim and Paris in 1777 and 1778.

Piano Music

Mozart’s sonatas for the fortepiano cover a period from 1766 to 1791, with a significant number of mature sonatas written during the years in Vienna. The sonatas include much fine music, ranging from the slighter C major Sonata for beginners, K. 545, to the superb and more technically challenging B flat Sonata, K. 570. In addition to his sonatas he wrote a number of sets of variations, while his ephemeral improvisations in similar form are inevitably lost to us. The published works include operatic variations as well as a set of variations on the theme Ah, vous dirai-je, maman, known in English as ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’.

Organ Music

There is very little organ music by Mozart or, indeed, by other great composers of the period, although organ improvisation was an art generally practised, then as now. Mozart’s organ music includes a few compositions for mechanical organ, one improvisation (transcribed from memory by a priest who heard most of it), and a number of smaller compositions perhaps intended for organ but written in childhood. Mozart’s last appointment in Salzburg was as court organist, and there are significant organ parts in some of the church sonatas he wrote during that brief period, in 1779 and 1780.